|

|

Tremors at the top

While attention has temporarily shifted to the Tory

leadership drama, Tony Blair still finds himself in a weaker position than ever

before. But would his departure from the scene mean the regeneration of the

Labour Party? And what is the alternative to New Labour? CLIVE HEEMSKERK writes.

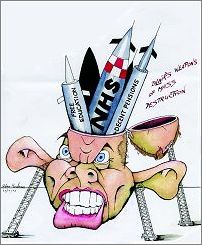

SUDDENLY, TONY BLAIR is looking politically mortal. Even

before his recent health scare – itself symbolising the end of the carefully

constructed image of a ‘new’, ‘young’, ‘dynamic’ prime minister –

speculation on ‘post-Blair politics’ filled the commentary media. SUDDENLY, TONY BLAIR is looking politically mortal. Even

before his recent health scare – itself symbolising the end of the carefully

constructed image of a ‘new’, ‘young’, ‘dynamic’ prime minister –

speculation on ‘post-Blair politics’ filled the commentary media.

No doubt Blair’s advisors were conscious of the

unfortunate parallel with Anthony Eden, prime minister during the 1956 Suez

crisis who, three months after launching an unpopular Middle East war, resigned

citing ill-health (although he lived another 20 years). Before the charge was

even made, Number Ten rushed to deny that there was any connection between Blair’s

heart scare and the stresses of the premiership. This, however, was surely a

case of protesting too much. A series of events have all contributed to making

the past year the most turbulent of his six-year government: Blair’s support

for the US assault on Iraq, the failure to find weapons of mass destruction, the

Hutton inquiry into the persecution of David Kelly (the Ministry of Defence

weapons expert who committed suicide) and the subsequent departure of Blair’s

chief fixer, Alistair Campbell, combined with the growing opposition to his

domestic ‘public sector reform’ agenda. When Downing Street sources are keen

to point out that Blair’s dismal personal poll ratings have "not yet

reached the depths of unpopularity that drove Margaret Thatcher and John Major

out of office" – with a ‘negative rating’ of 29%, compared to 50% and

63% respectively – things aren’t going well. (The Guardian, 25 September)

It was against this background – culminating, on 18

September in Brent East, in the first Labour by-election loss in 15 years –

that the eve-of-Labour conference Guardian leader article spoke of Blair going

to Bournemouth "to start fighting for his political life". (27

September) The chancellor, Gordon Brown, the heir-in-waiting, had only to apply

the coup de grâce and the premiership was his.

In the event, Blair’s position was not seriously

challenged at the Bournemouth conference (see page 3). A key feature of the ‘Blair

project’, to eliminate the element of working class political representation

that previously existed in the structures of the Labour Party, was to transform

the character of the annual party conference. When the Labour Party was a ‘capitalist

workers party’, with a leadership at the top which reflected the outlook of

the capitalist class but with a working class base, the Labour Party conference

was in some respects a ‘parliament of the labour movement’. Constituency

Labour Party (CLP) and union resolutions could change national party policy; and

the unions, with 90% of the conference vote, were potentially able to dominate

proceedings. That has changed fundamentally. The democratic structures were

gradually closed off during the 1980s culminating in the 1997 ‘Partnership in

Power’ structural changes, with policy powers largely removed to more

tightly-controlled national policy forums (NPFs), resolutions restricted, and

the unions’ conference vote reduced to below 50% in favour of CLP

representatives. A left-wing union delegate to this year’s conference found it

noticeable, even compared to recent years, how few of these CLP delegates

"were ordinary party members – they were councillors, NPF members and

candidates for paid posts. One speaker described herself as ex-officio and

turned out to be a member of the party’s staff!" (Dorothy Macedo, Labour

Left Briefing, October 2003) As The Guardian commented, following Blair’s

conference speech, "the fundamental fact about the conference delegates is

that they are mostly public supporters of the government, not public critics.

