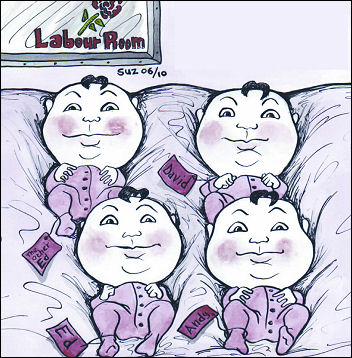

Cloning New Labour

The next leader of

Britain’s main ‘opposition’ party will be one of four New Labour clones.

None of them offers any alternative to the millions of people about to

suffer savage attacks by the Con-Dem coalition. Despite claims by some

on the left, the idea that the Labour Party could now be reclaimed by

working-class activists is a forlorn hope. HANNAH SELL reports on the

leadership contest and why the need for a new mass workers’ party is

ever more urgent.

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST

public-sector cuts will overshadow all other issues in the coming months

and years. Building a movement powerful enough to defeat the cuts will

be the first task on the agenda of the workers’ movement. For some, the

question of achieving political representation for the working class may

be relegated to a problem for a later day. In reality, however, creating

a political force which stands firmly against the cuts is a crucial part

of the battle to defeat the axe men.

The Trade Unionist and

Socialist Coalition (TUSC) – involving the Socialist Party, other

socialists and, crucially, an important layer of militant trade

unionists – stood in 41 seats in the general election in order to

prepare the ground for the development of a mass independent party of

the working class. As we expected, the pressure many workers felt to

vote Labour to try and stop the Tories meant that the political support

and sympathy TUSC received was not reflected in its vote. However, over

the next period, we believe that TUSC can come into its own and can act

as a catalyst for the development of a new mass party of the working

class. It is to be welcomed that, since the general election, all

participants in TUSC have agreed to continue and to make plans to stand

the widest possible slate of candidates in next year’s local, Scottish

parliament and Welsh assembly elections.

An important role for

socialists in the coming movement will be to promote TUSC as widely as

possible. However, it is also necessary to examine the arguments of

those who believe that independent workers’ representation will be

achieved by other means. New Labour’s ejection from power has raised the

hope, albeit faintly, that it may be possible to reclaim it for the

working class. This would mean changing New Labour back from the

capitalist party it is today into ‘old’ Labour, a party which, while it

had a capitalist leadership, was a workers’ party at its base and could

be pressured by the working class via its democratic structures.

The obstacles to reclaiming

Labour are enormous. New Labour is a shell of a party, with no

democratic structures at national level. The difficulties with

reclaiming it were thrown into sharp relief by the recent leadership

campaign of the left-wing MP, John McDonnell.

John McDonnell is widely

recognised in the trade union movement as the MP who has done most to

campaign in parliament in support of workers’ demands. That is why he

received a standing ovation at the PCS civil service union conference

this year, where he announced his intention to stand for the Labour

leadership, and why the Labour-affiliated Unite union conference,

against the recommendation of its executive, correctly passed a motion

calling for Unite-sponsored MPs to nominate John McDonnell.

Despite this widespread

support, however, John McDonnell has not even been able to take part in

the leadership contest. New Labour’s undemocratic constitution means

that the support of a conference representing 1.6 million trade

unionists is not enough to get on the ballot paper, it is also necessary

to have the support of 12.5% of Labour MPs. This was originally

increased from 5% to try and stop Tony Benn standing in 1988, as the

right-wing grip on the Labour Party increased. Today, the overwhelmingly

right-wing, pro-capitalist nature of the parliamentary Labour Party

meant that John McDonnell never had a chance of getting on the ballot

paper.

What’s left?

SOME MAY SUGGEST that this is

an unduly negative view given that Diane Abbot, a member of the

Socialist Campaign Group who nominated John McDonnell in 2007, scraped

into the contest. Unfortunately, this is both a sign of the weakness of

the left in New Labour and of Diane Abbott herself, not their strengths.

MPs from New Labour’s rightwing – including David Miliband, Jack Straw,

Phil Woolas and Stephen Twigg – felt able to nominate her in order to

demonstrate the party’s diversity, without fearing the consequences.

Diane Abbott is not a New

Labour clone like the other candidates – David and Ed Miliband, Ed Balls

and Andy Burnham – and when she has appeared in debates she has been to

the left of the others, but not by much. As one witness at the

leadership debate at the Compass 2010 conference, an Abbott supporter,

sadly put it: "She put in a pretty woolly performance, failing to land

any killer blows". (Labour Briefing, June) When she appeared on BBC’s

Newsnight leadership candidates debate, she did not even oppose

public-sector cuts unequivocally. Extremely timidly, she went no further

than saying: "Well, I certainly think that before we cut peoples’ jobs

and cut peoples’ public services we should look at things like a wealth

tax". She added that she would cut spending on the Trident nuclear

weapons system and save money by having a "staged withdrawal" from

Afghanistan.

