Europe:

eruptions and fissures

Europe:

eruptions and fissures

In April, the Committee for

a Workers’ International (CWI) held a European Bureau, bringing together

socialists from around Europe, and further afield. Among many other

issues, it discussed the overall political and social situation in

Europe. The article below is extracted from the main political

resolution passed by the bureau. Further reports – and the full text of

the resolution – are available from the

CWI website.

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE world

economic and political situation form the background to the crisis

facing the European ruling classes epitomised in the worst crisis to hit

the eurozone since the single currency was launched. The world economy

has experienced a very limited recovery which remains extremely fragile.

The massive stimulus packages that were applied, especially in the US,

China and Europe, have had some effect in preventing a complete collapse

into a depression in the world economy, but have been limited and have

not resolved the underlying crisis.

Although the most recent

figures available refer to an increase in economic growth in the US and

Europe, they do not represent a real growth in capacity and have not

taken production back to the levels recorded prior to the onset of the

crisis. The threat remains of a double-dip in the world economy. The

World Trade Organisation predicts that global trade will expand by 9.5%

this year. Even if this is achieved, it will not make up for the 12.2%

drop in 2009.

The economic recoveries

following the stimulus packages were based on schemes such as ‘cash for

clunkers’ and, in Britain for example, a reduction in VAT. These are

temporary, one-off measures. Investment continues to stagnate or

decline. In February, eurozone unemployment was 10% officially. At this

stage, most of the growth arises from restocking goods, with the

creation of further bubbles from the increased liquidity pumped into the

system by the state. China and Germany have boosted their exports but

the decisive question facing world capitalism is the lack of demand and

the absence of new markets. In the case of Germany, export growth has

been at the expense of its rivals but with no real expansion in its

domestic market. Now the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has revised

downwards its 2010 economic growth forecast for Germany from 1.5% to

1.2% citing the weak financial sector and global trade as its main

concerns.

The few bright spots for

capitalism – such as China, Brazil and, to a lesser extent, India –

could still be hit late by the crisis. China, which is experiencing a

property bubble, could see an economic contraction which would provoke a

social explosion which the regime is desperate to avoid. Even if the

world economy returns to a period of absolute growth, inevitable at a

certain stage, this would be insufficient to resolve the social horrors

and deprivation arising from the crisis, and which face the mass of the

world’s population, or the political consequences.

The current conjuncture,

therefore, is not a recovery in the real sense. It is largely jobless,

with mass unemployment remaining even where there is some limited

growth. In fact, the last 30 years have witnessed an underlying

depressionary period. This was partially masked by the credit-fuelled

consumer booms and a series of speculative bubbles, which have now

largely burst.

Each capitalist crisis

contains within it some period of growth and partial recovery. At a

certain stage, this will give way to a new crisis, recession or

stagnation. The onset of the crisis three years ago represented a huge

ideological blow against capitalism. This compelled the ruling class to

respond with emergency measures of a state-capitalist character, with

the state compelled to intervene in the so-called ‘free market’ to prop

it up and save it. This is entirely different to the ‘post-war

settlement’ and the development of the ‘mixed economy’ after the second

world war. During that time, the bourgeoisie accepted quite a large

element of state ownership and economic intervention accompanied by the

introduction of significant social reforms. In contrast, today,

intervention and nationalisations are sudden and short-term attempts to

stave off imminent collapse, followed by fairly rapid proposals for

privatisation combined with brutal counter-reforms and attacks on living

standards.

Crisis in the eurozone

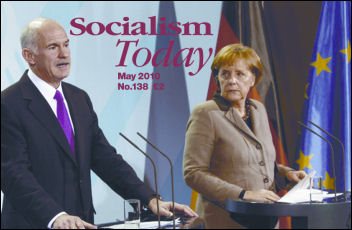

THE MOST SIGNIFICANT European

development so far this year has been the drama erupting from the debt

crisis in Greece. This has had international repercussions and triggered

a major crisis in the eurozone and EU. It has brought to the fore sharp

national antagonisms between Germany, Greece, France and other EU

powers.

This has revealed the

relative weakness of the euro and has brought into question its

survival. This uncertainty represents a serious setback for the European

ruling classes. To defend its own national interests, Germany refused to

simply bailout Greece. The hard line adopted by chancellor Angela Merkel

reflects the fear of German imperialism that, by bailing-out Greece, a

precedent would be set, as impending crises erupt in Spain, Portugal and

elsewhere. Showing a new assertiveness, Merkel threatened that countries

which run into crisis could be thrown out of the eurozone. On the other

hand, allowing Greece to default ran the risk of triggering new

financial and political firestorms.

