|

|

Issue 180 July/August 2014

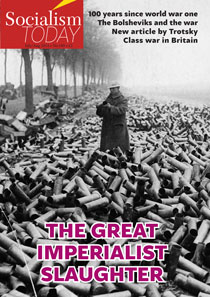

One hundred years since the great slaughter One hundred years since the great slaughter

The first world war began 100 years ago,

unleashing slaughter on an unprecedented scale. This anniversary has

featured prominently in the capitalist media. Most fail, however, to

explain why millions of working-class people were sent to their deaths

in trench-warfare hellholes: capitalism’s drive for profit,

exploitation, raw materials and markets. TONY SAUNOIS writes.

It was dubbed the ‘Great War’, the ‘war to end

wars’. For the ten million killed and more than ten million seriously

injured it was certainly not great. The battles fought saw some of the

bloodiest human slaughter in history. The ineffable misery and losses

suffered on both sides are only surpassed by the scale of these

gargantuan events. At Ypres, Belgium, the British army lost a staggering

13,000 men in three hours only to advance 100 yards! In the first day of

the Battle of the Somme it took 60,000 casualties, the greatest loss

ever suffered by the British army. This was in spite of the fact that in

the preceding six days German lines had been hit by three million

shells!

Total casualties in the Battle of the Somme were 1.1

million men on both sides. By 1918, the Entente powers (led by Britain,

France, Russia and Italy) counted 5.4 million dead and seven million

wounded. The opposing Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the

Ottoman empire and Bulgaria) suffered four million deaths, 8.3 million

wounded. Young working-class conscripts bore the brunt of these losses.

As subsequent conflicts have erupted around the

planet, it is self-evident that it did not mean an end to war. In the

current carnage in Syria, 6.5 million people have been internally

displaced and a further three million driven into external exile. Human

suffering and killing have been repeated again and again since this ‘war

to end war’.

Yet the bloodbath that erupted between 1914-18 has

possibly evoked the most comment and analysis. According to one

estimate, at least 25,000 books have been published on the subject. It

was, after all, the first truly global conflict. It ended one historical

era, opened another, and reshaped international and class relations. In

its wake, empires collapsed, some rapidly, while others took a slower,

more inglorious decline. It opened the way for the USA to replace

Britain as the world’s leading imperialist power. Above all, it acted as

the midwife to the greatest event in human history: the Russian

revolution in 1917. There, the working class was able to take over the

running of society. At the same time, a revolutionary wave engulfed most

of Europe.

The prospect of a socialist revolution in a series

of European countries was posed. In Germany 1918-19, the kaiser was

forced to abdicate as a workers’ revolution swept the country. In

Bavaria, a soviet republic was declared, and workers’ councils

established in Berlin and other cities. In Hungary, a soviet republic

was briefly established between March and August 1919. Mass strikes and

over 50 recorded military/naval mutinies took place in Britain. A police

strike in 1919 compelled the prime minister, David Lloyd George, to

admit years later: "This country was nearer to Bolshevism that day than

at any time since". However, with the exception of the Russian

revolution, these mass movements were ultimately defeated by the

mistaken polices adopted by the workers’ leaders. The defeat of the

revolutions in Europe sowed the seeds of the second great global

conflict, 1939-45, so that can also be traced to the legacy left by the

carnage of 1914-18.

The approaching war in 1914 posed a decisive test

for the international workers’ movement. Excepting a tiny minority –

including Lenin, Trotsky and the Russian revolutionaries, Karl

Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in Germany, and a handful of others – the

leadership of powerful mass workers’ parties capitulated one after

another. They abandoned an internationalist socialist anti-war position,

and backed their respective ruling classes.

No wonder that this great tragedy of human history

has provoked such comment and analysis. Indeed, even a century after the

conflict began, capitalist historians like Niall Ferguson and Max

Hastings continue to debate its causes and offer their own analysis and

conclusions. All capitalist apologists and commentators find great

difficulty in justifying the war. They justify the conflict in 1939-45

as a war against fascism and for democracy. Not so, the mass slaughter

of 1914-18.

The struggle for markets

The trigger for the carnage was the assassination of

the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Yet could

this really be the cause of such a global conflict? Although centred in

Europe, the war drew in Africa, Asia, Latin America and, of course, the

USA. While the shooting of the archduke may have been the excuse to

unleash the dogs of war, the real underlying causes lay elsewhere. The

war erupted as a massive struggle in defence of economic interests,

markets and political power and prestige.

In the period up to 1914, Britain was the dominant

global power with a vast empire covering 25% of the earth’s surface.