Abbott even praised former

prime minister, Gordon Brown, for doing a "great job at the start of the

economic crisis". She did not say a word about how Brown bailed out the

banking system at the expense of the taxpayer, while leaving the banks

under the control of the ‘banksters’ who wrecked it in the first place.

Nor has she featured the

question of the anti-trade union laws in her campaign, despite this

being a critical issue for trade unionists. That a campaign of the kind

that Diane Abbott is running could be considered to be on the left at

all is an indication of how far New Labour is removed from the Labour

Party of the past. Even the 1987 Labour election manifesto, at the time

the most right-wing since 1945, written by the right-wing, witch-hunting

leadership, pledged to introduce a wealth tax on the richest 1%. Today,

Abbott only dares to suggest that it should be ‘looked at’.

It is completely utopian to

imagine that the current, extremely enfeebled, Labour left could ever

wrest the party back from the capitalists. It would require new forces

entering the scene on a large scale for there to be any chance of a

serious struggle to reclaim the party. Len McCluskey, who is standing

for the position of general secretary of Britain’s biggest trade union,

Unite, declared that "

has promised that he will lead a

serious campaign to reclaim the party.

Funding New Labour

UNITE LEADERS HAVE promised

this before, however. When Tony Woodley first stood as general secretary

of the TGWU (now part of Unite) he said that he would "campaign to put

the Labour back in the party". He would "call a summit of affiliated

trade unions to discuss how to get Labour back representing

working-class people" (The Guardian, 2 June 2003). These promises,

however, came to nothing. Two years later, Unite supported the 2005

Labour election manifesto which made no promise to repeal the anti-trade

union laws, further extended privatisation of public services, and

supported the continuation of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

However, if Len McCluskey

were to launch a serious campaign to reclaim Labour it would be a

thousand times more effective than the efforts of the Labour left alone.

For starters, Unite is a major financial contributor to New Labour. In

the nine months before the general election, it gave £3.318 million, 30%

of all the funding the Labour Party received. In total, the unions were

responsible for 61% of all donations to Labour over the same period of

time.

Unfortunately, the size of

union donations to New Labour bears no resemblance to their power or

influence within the party. The increased proportion of New Labour’s

funding which comes from the unions is purely due to the fall in

big-business funding. It is not because the party has moved left but

because it has become less electorally successful as a result of

following pro-big business policies!

During New Labour’s ‘glory

years’, big-business donations poured in as the capitalists rightly

recognised New Labour as the best party to govern in their interests. In

1999, for example, trade union donations fell to just 30% of New

Labour’s total funds. Slavishly following the interests of capitalism

and the City eventually led to a collapse in New Labour’s popular

support. Tossing it aside like a used plaything, big-business funding

then switched from New Labour to the Tories. Nonetheless, big business

still calls the tune.

A comparison can be drawn

with the US Democrats – which has always been a capitalist party. Unlike

the situation in Britain, US unions have no formal links with the

Democrats but there is a long history of the labour movement giving

support to Democratic candidates – as was also the case with the Liberal

Party in Britain prior to the creation of the Labour Party. In the last

US presidential election, for example, the AFL-CIO union federation set

aside a budget of $53 million to support the Democrats. But this

financial support does not give the US labour movement any influence

over Democratic policy.

The end of party democracy

FUNDAMENTALLY, THE SAME is

true of the union movement’s relationship to New Labour in Britain. The

raft of rule changes introduced in 2007 – the latest in a long series –

removed the last vestiges of democracy from the party. When it was

founded over a century ago, the Labour Party was the first political

party in Britain to have a democratic annual conference which was the

sovereign body of the party. This has now been so utterly destroyed that

one constituency delegate at last year’s conference complained that,

despite the fact that he and other delegates had "shown the party

officers our pre-written speeches and accepted their corrections, [we]

were still not called". (Labour Briefing, November 2009)

The process of fundamentally

undermining the democratic structures of the Labour Party was given

impetus with John Smith’s introduction of One Member One Vote (OMOV).

This was a means of using the more passive members – those sitting at

home and seeing debates within the party via the capitalist media –

against the more active layers who participated in the democratic

structures of the party.

