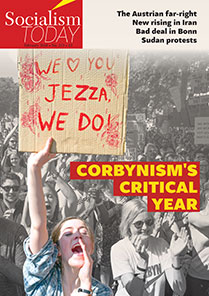

Corbynism’s

critical year

Corbynism’s

critical year

As Britain’s weak Tory

government clings on – and numerous social, political and economic

shocks threaten its downfall – a key factor is whether the Labour Party

can provide a mass alternative to harsh austerity. This is one of the

main themes in the British Perspectives document for the Socialist

Party’s national congress in March, drafted by HANNAH SELL, from which

we print edited extracts.

In the January 2017 British

Perspectives document we raised the possibility of Theresa May calling a

general election. We concluded: "Despite all of these reasons to avoid a

snap general election, it is not precluded that the Tories could be

forced to call one. If May faces deadlock in parliament over the

question of Brexit, in order to try and gain a more stable majority and

therefore room to manoeuvre, a general election may be her only way

forward". Particularly important among the reasons she should hesitate

to do so was our prediction that, "despite Labour’s current poll

ratings… it is not ruled out that – if Labour was to fight on a left

programme – it could win a general election". At that stage, we were

virtually alone in arguing that a Jeremy Corbyn-led Labour Party could

win.

In the event, of course, May

gambled and ‘lost’. She clung to power, but with her already thin

majority obliterated, only able to stay in government propped up by the

Democratic Unionist Party. Without doubt, the Tories’ incompetent

election campaign and May’s robotic performance were factors in the

result, but not the most important ones. The dynamic of the campaign was

transformed by Labour’s election manifesto which enthused millions of

people, particularly the young. Labour got over 40% of the vote compared

to just over 30% in 2015, the biggest increase in the vote share for any

party since Labour in 1945. Correctly, the Socialist Party did not stand

candidates as part of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition.

Instead, we campaigned for a Corbyn government with a socialist

programme.

There have been many positive

results from the general election. The government is rightly perceived

as extremely weak. Corbyn’s programme has reached much wider layers than

previously. For many young people it is the first time they have heard

the need for nationalisation being put forward and, since the election,

support for many of Corbyn’s policies has grown significantly. A Populus

poll in October 2017 found that big majorities support the

nationalisations put forward in his manifesto. Water topped the poll

(83%), followed by electricity (77%), gas (77%), and the railways (76%).

The same poll found that half of the population supports the

nationalisation of all major banks, which was not in the manifesto.

Despite the many positive

factors, the post-election landscape is complicated. Some very important

strikes and campaigns have taken and are taking place, particularly at

local level and on the railways. There have also been some significant

struggles of groups of precarious workers, including the magnificent

victory scored by the first McDonald’s strike in Britain. Overall,

however, the level of struggle is quite low. The potential for mass

movements on a wide range of issues is clear, given the obvious weakness

of the government and the enormous accumulated anger at austerity and

inequality. Nonetheless, the uneasy calm could continue for a period.

There are a number of reasons for this. Central is the role of the

majority of trade union leaders and also of the Labour leadership.

The right-wing union leaders,

who were determined to get rid of Corbyn just months ago, are resigned,

for the moment, to his continued leadership for a period. They are quite

happy to lean on and stoke a certain mood of ‘waiting for a Labour

government to save us’ in order to avoid organising a serious national

struggle against continued pay restraint and austerity. There is nothing

fundamentally new in their approach but, ironically, the increased hopes

of a section of workers in Corbyn make it easier than with the previous

Labour leader, Ed Miliband.

At the same time, the whole

preceding period – where the TUC leadership organised a successful

public-sector general strike in 2011 but then stepped back from leading

a serious struggle against Tory austerity – has left the majority of

trade union leaders extremely passive. They treat the crumbs that the

government has been forced under pressure to give on pay not as a sign

of weakness, showing the possibility of smashing the pay cap, but as

gifts to be met with gratitude.

The character of Corbynism

The Labour leaders also bear

responsibility for the complications in the situation. At root, their

limitations stem from their reformist outlook, believing that their task

is to win gains for the working class within the constraints of the

existing capitalist framework. Their hope, shared by millions, is that

they can win a parliamentary majority at the next election. In order to

achieve this, they have concluded that it is necessary to compromise

with the pro-capitalist wing of the Labour Party. This is a fundamental

error. Meanwhile, the right wing has been forced to appear reconciled to

Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. Yet, behind the scenes, it continues to work

to push him to the right and to take whatever opportunities arise to

undermine him.