Most of the countries it ruled had been colonised prior to the mid-19th

century. The empire was a source of raw materials and markets. However,

Britain’s economic growth was slowing. It was a declining power. France,

the other major European power at the time, had an empire mainly centred

in Africa and the Far East. Although substantial, its empire was only

about one fifth the size of Britain’s, and its industrialisation lagged

far behind.

Germany, only unified in 1871, had colonies only

about one third the size of those of France. Nonetheless, it had

experienced rapid industrialisation and economic development. Its

economy was more productive than Britain’s. While Britain was producing

six million tons of steel, Germany produced twelve million. However, it

was in desperate need of more colonies to supply it with raw materials

and much larger markets – the logic of capitalist economic development.

The problem was how to secure them. There was nowhere to expand to in

Europe, and Britain and France had the lion’s share of the colonies. To

the east, Germany was blocked by an expanding tsarist Russian empire and

Anglo-French interests in eastern Europe.

This struggle for markets lay at the root of the

great conflagration which was to erupt in 1914. The development of the

productive forces – industry, science and technique – had outgrown the

limitations imposed by the nation state. It drove the imperial powers to

conquer and exploit new colonies in the hunt for raw materials and new

markets. This had already brought Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal and

Germany into conflict in the so-called ‘scramble for Africa’ during the

19th century. Eventually, this competitive struggle brought the main

imperial powers into horrific conflict, as each tried to secure bigger

markets or to defend those threatened by emerging powers. If new markets

cannot be found, capitalism is driven to a destruction of value in order

to begin the productive process anew. The price was to be paid by the

working classes of all countries in this power struggle.

Some argued that this contradiction of capitalism

had been overcome when it seemed, like today, that a major globalisation

of the world economy had taken place. In the four decades following the

Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, there was a period of substantial

economic growth and expansion. The world economy had become more

interdependent. Between 1870-1914, there had been a significant and

until then unprecedented economic globalisation and integration. This

has some comparisons to the situation which has developed in the recent

period, especially since the collapse of the former Stalinist states in

Russia and eastern Europe.

The globalisation of recent decades has gone further

than ever before, but those who argue that there was not an analogous

development before the first world war are wrong. And, like today, in

1914 it did not mean that the nation state or the national interests of

the ruling classes had become obsolete, or a decorative remnant of a

previous historical period of capitalism – as the 1914-18 war

graphically demonstrated. Then, as now, despite a dominant, integrated

global economy, the ruling classes of the different countries still

maintained their own vested historic, economic, political, military and

strategic interests. Recent imperialist interventions and local or

regional military conflicts have also revealed how each ruling class

will act to defend its own specific economic, political and strategic

interests where it can.

Impending disaster

In addition to the underlying cause of the ‘great

war’ – the scramble for colonies and markets – other interconnected

historical factors played an important role in the drive to defend the

interests of the ruling classes of Germany, France, Britain and tsarist

Russia. The Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 resulted in the establishment

of a unified Germany and opened the road to its rapid economic

development and expansion. France was left weakened. The outcome of this

conflict, along with others, left a legacy which was picked up in 1914.

Karl Marx had commented on this as the Franco-Prussian war unfolded. The

consequences of the changed balance of forces would result, he

anticipated, "in war between Germany and Russia". In the same letter, he

commented that such a conflict would act as "the midwife to the

inevitable social revolution in Russia". (Letter to Friedrich Sorge, 1

September 1870) It may have been a lengthy propinquity but one of the

consequences of the 1870-71 war anticipated by Marx was born out

eventually in 1914.

A weakened France lost part of its territory,

Alsace-Lorraine, and was compelled to pay large war reparations to

Germany. France was in no position to oppose Germany militarily by 1914,

with half the population and far inferior military hardware. The

Tangier’s crisis in 1905 and the Agadir crisis in 1911 both pointed to a

conflict with Germany as it continued to oppose French colonial

expansion.

The outbreak of the Balkan war in 1912 was a crucial

step towards the 1914-18 war. At this juncture it was anticipated that

there was a threat of war across Europe. On 8 December 1912, the German

Kaiser Wilhelm II convened the Imperial War Council in Berlin. Most of

the participants agreed that war was inevitable at some stage, but it

was delayed to allow a strengthening of the German navy. Nothing was

concluded at this council but it was clear that war was being prepared

for. In fact, the end of the 19th century up until 1914 was marked by a

massive arms build-up by all the European powers.

It was also clear for the international workers’

movement. In November 1912, over 500 delegates from the Second

(‘Socialist’) International met in Basel. They agreed a resolution

opposing the Balkan war and the threat of war across Europe in favour of

international working-class struggle. Scandalously, one by one the

social-democratic party leaders capitulated and supported their own

capitalist classes in the conflict.

The collapsing Austro-Hungarian empire was compelled

to act against Serbian attempts to expand in the Balkans as allowing

this to go unchallenged would have weakened it still further. The

outbreak of the 1912 Balkan war was a crucial element in the conflict.