At the same time, the union

block vote at conference was reduced from 70% to 50%. The organised

working class was able to pressurise the Labour leadership via the block

vote. It is true, of course, that right-wing trade union leaders often

wielded the block vote against their own members’ interests. This is why

Militant, the predecessor of the Socialist Party, called for democratic

trade union checks over the block vote as part of our programme for

democratic, fighting trade unions. Nonetheless, the reduction of the

block vote was an essential part of transforming Labour into a

capitalist party.

Tony Blair then went further

and completely stripped the Labour conference of its power. It became

merely a consultative body. If that was not enough, Brown went further

again, implementing a system where each union could only move one

‘motion’ at the conference – of ten words or less! This could not be on

any issue already covered by the National Policy Forum. The ten words

cannot be agreed by the conference but have to be sent back to the

National Policy Forum for ratification or otherwise. The National Policy

Forum was, until last year’s conference, made up of handpicked

constituency and parliamentary representatives, with only one sixth of

its members coming from the trade unions. It is hard to imagine a more

Kafkaesque negation of democracy.

At the 2009 conference, the

Labour left claimed a tiny victory against the leadership when it got a

rule change passed introducing OMOV for the election of constituency

representatives to the policy forums. Workers’ democracy has been so far

removed from New Labour that, today, the very measure that the rightwing

used to gain an iron grip on the party is now seen as a step forward!

A campaign to reclaim Labour?

THESE UTTERLY UNDEMOCRATIC

structures could never be used by Unite to reclaim Labour. New,

democratic structures would have to be rebuilt from scratch. Far better

for the trade unions to disaffiliate and to use the money to begin to

build a party that actually stands in the interests of its members.

Nonetheless, a serious campaign to reclaim Labour would be infinitely

preferable to the current strategy of most trade union leaders of

clinging to New Labour politicians’ coat-tails – after paying for the

coat!

A serious campaign would have

to combine rebuilding democratic structures with the demand that Labour

adopts a socialist programme. Key demands would include the repeal of

all the anti-trade union laws and opposition to all cuts in public

services, not just in words but in action. Up and down the country, New

Labour councils are going to be implementing the government’s massive

cutbacks ‘under protest’.

Len McCluskey rightly defends

the struggle of Liverpool city council in the 1980s. Part of the

struggle to reclaim Labour would be to demand that New Labour councils

refuse to implement cuts, mobilising the workforce and population in a

mass campaign in their support. Such a campaign of defiance by Labour

councils could quickly bring down the Tory/Liberal government. It would

also be necessary to demand that the pro-capitalist and pro-war

Blairites and Brownites be ejected from the party.

If such a campaign succeeded,

Marxists would have to re-evaluate the situation and change our

orientation accordingly. Equally, if such a campaign failed, McCluskey

and others would have to draw the conclusion that a new party was the

only way forward. We think that this would be the outcome of the

experiment. To successfully reclaim Labour would mean organising tens of

thousands of trade unionists – not just to join New Labour passively but

to fight tooth and nail to rebuild it from the ground up.

Shifting attitudes to New Labour

SOME HOPE THAT this may

happen as a result of workers looking at the Con-Dem government and

concluding that there is no choice but to return to the ‘safety’ of

Labour. This will not work. Firstly, because the memories of the crimes

of New Labour are so fresh. At the end of New Labour’s 13 years in

power, the gap between rich and poor was at its highest point for 70

years. The anti-trade union laws were not only intact, they were being

used in the harshest way against workers taking strike action. Hundreds

of soldiers had died in the brutal occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan.

Free university education had been abolished. Any worker under 40 has

only experienced Labour as the brutal capitalist party responsible for

these policies.

And even now, in opposition,

New Labour, as would be the case with any capitalist party, is not

really opposing massive public-service cuts. It just suggests that they

should be started a bit more slowly. If New Labour had been re-elected

it would also have decimated public services. In many areas, Labour

councils had already begun vicious cuts under the previous government.

Kirklees in Yorkshire is just one example. There, £400 million is being

cut from council spending over four years, resulting in 2,000 job losses

and the first local authority compulsory redundancies. Now the pace of

cuts will accelerate dramatically with New Labour councils carrying out

the government’s programme.

If they were to refuse to do

so, this would create a pole of attraction for mass struggle. Far more

likely, unfortunately, like the Labour councils that jailed poll tax

non-payers while weeping about the iniquity of the tax, we will see them

doing the government’s dirty work. They will use the argument of the

‘dented shield’ that Labour councils used in the 1980s: that it is

better, at least, for a ‘friendly hand’ to wield the knife. This will be

less effective even than it was then, however, both because of the depth

of the cuts – the worst since the 1920s – and because of the memory of

New Labour in office.