The reaction of other

European powers, especially France, turned the situation into a European

crisis. That exerted immense pressure on Germany to modify its position.

The decision to include the IMF in bailing-out Greece is a blow against

the prestige of the eurozone bourgeoisies and the European Central Bank

(ECB). One of the initial ideas behind the formation of the single

currency and ECB was to establish a counterweight to US imperialism and

the IMF. So, recent developments are a far cry from the halcyon days of

triumphant European capitalism, when the euro was launched with high

expectations of economic growth, a strong currency and a smooth path

towards ever greater European integration. Some argued that this would

eventually overcome national antagonisms and result in the end of

national bourgeois states in the EU.

These pipedreams –

consistently opposed by the CWI – have been exposed by the sharp rise in

national antagonisms. The crisis has revealed the impediments to real

integration and the failure to overcome the limitations of the nation

state and the interests of the ruling class in each country. The degree

of European integration has probably reached its limits, with the

process stagnating, even going into reverse.

The euro crisis will not mean

that the currency will be simply abandoned. However, some countries may

fall out of the straitjacket it imposes. The degree of national

antagonism, provoked by Germany’s defence of its own interests, was seen

in references to German imperialism’s role in Greece during the second

world war. French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, was quoted in Le Monde

saying that German imperialism "has not changed". This conflict

represents a departure from the previous period when France and Germany

tended to act as allies, at least within the context of the EU. At the

same time, it leaves French imperialism in a precarious situation as it

does not want to ally itself with British or US imperialism.

German capitalism has been

able to exploit the exchange rate to its advantage, and has used its

power to compel an unwilling France to accept its position. Germany is

the motor for European growth. And it is trying to put the rest of the

continent on rations, demanding drastic austerity programmes, especially

in the weaker EU economies.

A ferocious nationalist

campaign has been conducted by the German ruling class against the Greek

people. This indicates that nationalist sentiments can be bolstered by

the ruling classes as the crisis unfolds. This has to be counteracted by

strengthening the idea of a united struggle by all European workers

against cut-backs and attacks. While it may be premature to demand an

all-European 24-hour general strike, at this stage, the idea of

European-wide protests can be taken up energetically.

Features of depression

THE CRISIS HAS been

devastating for central and eastern Europe. The high hopes that came on

the back of capitalist restoration, following the collapse of Stalinism

in 1989-90, have not materialised for the masses. The economic meltdown

in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia is on a par with the great depression

of the 1930s. Hungary is faring little better. Although Poland appears

to be the exception, the growing public debt, which threatens to breach

55% of GDP next year and 60% soon after, will force cuts and attacks on

the working class. To this must be added the catastrophe unfolding in

Russia. Unemployment is probably higher than in 1994 when production

collapsed. The regime is beginning to split and a social eruption is a

serious prospect in a relatively short period of time.

National antagonisms can also

manifest themselves in a resurgence of the national question and

tensions within countries, such as Spain and Belgium. In Northern

Ireland, the impossibility of solving the national question under

capitalism is reflected in a growth of sectarian conflict in the

communities despite the continuation of the so-called ‘peace process’ at

the top. As the crisis has hit Spain extremely hard, so the wave of

struggle by the working class has developed rapidly. At the same time,

there has been a growth of regional and national sentiment, especially

in the Basque country, Catalonia and other areas. Forty percent of state

expenditure is administered in the regions and provinces. This can

become a focal point of conflict with the national government. The

national rights of the peoples of Spain need to be defended at the same

time as fighting for a socialist confederation and struggling for a

united working class throughout the Spanish state.

In a sense, the threat of a

default by Greece includes elements of 1980s Latin America – including

the demand of non-payment of the debt. Significant as this is, it is an

anticipation of the even bigger crisis waiting to erupt in Portugal, and

especially Spain. With nearly 20% unemployment and up to 40% youth

unemployment, a social revolt at least as strong as in Greece is posed.

The effects and depth of the crisis have not been uniform. But Portugal,

Ireland, Greece and Spain have been devastated and show some features of

a depression comparable with the 1930s. The Irish economy is still

contracting. These countries, under the insulting acronym, PIGS, have

been widened to STUPIID: Spain, Turkey, the UK, Portugal, Ireland,

Iceland and Dubai!

Compelling workers to struggle

INTERNATIONALLY, THE RULING

classes seek to drive down further living standards, wages and

conditions. The political and social consequences are decisive issues.

Perspectives and tasks have never been more intertwined. In general, the

impact of the crisis on the class struggle has still to be fully felt.