Tsarist Russia lent support to Serbia in order to extend its own

interests in the region. Germany was compelled to encourage Austria.

Thus, when Russia ordered a full military mobilisation in response to

Austria-Hungary declaring war on Serbia on 28 July 1914, Germany

responded by declaring war on Russia and France (1-3 August 1914). When

Germany invaded Belgium in order to march on France, Britain declared

war on Germany.

The outbreak of war

Economic expansion had dominated the 40 years

leading up to the war. In 1913 strikes and protests had broken out in

all the main countries as workers demanded their share of the growth.

The German workers’ party, the SPD, had made important gains in the

elections of 1912. At the same time, 1913 saw an abrupt change with the

onset of an economic crisis. The ruling classes were worried that a

further intensification of the class struggle would develop. The threat

of war was used in all countries to try and cut across this.

The nationalistic propaganda on each side inevitably

resulted in a huge patriotic wave at the outbreak of the war. All

governments claimed, as is always the case, that the war was a just

cause and would be over quickly. In Germany, the slogan was, ‘home

before the leaves fall’; in Britain, ‘it’ll all be over by Christmas’.

Behind the scenes, the ruling class had a more realistic assessment of

the situation. Sir Edward Grey, British foreign secretary, commented:

"The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit

again in our lifetime".

There were anti-war demonstrations in most

countries. In Germany, hundreds of thousands took part in peace

protests. Many ‘conscientious objectors’ heroically held out in

opposition. However, the overwhelming mood at the outbreak of the war

was one of patriotic fever. The attitude to the conscientious objectors

was markedly different in 1914-18 compared to 1939-45. In the latter,

the conflict was seen in Britain as a ‘war against fascism’ and

objectors were viewed as cowards, not prepared to fight when ‘the enemy

is at the gate’. This was not the case in the first world war.

Recently, the historian Niall Ferguson has argued

that Britain should have stayed out of the war. He said that it would

have been better to allow Germany to dominate Europe. Britain, he

argues, would then have been in a stronger position to defend its

interests because it would not have used vast resources in fighting the

war. Like all of the powers, the war certainly cost British imperialism

dearly. It had financed most of the Entente’s war costs until 1916 – all

of Italy’s, and two-thirds of France and Russia’s. Gold reserves,

overseas investments and private credit ran out. Britain was compelled

to borrow $4 billion from the USA. According to one estimate, Britain

and its empire spent $47 billion financing the war, Germany around $45

billion.

Yet, how could British imperialism have stood aside

from the conflict and allowed its main rival to emerge in a potentially

far more powerful position to expand its empire? A victorious German

imperialism would have been much better placed, economically,

politically and strategically, to challenge British imperialist

interests. Moreover, war has its own momentum and logic, and puts the

prestige of capitalist and imperialist rulers on the line. This would

have been lost by what was the dominant imperial power at the time. At

best, not entering the war in 1914 would have postponed a conflict

between British and German imperialism. The abstract musings of Ferguson

are disconnected from the realities of the interests of the ruling

capitalist classes when confronted with the dynamics of such conflicts.

Other historians, such as Max Hastings, have a more realistic assessment

and conclude that the war was inevitable. That, in itself, is a crushing

condemnation of the capitalist system he supports.

Revolutionary wave

The patriotic wave gave way to massive opposition as

the realities of trench warfare were experienced by millions on both

sides of the conflict. Troops fraternised at Christmas 1914, playing

unofficial football matches. The great Russian revolution of 1917 was

the first decisive break as the slaughter dragged on and on. The coming

to power of the Bolsheviks ended the war on the eastern front and had a

crucial impact in building opposition to the war on both sides.

Following the revolution, mass strikes broke out in Germany in 1918.

This, together with the now seemingly futile

slaughter, had a decisive impact, transforming the outlook of millions,

especially the soldiers and naval ratings. Mutinies broke out in the

French and British armies. In France, troops on the western front were

ordered to begin a disastrous second Battle of the Aisne in northern

France. They were promised a decisive war-ending battle in 48 hours. The

assault failed and the mood of the troops changed overnight. Nearly half

of the French infantry divisions on the western front revolted, inspired

by the Russian revolution. Three thousand four hundred soldiers faced

court martial.

In August 1917, there was a mutiny aboard the German

battleship, Prinzregent Luitpold, stationed in the northern sea port of

Wilhelmshaven. Four hundred sailors went ashore and joined a protest

demanding an end to the war. The British daily newspaper, The

Independent, recently published a moving letter sent by a young German

naval rating, Albin KÖbis, to his parents: "I have been sentenced to

death today, September 11, 1917. Only myself and another comrade; the

others have been let off with 15 years’ imprisonment… I am a sacrifice

of the longing for peace, others are going to follow… I don't like dying

so young, but I will die with a curse on the German militarist state".