Despite the limitations of

Corbyn’s programme, his most radical statements horrify the capitalist

class and their representatives in the Labour Party. Not least, they

fear Corbyn’s record of activism. He should not have given an inch to

that fear. Had he used his platform as Labour leader to call for serious

movements against austerity and its effects the government could have

collapsed by now, with Corbyn swept in on the back of mass mobilisation.

To give just one example: the mood of raw class anger that followed the

Grenfell Tower disaster.

At the time, Corbyn rightly

called for the requisitioning of the empty properties of the rich to

house the homeless. Six months on and more than 100 Grenfell families

have yet to be rehoused and the properties of the rich remain empty

assets on their property portfolios. Had Corbyn spoken to mass meetings

in North Kensington putting this forward, the class anger would have

been transformed into a movement on housing centred on the borough but

with a London-wide or even national scope.

This is not the only time

that Corbyn has been silent on the need for workers and young people to

get organised in defence of their interests. It is undoubtedly a factor

in the electoral ‘youthquake’ not yet having been transformed into a

movement for free education, despite the clear potential for it. Nor has

he called for national action in defence of the NHS, or to smash the pay

cap. Nonetheless, unlike any Labour leader for generations, Corbyn can

be pushed to support movements when they develop from below, and which

can then increase confidence to struggle.

The lack of a lead from the

top, however, will not indefinitely prevent new mass movements

developing, possibly very quickly. Both the Brexit referendum and the

general election result were glimpses of the deep-seated anger with the

existing order which is widespread in society, particularly among the

working class and a considerable layer of the middle class, especially

the young. When new viable outlets for this anger emerge, they will be

seized, just as the Brexit referendum was, creating new upheavals which

will again throw all the existing political parties into further

turmoil. Movements could develop on a whole range of issues, including

the catastrophe facing the NHS.

The Labour leadership’s

mistaken approach reflects its programmatic limits. The election

manifesto marked a radical break with the neoliberal policies of Labour

over recent decades. Nonetheless, by historical standards the programme

is very modest, far more limited than was put forward by Tony Benn, or

Jeremy Corbyn, in the early 1980s. Benn called for the nationalisation

of the banks and the top 25 monopolies. It would be inaccurate to

describe Corbynism as rounded-out left reformism. It contains elements

of this but is much more limited. Although Corbyn would consider himself

a socialist, and is seen as one, he does not raise his programme in

terms of the need for a fundamental change in society – for an end to

capitalism and the building of a new socialist order.

Corbyn’s approach is

connected to the beginnings of the new era of radicalisation we are

passing through. Corbyn was correct when he said in his conference

speech last September that "2017 may be the year when politics finally

caught up with the crash of 2008", although it would be more accurate to

say that it began to catch up. There was enormous enthusiasm for

Labour’s radical election manifesto, but there is not as yet mass

pressure pushing Corbyn further to the left.

Labour today

The Labour Party remains two

parties in one: a pro-capitalist party and a new radical party in

formation around Jeremy Corbyn. Had a concerted effort been made to

mobilise the new ‘Corbyn layer’ – with the goal of waging a political

struggle to remove the pro-capitalists from their positions and

completely overturn the party’s undemocratic structures consolidated

over 20 years under the Blairites – hundreds of thousands would have

been enthused to do so. Moreover, in the course of the struggle, they

would have drawn more far-reaching socialist conclusions.

Unfortunately, the leadership

of Momentum (the main pro-Corbyn group in the Labour Party) has acted to

‘police’ the left, keeping out more radical forces, including the

Socialist Party, and attempting to keep the movement within channels

which the Blairites could live with. Momentum’s main selling point is

not its programme or involvement in struggle but its ability to teach

people to canvass in elections. As a result, while a broader layer was

drawn in to door knock in the general election, in most areas there is

limited activity of the fresh layers in the sterile structures of Labour

or Momentum.

On the contrary, the top-down

and unpolitical atmosphere, combined with the Byzantine structures put

in place by New Labour, tends to attract mainly the least radical

elements into playing an active role. The individual attempts to remove

a few Blairite MPs are to be welcomed, as are any measures to

re-democratise the party, but the limited steps taken so far do not

alter the general picture.

The layers of society that

have been drawn into activity are of a mixed character, including a

large layer of the radicalised middle class. As the junior doctors’

strike in 2016 demonstrated, wide sections of the middle class,

especially among the young, are being radicalised by the failure of

capitalism to offer them a future that matches their expectations. They

are increasingly adopting working-class methods of struggle. This is a

very important section of society. Many can be won to a revolutionary

programme in the future. Nonetheless, they do not yet have a fully

working-class outlook. If becoming active in the Labour Party meant

becoming active in a workers’ party, where the organised working class

set the tone, it would be part of completing the process of winning them

to a working-class outlook. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

There is also a layer of

young working-class people who have joined Labour, even if most are not

currently active, but they are not the driving force. Partly, this is

because they are mainly in unorganised workplaces and do not yet have

experience of struggle, although there are important first steps to this

changing with the McDonald’s and Deliveroo strikes. Their consciousness

as Labour Party members is therefore more individualistic than seeing

themselves as part of a class at this stage. This is not necessarily a

permanent feature of Corbynism, and is certainly not a permanent feature

of mass left formations.