Whatever their reservations, they had come to praise Caesar, not to bury

him". (1 October)

There are, undoubtedly, growing ‘reservations’ amongst

Labour MPs and councillors that their careers may come to a premature end, their

seats lost, if Tony Blair remains. "Nobody suggests that Labour will lose

in 2005", wrote the former Labour Party deputy leader Roy Hattersley,

following the Brent by-election. "There must be 50 or 60 Labour MPs",

however, "who have begun to question the prime minister’s adoption of the

Zulu battle technique – sacrificing an expendable number of warriors… to

secure his throne". (The Guardian, 22 September) Yet most Labour

backbenchers are placated by the fact that even the best poll position the

crisis-ridden Tory opposition has achieved in recent years would still see a

Labour government returned with a substantial majority. And while Brent East was

lost to the Liberal Democrats, not even an ambitious 10% general election swing

would gain them more than a handful of Labour seats. Nervousness has not yet

turned to panic.

But Blair’s unpopularity is not just another ‘normal’

case of government ‘mid-term blues’ as some commentators have argued,

pointing to the far greater by-election losses suffered by the Labour government

in the 1974-79 parliament. The revelations of the Hutton inquiry – regardless

of the formal verdict now likely to be delivered in the new year – have had a

corrosive effect on his standing. Blair’s appeal during the latest arguments

over the Northern Ireland ‘peace process’, that the different parties would

be satisfied on the decommissioning issue ‘if they knew what he knew’, was

poorly received. Opinion polls show a consistent disbelief of the claim that the

Iraq dossier was not ‘sexed up’. And with the continued failure to find

weapons of mass destruction, a clear majority (53%), for the first time since

the fall of Baghdad, are now saying that the war was unjustified, against those

(38%) who still believe it was right. (ICM poll, 19-21 September)

Underpinning the accumulating discontent, moreover, are the

growing economic difficulties facing the Blair government. With weak economic

growth and consequent falling tax receipts, the public spending deficit for the

first six months of the 2003-04 financial year has risen to £22.5bn, up from

£13.5bn during the same period last year. In April’s budget Gordon Brown

predicted a total annual deficit of £27bn, which now looks likely to be at

least £10bn out. The prospect is that December’s pre-budget report will

include a combination of higher borrowing provisions, a future public spending

squeeze outside of the health and education budgets, and more ‘stealth taxes’

to meet the gap. This will only fuel the discontent. This April, for the first

time since Labour was elected in 1997, real take-home pay fell, by an average of

1.3%, because of higher national insurance (NI) contributions (and lower than

inflation pay rises). Significantly, Labour’s standing as the party with the

greatest ‘economic competence’ has fallen dramatically in opinion polls,

from 47% in March – before the NI hike and council tax rises hit home – to

29% in September. (ICM poll, 19-21 September)

One consequence of this has been the loss of electoral

support for Labour amongst the so-called ABC1 professional, service sector and

skilled manual worker voters. This was New Labour’s ‘new social base’,

with a consistent poll lead recorded amongst this social grouping since 1993,

following the Tory debacle of ‘Black Wednesday’ in September 1992 when the

pound was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (and when the Major

government temporarily raised interest rates to a crippling 17% in an attempt to

avert the crisis).

This potentially is an electorally critical development for

New Labour. The most significant feature of the 2001 general election was the

mass abstentionism that took place, with a 12.5% drop in turnout. Labour’s

total vote fell by 2.8 million (21%) compared to 1997. Only in 1983, after the

formation of the Social Democratic Party, and 1931, when Ramsay MacDonald split

to form a national government with the Tories, had Labour’s absolute vote

fallen by over 20% from one election to the next. And yet there was a

differential rate of ‘flight from Labour’ between the ABC1 electorate and

other voters, with abstention rates rising significantly more in the working

class Labour ‘heartlands’. While a recent ICM poll showed that the Tories

were not putting on support in key marginal ‘middle England’ seats, Labour’s

vote had slumped (The Guardian, 29 September). Unlikely though it seems today

– although more plausible as the hapless Iain Duncan Smith departs – a

further rise in abstentionism, combined with an erosion of Labour’s middle

class support, could yet see the Tories cut into Labour’s majority.