On 3 November 1918, the fleet mutinied at Kiel and hoisted the red flag,

triggering a revolutionary wave across Germany.

These events, above all the Russian revolution, were

decisive in finally bringing to an end to the, by now, hated war. Its

ending ushered in a revolutionary wave across Europe which terrified the

ruling classes. With the exception of Russia, however, these massive

movements did not result in the working class taking power and holding

it.

The end of the war ushered in a new world situation

and changed the balance of power between the imperialist powers. The

triumph of the Bolsheviks in Russia introduced an entirely new factor

for the capitalist classes to confront. Germany was obliged, by the

Treaty of Versailles, to pay massive war reparations following its

defeat – £22 billion at the time – which had a devastating impact on its

economy. The final instalment of £59 million was only paid in 2010 – 92

years after the end of the war! The failure of the German revolution and

mistaken policies of the German workers’ parties paved the way for the

triumph of the fascists and Hitler in 1933, leading to the outbreak of

war again in 1939. The consequences of the first world war also

accelerated the decline of British imperialism, opening the way for the

USA in the 1920s and after to become the dominant imperialist power.

The failure of the socialist revolution in Germany

and the rest of Europe also meant that revolutionary Russia was

isolated. Eventually, that would result in the degeneration of the

Russian revolution and the emergence of a bureaucratic Stalinist regime

in the former Soviet Union. Despite the monstrous distortion of

socialism this regime signified, together with the imposition of similar

regimes in eastern Europe following the second world war, it did hold

the key imperialist powers in check. They were glued together – and were

able, largely, to mask their differences – against a common enemy which

represented an alternative social system to capitalism, based on a

nationalised planned economy. This was in spite of the undemocratic,

bureaucratic and authoritarian methods of rule of the Stalinist regimes.

New wars

However, the collapse of these regimes and the

re-establishment of capitalism have reopened the old and new tensions

which exist between the capitalist powers. The globalisation of the

world economy, which has now reached an unprecedented level – even more

so than 1870-1914 – has once again starkly revealed how, under

capitalism, the productive forces have outgrown the existence of the

nation states. Nonetheless, the recent conflicts which have erupted

between the world powers have revealed that the nation state is still

not obsolete, as each ruling class vies to defend its own economic,

political, military and strategic interests. The growing tensions

between the USA and China in Asia, the crisis within the European Union,

the 1990s conflict in the Balkans, and the current clash between Ukraine

and Russia, are all indications of the clash between the various

imperialist and capitalist powers. At root, these are also part of a

struggle to acquire new spheres of influence and markets, as was the

case in the 1914-18 war.

Many of the new generation are asking whether this

means that another world war is a possibility. Although the USA remains

dominant, it is a declining power, as Britain was in the beginning of

the 20th century. Even so, it remains the largest of the world powers,

still far ahead of China and Japan. The other emerging powers of Russia,

India and Brazil remain far behind but strive to extend their influence

in their own areas. The weakened position of US imperialism has been

clearly demonstrated recently by its inability to intervene directly in

Syria or in the Russian/Ukraine conflict. The catastrophic consequences

of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 have made it far more complicated for

such military interventions to be undertaken by US and British

imperialism, or other powers.

As recent events have revealed, the prospect of

regional conflicts and wars is posed in this era of renewed capitalist

crisis and the struggle for limited markets and resources. However, the

balance of social and class forces prevents, in the short to medium

term, the outbreak of a world war such as developed in 1914-18 and again

in 1939-45. The consequences of such a conflict, with the existence of

nuclear weapons which would mean total destruction, together with the

ruling classes’ fear of the social upheavals and revolution which would

arise, act as a decisive check on the rulers of imperialism and

capitalism today.

The stark reality of the horrors of war, and the

misery and human suffering which have flowed from the disasters

unfolding in Syria, Iraq, Russia/Ukraine and other areas, indicate the

bloody and brutal consequences of capitalism in the modern era. If

capitalism and imperialism are not defeated, further, even more

horrific, conflicts will erupt in the future. The lessons of the

slaughter unleashed between 1914-18 need to be drawn by a new generation

of young people and workers. The need for mass independent workers’

parties which struggle for an internationalist socialist alternative to

capitalism, and which combat the patriotic nationalism of the ruling

classes, is as relevant today as it was in 1914 if future bloodbaths are

to be avoided. Only a socialist world, based on the democratic planning

of the economy, can offer an alternative to the struggle for markets and

economic interests which are the inevitable consequences of modern

capitalism, and the source of conflict. |