While a majority of the

capitalist class hope that Jeremy Corbyn would be more malleable to

their interests on Brexit than the Tories, they fear the massive

radicalisation his election would trigger, and that he could move

dramatically to the left under pressure from below, particularly in the

face of a new economic crisis. This is what the Economist meant when it

feared that Corbyn could see a new financial crisis as ‘Act One in the

collapse of capitalism’. The Financial Times feature on ‘how to hedge

your finances against a future Corbyn government’ quoted two well-known

City fund managers arguing that it is "fear of a Labour government,

rather than fear of Brexit, which is depressing the valuations of

domestically focused UK companies".

In reality, it is both. The

capitalist class is stuck between a rock and a hard place, unable to see

a way forward. On balance, it would much prefer to keep the Tories, led

by May, in power for as long as it is viable. Therefore, while the

government could collapse at any point – felled by Brexit rows, even by

further sexual harassment or other scandals, or by a social explosion –

it is also possible that it will cling on to power for a period.

Even without a new stage of

economic crisis, Corbyn would be under huge pressure from below as a

result of the misery the working and middle classes have suffered over a

whole period. Corbyn’s election programme raised the sights of wide

sections that an alternative to austerity was possible. However, unless

it is accompanied by a general struggle to implement it, against the

opposition of the capitalists, scepticism can return even among those

who have been enthused.

In addition, while it is

positive that the Labour Party in Scotland now also has a more left-wing

leader, Richard Leonard unfortunately supports a continuation of

Labour’s incorrect position on the national question. Labour did recover

some votes in Scotland during the general election, but the numbers

(around 10,000) are just a fraction of the 3.5 million votes gained in

England and Wales. Some further gains can be made but they will be

limited unless the Labour Party, at least, clearly supports the right of

the Scottish people to determine their own future.

The Brexit challenge

Moreover, the desire to

compromise with Labour’s pro-capitalist wing is leading to retreats on

programme. This is particularly the case on Brexit, where the capitalist

class is exerting significant pressure for Labour to put a position

which suits its interests. In the general election Corbyn began to make

some headway among workers who had voted for Brexit by stating that

Labour accepted the referendum result and, more importantly, by

stressing that he wanted a Brexit in the interests of working-class

people and would fight against employers carrying out a race to the

bottom. He combined this with statements against racism and in defence

of the rights of members of other EU states residing in Britain.

As we explained at the time,

at root, the working-class vote for Brexit was a revolt against

everything it had suffered at the hands of the capitalist establishment.

Unfortunately, not least because Corbyn abandoned his historical

position of opposing the EU as a bosses’ club, there was no mass

working-class or left voice expressing that revolt. The Socialist Party,

alongside the RMT, BFAWU and Aslef trade unions, campaigned for a

pro-working-class left exit, but our voices were not strong enough to

counter the establishment campaigns. As a result, the racism and

nationalism of the official pro-Brexit campaigns had a certain effect.

Any growth in racism and

nationalism needs to be combated. However, the pessimism of the majority

of the left, who concluded that the working class had been lost to

reaction, was completely disproved by the enthusiasm that began to be

generated by Corbyn’s general election campaign. The youth were at the

forefront of this but older sections of workers were also stirred by the

manifesto, answering the lie that the central dividing line in society

is now not class but age.

Since the election, Corbyn

has allowed pro-capitalist Keir Starmer to make most of the statements

on Brexit. Up to now the Labour leadership has at least held back from

adopting the pro-remain position that is being urged on it by the

capitalist class and the Blairites. The further it goes in this

direction, however, the more difficult it will be for Corbyn to make

inroads among disillusioned pro-Brexit, ex-Labour voters. One of the

entirely spurious arguments of the Blairites for adopting their position

is that the young people who voted for Corbyn are desperate for him to

do so. This is not the case. Had Brexit been the central issue

motivating young people they would have voted en masse for the Lib-Dems,

rather than Corbyn.

Six months on and Labour’s

support among students has grown further to an overwhelming 68%. What is

key to winning over workers and young people – Brexiters or remainers –

is not Labour’s attitude to the EU in itself, but standing for an

anti-austerity programme that pledges to fight for the interests of the

‘many not the few’. This cannot be achieved if combined with a defence

of the EU neoliberal bosses’ club. That would mean forming a bloc on

this issue with the capitalist class against the forces that made up the

working-class electoral uprising in the referendum.