Yet, already, important mass movements have erupted, especially in

Greece, Spain and Portugal. In other countries, working-class struggle

would have gone a lot further but for the cowardly role of the trade

union leaders who have reflected, in general, the interests and pressure

from the employers rather than fought to defend the working class.

To this must be added the

crucial question of the currently limited level of political

consciousness of the working class – inherited from the previous period

and hindered by the failure of the official workers’ leaders to offer a

real socialist alternative. These weaknesses mean that the crisis will

be complex and protracted. Despite this, massive social explosions, and

industrial and political struggles, will unfold and can allow socialist

forces to build rapidly, with the correct slogans, tactics and

explanatory socialist propaganda. This will not be an automatic or

straightforward process. The rhythm of the struggle and the development

of political consciousness will vary from country to country.

Added to the economic and

political crises is that of the environment and global warming.

Increasingly, the consequences of global warming are becoming an issue

among the working class, as they are felt mainly by the workers and

poor. This has been the case even in Europe, as witnessed in the

movements over water supplies in Andalucia. A section of the bourgeoisie

has raised the prospect that new ‘eco-industries’ offer a solution to

the economic crisis. However, it is highly unlikely that this provides a

rapid, short-term road to recovery or new markets on which the

capitalists can sell their products.

Despite the contradictions in

political consciousness among big sections of the working class and

youth, it would be a mistake to underestimate the underlying bitterness

and anger which is present. This is not, in the main, reflected in the

official trade unions or their structures.

There have been significant

industrial movements of workers in many countries in response to the

crisis and attacks on the working class. In the main, these have been

defensive. The first half of 2009 in Ireland saw important strikes and

protests. The public-sector strikes and three massive general strikes in

Greece graphically illustrate how the working class has been compelled

to struggle. The public-sector strikes in Portugal and the threat of a

general strike illustrate the desperation of the situation faced by

workers. The massive demonstrations and overwhelming demand for a

general strike have terrified the ruling class in Spain but also in

Europe as a whole. Although Turkey is not geographically fully a part of

Europe, socially and politically it has increasingly become part of the

European discussion. The tremendous TEKEL strike represents a crucial

change in the situation there.

Spain, with a larger economy

and more powerful working class than Greece, could be thrust to centre

stage at any time. Significantly, the fear of such an explosion has

compelled the government to withdraw its proposal to raise the

retirement age. There were elements of a pre-revolutionary situation

during the height of the movement in Greece. The failure of the official

workers’ leaders to offer an alternative, the more limited level of

political consciousness, together with the weakness of organisation from

below, were the main obstacles. Yet, the masses are further to the left

than the leadership.

Similar pre-revolutionary

elements can develop in this new era in a number of European countries

in the coming months and years. But the processes will be more complex

and protracted precisely because of the absence of mass workers’

organisations.

In Britain, following last

year’s industrial struggles at Lindsey, Linamar, Vestas, and by postal

workers, 2010 has seen national strikes at British Airways and by

government workers. Rail workers could soon join the list. This

indicates a new situation. France saw a national strike called on 23

March. In Belgium, some strikes have been initiated from below.

These and other movements

have happened in spite of the trade union leaders who have been

terrified by the crisis. In France, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Spain and

Sweden they have sought to re-establish ‘social dialogue’ and ‘social

contracts’, and avoid calling serious national action. They have argued

for wage cuts to stave off unemployment and acted as arbitrators between

the employers, their governments and the working class. Generally, when

the trade union leaders have called protest action, it has been merely

to let off steam. The willingness of some workers to struggle was

reflected in Ireland by the 83% vote for action in the CPSU government

employees’ union. A similarly high vote for action was seen at British

Airways.

The general strike

IN ITALY, DESPITE a growing

wave of opposition to prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi – shown in

massive demonstrations in Rome and Milan – the CGIL union confederation

only called a four-hour general strike. Objectively, the question of the

general strike is present throughout Europe. When relevant, this should

be advanced as a main slogan. In countries like Greece, where a series

of general strikes have been called but have not been pursued with a

clear programme of action and a political alternative, the call for a

24- or 48-hour general strike needs to be raised. If that does not

compel the government to retreat, more decisive and protracted action

could be posed, including an all-out strike.

However, the situation today

is more complex than in the past because of the character of the trade

union leaders and the political consciousness of the working class. The

general strikes, or partial general strikes, which have taken place have

assumed the role of protest actions – more comparable to those in some

European countries prior to the first world war. Further action, perhaps

of a lengthier time than 24 or 48 hours, the election of action

committees, and the need for a KKE (Communist Party) and SYRIZA

government on a socialist programme, were raised in Greece. Similar

demands will need to be developed in other countries where appropriate.