This does not mean that there

will not be any workers who join the Labour Party. However, the numbers

that Labour report having joined since the general election – estimates

between 13-20,000, many of whom are, reportedly, ex-Liberal Democrats –

are a drop in the ocean compared to the 150,000 plus who left New Labour

while it was in power. And, of those who have joined, few will attend

more than one moribund local party meeting, if they can find one to

attend at all.

There will be a continuation

of the trend seen in the general election, with significant sections of

workers voting Labour through gritted teeth in order to stop the Tories,

in the belief that the cuts would have been less severe under a Labour

government. This mood can strengthen as the government’s cuts start to

bite and a certain rose-tinted view of New Labour in power develops

among some workers. However, this does not mean that large numbers of

workers will join the Labour Party, or see it as means to struggle

against the cuts.

This has not been the

experience in other European countries when the ex-social democratic

parties have lost power. In countries as varied as Sweden, France,

Greece and Germany these parties have remained empty shells when thrown

out of office. They have sometimes gained electorally at a certain

stage, as the ‘lesser evil’, but this has not led to a rejuvenation of

the party. PASOK in Greece, for example, was elected with a large

majority. Just months later, it is facing an uprising of the working

class in opposition to the brutal cuts it is carrying out.

Significantly, however, SYRIZA – the new left formation in Greece – came

into being and reached 18% in the opinion polls while New Democracy, the

equivalent of the Tories, was still in power. The fact that it has since

sunk in the opinion polls has nothing to do with PASOK’s popularity, and

everything to do with the failure of the SYRIZA leadership, at least up

until now, to sufficiently differentiate itself from PASOK with a clear,

fighting, socialist programme.

Break the union-Labour link

THE ATTITUDE OF workers in

Britain to New Labour will be fundamentally the same as was the case in

Greece when PASOK was out of power, giving similar opportunities for new

formations to develop. This is very different to what happened in the

1970s and early 1980s. When Labour was thrown out of power in 1979 a

strong leftward move developed in the ranks of the Labour Party. This

culminated, in 1981, with Tony Benn losing the deputy leadership

election by less than 1%. However, this process had already begun over

the previous decade. While Labour was still in office there was already

a strong left wing which opposed the government’s regressive policies.

It was at the Labour Party conference in 1978 that a Militant supporter

successfully moved a motion rejecting the ‘5% limit’ that the government

had imposed on workers’ wages. This opened the floodgates to the

industrial movement now known as the winter of discontent.

All kinds of other radical

motions gained an echo at the conference, including the demand for the

reselection of MPs, which was finally won in 1981. At that stage, the

increased militancy of the working class, and anger at the capitalist

policies of the Labour government, found a strong echo within the Labour

Party.

That has simply not been the

case during New Labour’s rule over the last 13 years. On the contrary,

whenever workers have moved into struggle, particularly against the

government, the call to break the link with New Labour has grown

dramatically. The fire-fighters’ strike of 2002 led directly to the FBU

breaking the link. One result of the postal workers’ strike was that, in

2009, in a referendum of London CWU members an astounding 98% voted to

break the link. If a similar referendum had been carried out in other

regions, there is no doubt that a majority would have also voted in

favour of disaffiliation.

In addition, within the

affiliated trade unions, increasing numbers of members do not give

permission for part of their dues to be paid to the Labour Party via the

affiliated political funds. As a result, whereas the Labour-supporting

trade unions paid affiliation fees for 3.2 million members in 1997, this

had fallen to 2.5 million in 2006. In the local authority and health

union, Unison, only 32% of members now pay into the Labour Link fund.

The proportion of new members is even lower, at 27%. Many of those

paying into the affiliated fund do so out of historical inertia, rather

than support for Labour. In the 2007 Labour deputy leadership contest,

only 8% of affiliated members voted – and almost a sixth of the ballots

were spoiled because voting members had not ticked the required box

saying that they agreed with Labour’s policies!

When trade union activists

appeal to workers to join Labour to fight to change it they are met with

blank stares, at best. By contrast, the appeal to break the link with

Labour and begin to build a new party gains enthusiastic support,

particularly among the most militant layers. This is shown by the recent

Unison general secretary election where Socialist Party member, Roger

Bannister, received 42,651 votes (19%), standing clearly to "stop

funding the Labour Party and to start to build a new trade union based

party".

This was the fourth

consecutive Unison general secretary election in which Roger has stood.

Unfortunately, in every one of these elections, the left vote was split.

Each time, the argument of those left activists who have refused to

support Roger is that his call to break the link with Labour is

unpopular. Each time, Roger has decisively beaten the other left

candidate. It is time that others drew the conclusion that it is the

Socialist Party’s programme which has the best chance of mobilising

rank-and-file Unison members to win political representation.