Labour councils

Another factor that could act

to undermine support for Jeremy Corbyn among a layer of the working

class is the role of Labour where it is already in power: in numerous

local authorities. While Labour nationally declares itself against

austerity, at local level, Labour councils are implementing savage cuts.

Unless Corbyn comes out to clearly oppose their actions, many workers –

already highly cynical about Labour after their experience of recent

decades – can conclude that his opposition to austerity is not serious.

This May, most of the major metropolitan councils in England are up for

election. Many are Labour-controlled already – 86 out of the 151

authorities with elections – but the Tories are panicking that they will

lose some of those they still control, particularly in London.

Following the general

election, there are now much wider layers of society that are

enthusiastic about Corbyn. There will be a mood among some of them,

although it is not clear how broadly, that they have a duty to ‘hold

their noses’ and vote Labour to further strengthen Corbyn’s position,

regardless of who the local council candidate is. How far this will be

cut across by the small number of young people who generally vote in

local elections is not clear. However, Momentum will be able to mobilise

a section of them to canvass for Labour.

At the same time, there will

be other Corbyn supporters who cannot bring themselves to vote Labour

because of the criminal role of Labour locally. There will also be

millions of workers who will vote to express their anger at cuts to

local services. Where Labour is in power this can mean voting to punish

it. The Socialist Party does not favour standing in seats where the

Labour left have won selection contests. Instead, we should pressure

those Labour lefts to adopt a clear anti-cuts stance, while also

encouraging left-wing anti-austerity campaigners to stand against

right-wing Labour candidates.

This is more important than

in previous years because this will be the first election since the

broad politicisation that resulted from the general election. This could

mean that a bigger layer of workers and young people will be thinking

about how to oppose cuts locally. It is also more important because the

strengthening of Corbyn’s position means that the Labour left’s attitude

to council cuts is being tested in practise. Shadow chancellor John

McDonnell has made it clear that he does not think it is possible to

refuse to implement the cuts, using the incorrect argument that the law

precludes the kind of struggles he supported in the 1980s. It would be a

serious mistake if Corbyn and McDonnell continue to put this position,

which will be used by councils as an excuse not to pursue the legal

no-cuts budgets that are entirely possible.

Building a mass movement

Unfortunately, it seems that

the approach of ‘Corbyn councils’ will be on the same lines as the

Bristol mayor, Marvin Rees. He has called anti-cuts demonstrations to

put pressure on the government to stop its austerity programme. This is

to be welcomed – but has been combined with continuing to implement the

cuts! Nonetheless, Rees’s actions have raised the possibility of

stopping council cuts, and given greater opportunities for us to put the

case for councillors to refuse to implement austerity measures. It is

therefore vital that we take the opportunity, including by standing in

elections, to put our programme for anti-cuts councils as an essential

prerequisite for building a movement to defeat the government over local

cut-backs.

Of course, there are bound to

be Corbyn supporters who push aside their worries about council cuts

such is their desperation for a Corbyn-led government. Our duty is to

warn them that a wrong approach to local government could damage the

chance of a Corbyn victory, and to point out that the sabotage a Corbyn

government would face from the capitalist class is as nothing to that

seen so far. Just as with the Tsipras government in Greece, capitalism

globally would try and make an example of a Corbyn-led government,

aiming to show to the British working class, and to workers

internationally, that the left offers no way out.

This does not mean that a

Corbyn-led government could not introduce reforms, but it would be doing

so in the face of the open sabotage of the capitalist class and the

global financial markets. To successfully introduce any significant

reforms would therefore mean mobilising the power of the working class

in support of the government’s policies. Faced with the fear for the

continued existence of their system, the capitalist class can be forced

to go further than their system can afford. This would not stop their

attempts at sabotage, however, and the only way to combat them

decisively would be to take the commanding heights of the economy into

democratic public ownership and to begin to build a socialist planned

economy, calling on workers across Europe and the world to take the same

path.

It cannot be excluded, under

the impact of mass working-class movements, that Corbyn could go much

further in this direction than he currently intends. However, his

approach so far – at best ‘living with’ Labour councils implementing

cuts and a majority of pro-capitalist Labour MPs – does not auger well.

The Socialist Party has an important role to play in reaching out to the

hundreds of thousands of workers and young people who have been awakened

to the idea of struggle and socialism in the last year, fighting

alongside them and explaining what is necessary for the successful

socialist transformation of society. Key to that is the existence of a

mass party capable of leading the working class in that struggle.