Ultimately, an indefinite general strike will pose the question of

power. Yet, at this stage, the political consciousness of the working

class lags behind that task. Specific, concrete proposals during

industrial struggles – how to organise, and what action to take – are

especially important because of the lack of experience in struggle by a

new generation of workers.

The balance between

intervening in the official trade union structures and, where

appropriate, proposing the formation of unofficial,

democratically-elected action committees outside the official structures

is especially important. This has been re-enforced by the decline in the

number of unionised, especially young, workers and the role of the union

bureaucracy. The growing number of younger workers who have temporary

jobs without permanent or fixed contracts is also a factor.

Although significant, the

industrial movements which have taken place only represent the first

reaction to the impact of the crisis. There have also been different

phases in the development of the political consciousness of workers.

Initially, a certain radicalisation took place among many. Following an

outburst of anger and anti-banker, anti-rich awareness in some

countries, there has also been a certain stunning effect at the depth of

crisis: ‘We have to accept some belt-tightening’. In others, there has

been a hope-against-hope that the crisis and its consequences would be

short term. This was followed by a certain expectation that the stimulus

packages would solve the problem and life would return to ‘normal’.

In Ireland, the cowardly role

of the trade union leaders has compounded the problems of working-class

political consciousness and confidence. After more than 20 years of

economic growth, the working class has been faced with an economic

tsunami. A bitter, reluctant acceptance that cuts are ‘inevitable’ –

that there is no alternative in such an economic collapse, and in the

absence of a mass alternative – has prevented a movement from below

developing thus far. However, this can rapidly give way to a massive

social explosion and, sometimes, can be triggered by a relatively small

attack following a series of harsher measures.

The lack of a strong socialist alternative

THE ABSENCE OF a clearly

defined and powerful socialist alternative and consciousness is the main

obstacle to a mass mobilisation for socialist change. The bourgeoisie

can count itself lucky that it does not encounter even a powerful

left-reformist or centrist force with roots among the working class as

existed in the past. The absence of a mass socialist alternative is

reflected in a higher rate of abstentions in elections in many European

countries.

Hardly a single government in

Europe can be regarded as stable. This instability is reflected in

Merkel’s government, with open clashes between the CDU, CSU and FDP

right-wing coalition ministers. In Italy, the resurgence of opposition

to Berlusconi and the fall in his approval ratings are further

indications of this, although the expected collapse of the centre-right

in regional elections did not take place. The Italian ruling class is

clearly concerned about Berlusconi. The existence of a powerful left

force in most countries would have swept the existing governments or

parties from power.

Faced with this, the

emergence of ‘lesser evilism’ marks out the situation in many countries.

For a time, this was reflected in Greece with the re-election of the

social-democratic PASOK. Regional elections in France saw the

proportional growth in the vote of the Parti Socialiste. In Ireland, the

Irish Labour Party rose in the polls. Even in Britain, after 13 years of

New Labour, fear of a Tory government means that Gordon Brown could get

a better result than appeared likely a few months ago. This could even

bring a minority New Labour government, possibly in an unofficial

coalition with the Liberals. A minority Tory government also remains a

possibility but, such is the inflamed social situation, such a

government could be extremely short term.

Proportional increases in

electoral support for the former social-democratic parties, however, are

not on the same basis as in the past. They have far weaker social roots

and the expectations in them are much less. The parties which

proportionally have grown electorally have not experienced an upturn in

active, working-class membership. There can be extremely rapid changes

in mood, with growth in electoral support for a political party

evaporating and turning into bitter opposition.

Most graphically, this was

seen in Iceland following the election of the Social

Democratic/Left-Green Alliance. Within a few months, hopes in this

government – the first time a Social Democratic government has been in

power in Iceland – were dashed. The government proposal to accept the

repayment terms demanded by the British government met with fierce

opposition. Even the right-wing president was compelled to reflect this

mood and refused to sign the agreement. This opened the way for the

referendum in which 93% rejected the deal.

The new left formations

GENERALLY SPEAKING, THE new

left alliances/parties have failed to fill the political vacuum. Their

futures are unclear. Faced with an historic crisis of capitalism they

have tended to move to the right and a further ideological collapse has

taken place. This is one of the main reasons why these new formations

have not developed recently. The NPA (Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste) in

France and SYRIZA in Greece have fallen back from opinion poll high

points. The election result of the NPA (2.5%) and the Dutch Socialist

Party were in marked contrast to the tremendous electoral victory in

Ireland of the Socialist Party’s Joe Higgins in the European elections.

In Germany, Die Linke, despite a marked shift to the left in words in

its recent Draft Programme, has remained static at around 11%. However,

it may succeed in entering Germany’s largest regional parliament,

North-Rhine Westphalia, for the first time. This will be seen as a

success.