The struggle for workers’ representation

THE COUNTER ARGUMENT of

Labour lefts is twofold. Firstly, it is suggested that the failure to

create a new mass workers’ party over the last decade shows that it is a

futile goal. Secondly, that a new formation would split the Labour vote

and thereby condemn the working class to an eternity of Tory government.

Neither argument is new.

John Burns, one of the first

Labour MPs, condemned the Independent Labour Party’s 1895 general

election result, when Kier Hardie lost his seat, as "the most costly

funeral since Napoleon". (Origins of the Labour Party, Henry Pelling) He

did so because he still orientated towards the Liberals, which were seen

by most workers as the ‘lesser evil’ of the time. TUSC’s general

election result was met with similar prophecies of doom, although not

the hostile response from the public that the ILP sometimes got. In a

Barnsley by-election in 1897, the candidate was driven out of one

village by Liberal Party supporting miners in a hail of stones (Pelling).

TUSC, by contrast, received a very friendly response in the recent

general election.

Despite the considerable

difficulties faced by the forerunners of the Labour Party, the TUC

conference voted to found the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) just

four years after the 1895 general election. There were 129 delegates at

the 1900 conference to found the LRC, but they represented half a

million trade unionists. Even so, at that stage it was only a minority

of TUC-affiliated trade unions that sent delegates to the conference –

many were still tied to the Liberals. Some of those who attended then

hesitated and withdrew their affiliation. In the 1900 general election,

the LRC received a modest vote of 1.8%.

It was the effect of the Taff

Vale judgement – a vicious anti-trade union law – which made growing

numbers of trade unionists determined to create their own political

voice, independent of the Liberals. The affiliated membership of the LRC

grew from 375,000 at its foundation to 861,000 in 1903. All this

happened under a Tory government. In 1906, the Liberals were elected on

a landslide (their last!) and were forced to repeal the Taff Vale laws

as a result of the pressure of the LRC, which had had 29 MPs elected.

Foundations of a new party

THERE ARE MANY lessons that

can be drawn for today, but the most important is that it will be as a

result of their experience in struggle that workers conclude that they

need to build their own party. There are many other examples that could

be given. In the 1992 general election, Tommy Sheridan stood in Glasgow

Pollok as Scottish Militant Labour (then the name of our sister

organisation in Scotland). He had never stood in a general election

before and yet received 6,287 votes, 18% of the total. He achieved this

not by a fluke but because he was a leader of the 18 million-strong

anti-poll tax movement (in prison at the time for his role), which had

brought down the Iron Lady, Margaret Thatcher. Had we stood candidates

in England and Wales during the anti-poll tax movement, there is no

doubt we could have had similar successes.

Last year, Joe Higgins, a

member of our sister section in Ireland, gave another glimpse of what is

possible when he was elected as a Socialist Party member of the European

parliament (MEP) for Dublin – receiving over 50,000 first-preference

votes. Again, it was Joe and the Socialist Party in Ireland’s record in

struggle – defeating the threat of water charges, fighting the bin tax

(for which Joe was sent to prison), involvement in countless workers’

struggles, like the GAMA dispute (where Turkish migrant workers won a

brilliant victory) – which was crucial to the election victory.

The same can be said, on a

smaller scale, of the councillors that the Socialist Party has been able

to win in England and Wales. Even this year, when we lost council seats

– as a result of the increased turnout caused by the local elections

coinciding with the general election and workers’ fear of a Tory

government – the votes our councillors received were the highest ever as

thousands of workers tried to make sure that, at least, they had proven

fighters representing them at local level. We are confident that our

record in struggle will mean that we can retake the seats that we have

temporarily vacated.

The profound crisis of

capitalism and the unprecedented attacks that are going to rain down on

the public sector will mean that the working class in Britain will have

no choice but to struggle. Socialists will have a very important role in

putting forward a strategy that can unify all of those under attack –

public-sector workers and service users, young and old, the unemployed

and workers – around a programme against all cuts. A mass demonstration

will need to be quickly followed by a 24-hour general strike – probably

of the public sector, initially. Events on this scale will lead to a

profound alteration in the consciousness of those who participate. That,

combined with the brutal, crisis-ridden nature of capitalism, will lead

many thousands to draw socialist conclusions.

This does not mean that there

will not be complications, a legacy of the confused consciousness of the

last decades. The far-right BNP can make further gains, especially

electorally. Another layer may temporarily think ‘to hell with politics’

and concentrate on the industrial struggle alone. Nonetheless, there

will be a growing demand for workers to have their own anti-cuts,

socialist candidates. TUSC can play a crucial role as an instrument for

the creation of a mass party of the working class.