At this stage, however, the Labour government is still the

favoured instrument of rule for Britain’s ruling class. One indication of this

is the fact that, from 2001-03, the Labour Party received nearly three times as

much funding from wealthy business donors, £7.89m, as the Tories, £2.76m

(although, as the role of Tory pay-masters in the unseating of Iain Duncan Smith

shows, the ruling class still wants the Tory Party as a reserve weapon).

Undoubtedly, not the least important factor behind the ‘Betsygate scandal’

– the alleged misuse of public funds by Duncan Smith to pay his wife, Betsy,

for ‘secretarial duties’ – was the growing reliance of the Tory Party on

state money (so-called ‘Short money’, named after the minister who

introduced financial help for opposition parties, and other similar sources),

which provided 55% of its income (£6.89m) in this period.

Blair’s role in the Iraq conflict, including his role in

the inter-capitalist clashes provoked by the US disdain for ‘multilateralism’

and the role of the UN, impacted negatively on British imperialism’s

international standing, not least amongst its key European Union ‘allies’.

Sections of the ruling class clearly feel that this ‘presidential prime

minister’ – the Caesar of the Bournemouth conference – should have his

wings clipped. But overall, largely satisfied with New Labour’s stewardship of

British capitalism, there is no ruling class clamour for a change of government.

Far more attractive, if Blair has to go, would be a managed succession to Gordon

Brown.

This would also have the advantage of allowing some of the

less awkward of the new ‘awkward squad’ of trade union leaders to claim that

they were making headway in their campaign to ‘reclaim the Labour Party’.

Both Dave Prentis, general secretary of the public services union UNISON, and

Kevin Curran, leader of the GMB general workers union, made a contrast between

Tony Blair’s conference speech and that of Gordon Brown. Kevin Curran praised

Brown’s speech, with its 63 unadorned references to ‘Labour’ rather than

‘New Labour’, as having "socialism as its base", while Dave

Prentis called it "inspiring" and "reassuring for public

services". It was, of course, nothing of the sort. Even The Guardian could

see that the "paradox in Mr Brown’s boldness lay in the certainty that he

and the prime minister remain closer on the bulk of the modernisers’ agenda

than the chancellor is to many of Mr Blair’s critics". (30 September)

At present it appears that the most likely way that Blair

will depart the scene will be through a ‘cold transition’ to Brown, possibly

before the general election if events compel (Hutton, the economy, the Iraq

imbroglio), but more likely some time after. This would not mean, however, that

the Labour Party would be regenerated as a vehicle for working class political

representation. It is not even assured that there would be a leadership contest,

given that a nomination for leader needs to have the support of 12.5% of the

Parliamentary Labour Party (52 MPs – or 20%, 82 MPs, ‘if there is no vacancy’).

In the same way, Scotland has seen three Scottish parliament Labour first

ministers elected since 1999 without a single vote being cast by individual

party members or affiliated trade unions. But even an election contest between

candidates who could reach the parliamentary party nomination threshold, say

between Gordon Brown and Robin Cook, would be little different in political

content to a US Democratic Party-style ‘primary’. Cook’s new book, The

Point of Departure – which contains a ‘personal manifesto’ including

commitments to ‘the [capitalist] stakeholder economy’, euro entry and

proportional representation (as a prelude to ‘centre-left co-operation’ with

the Liberal Democrats) – was correctly described by The Guardian journalist

Martin Kettle as "a manifesto for an alternative Blairism… [an] attempt

to put a bit of ideological bite into Labour’s second-term managerialism".

(21 October)

The end of Blair could well mean the end of the terminology

and other superficial aspects of ‘New Labour’. But the core of ‘the

project’ would remain – the elimination of the latent potential for workers’

interests to be politically represented that formerly existed through the Labour

Party.

|