At this stage, the new left

parties/alliances have not attracted large numbers of workers into their

ranks. This partly reflects their failure to offer a clear, consistent,

socialist alternative. It is also an inability by the leadership to

combine election work with intervention in struggle. In part, it

reflects a general anti-party sentiment by many workers and youth who do

not yet see why they should get actively involved in a political party.

This will change as workers –

though the continuation of the crisis, their experience in struggle and

the intervention of socialists – conclude that they have no alternative

but to develop their own political voice. This is not straightforward.

It may require a series of struggles before a powerful left force with a

substantial active participation by workers is built in any European

country. It remains unclear whether the existing forces will develop

further or if new organisations will emerge. Nonetheless, participation

in existing organisations is important, to try to shape how they

develop, and can have a significant impact, as in SYRIZA and P-SOL (in

Brazil). The emergence of various left-wing groupings in SYRIZA

represents an important step forward and may shape how it and a mass,

working-class socialist party develops in Greece. The Trade Unionist and

Socialist Coalition in England and Wales is also significant arising,

partly, from effective intervention in industrial struggles. There will

be many twists and turns along the way, and tactics will need to be

adjusted accordingly.

The formation of new parties

is not an end in itself but a lever for safeguarding and improving the

rights and conditions of the working class. Even once they are formed as

powerful parties involving important sections of the working class and

youth, if strong Marxist forces do not help shape their development,

reformist or even centrist elements can undermine or destroy them

through a wrong programme, tactics and methods. That was the experience

of the PRC (Rifondazione Comunista) in Italy. Where this is allowed to

happen, the disappointment which follows can make building a new force

even more complicated. The vote for the Left Federation – a bloc of the

PRC, PDCI (Italian Communists) and other left groups – averaged a mere

3% in the regional elections. The failure of the PRC, combined with the

Democratic Party’s ineffectiveness, has opened the way for the emergence

of the Purple People movement. Similarly confused and amorphous

developments can emerge in other countries if new mass workers’ parties

are not built.

The formation of new broad

workers’ parties is an important task for the working class and

socialists, but their absence is not a barrier to strengthening

socialist influence. While a larger layer of the working class would be

drawn into such parties, an important layer can also be drawn directly

into socialist parties.

One of the issues to emerge

in Die Linke, SYRIZA, PRC, NPA and PSOL is that of coalitions and

alliances with former social-democratic parties. This requires taking a

principled position alongside skilful explanation which takes into

account the illusions in such coalitions. In the past, this question was

more readily understood by left-wing activists, a further reflection of

how consciousness has been thrown back since the collapse of the former

Stalinist states.

Reaction… and radicalisation

THE ABSENCE OF a left

alternative has resulted in the growth of the far-right in some

countries. The renewed growth of the Freedom Party of Austria, the

possibility of a strong vote for the British National Party in Britain,

Le Pen’s electoral resurgence in local elections in France (on average

winning 17% where the Front National stood), the gains of the far-right

in the Netherlands and the growth of the Liga Nord in the Italian

elections illustrate the danger. The impact of the economic crisis is

reflected in a reactionary way in the growth of racist, anti-immigrant

and anti-Islamic sentiment among some layers. Far-right and right-wing

forces have frequently used right-wing populist rhetoric to win

electoral support. Anti-racist activity needs to be put to the fore.

Demands and programme need to be developed to oppose racism and fight

for class unity by engaging in a dialogue with all layers of the working

class.

With attacks on education and

the rapid growth of unemployment (21% of youth who want to work are

unemployed across the eurozone, according to the OECD), an explosive

situation is unfolding. The movements on education in Germany, Austria

and Spain anticipate other struggles which can develop throughout

Europe. The attacks arising from the Bologna agreement are having

devastating consequences on education and can provoke even bigger

protests. These mobilisations need to turn towards united struggle with

the working class. The youth act as the light-cavalry and are an

anticipation of the more powerful movements of the working class which

often follow them. And a significant layer of young people are entirely

opposed to the existing parties, to the establishment and system as a

whole. Many are in a constant struggle with the police and state

machine. Some are becoming increasingly alienated from society.

A layer has been drawn

towards anarchistic organisations and ideas. The degree of alienation of

some youth is already reflected in Greece with the emergence of some

terrorist groupings. This negative reaction can also develop in other

countries. The anger and bitterness of the best of these youth are

justified and need to be reflected by socialists. While not succumbing

to ultra-leftism, the political approach to young people should not be

too timid. Despite all the problems facing the workers’ movement, there

is a new, favourable situation in Europe for the development of more

substantial Marxist parties.