|

|

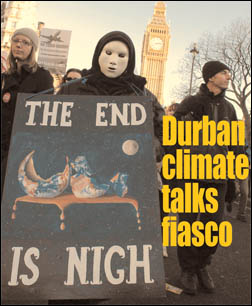

Dithering in Durban Dithering in Durban

Once again, a United Nations-sponsored climate

change conference has completely failed to address the issue of global

warming. Indeed, the latest attempt – in Durban, South Africa, last

December – pushed any hope of a deal back to beyond 2020, already far

too late for meaningful action in the view of most climate change

scientific opinion. PETE DICKENSON reports.

DESPITE ITS UTTER, abject failure, the chair of the

conference, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, proclaimed a resounding success.

Referring to a ‘plan A’ (supposedly legally binding), rather than a

voluntary ‘plan B’, she said: "we have concluded this meeting with plan

A to save our planet for the future of our children and our

grandchildren to come. We have made history". (The Times, 12 December)

Chris Huhne, Britain’s energy and climate change minister, added: "This

is the first time we have seen major economies commit to take action

demanded by the science". (New Scientist, 17 December)

Anyone familiar with the seriousness of the

environmental situation would have to assume that these statements

reflected either the deepest political cynicism, or self-delusion almost

on a level requiring medical intervention. Nothing substantive was

agreed on either count, legal or scientific. All the conference ended

with was a hope that a new and as yet unspecified agreement to replace

the Kyoto climate reduction treaty, that ends this year, would come into

operation by the earliest in 2020. That is, no new deal will be in place

between now and then, when the consensus of climate science says that

the greenhouse gases causing global warming must be cut by 40% in less

than ten years to avert a potential catastrophe. Moreover, the wording

agreed to form a legally binding basis for a future treaty was so vague

as to be worthless.

The evidence available to the delegates was ominous

(see boxes). The International Energy Agency (IEA) warned just before

the meeting that the planet was heading for "irreversible and

potentially catastrophic climate change", and that carbon dioxide

emissions, which account for most global warming, rose by 5% in 2010 to

record levels. This was despite the onset of the economic crisis of

2008, that many expected would temporarily mitigate the problem.

Vague and meaningless

JUST AS AT the UN-sponsored summit in Copenhagen in

2009, the talks were marked by confrontation and acrimony. The key

issues were whether any future protocol would be legally binding and, if

this was agreed, what the targets would be and when would they have to

be met. In the end, what the new targets would be was not even

addressed. The conference overran by two days just arguing over the

legal standing of any agreement.

The final form of words – that by 2015 governments

would finalise a "protocol, legal instrument or an agreed outcome with

legal force" to impose pollution targets – was so vague as to render it

meaningless. Inevitably, it will become the subject of interminable

wrangling in the coming years. When a successor treaty to Kyoto would

begin operation was not included in the agreement. All we were left with

was a pious hope from the organisers that enough countries would ratify

any treaty by 2020 for it to come into force. The looseness of the legal

formulation was the only reason the US and Chinese administrations were

not opposed to the final agreement, in public at least.

Along with agreeing future emissions targets, the

issue of when a new treaty would begin is a crucial one. The

overwhelming opinion of climate science is that carbon emissions should

be cut by 40% by 2020 to have a 50% chance of avoiding a rise in global

temperature of 2°C that could cause potential devastation. Many

scientists believe that even this target is insufficient, and we should

aim for a rise of just 1.5°C.

The outcome of the Durban summit is that not one

gram of carbon will be cut before 2020. In fact, carbon emissions will

continue to rise at an accelerating rate until then if present trends

continue. Also, given the long track record of failed UN talks, and the

highly antagonistic and confrontational atmosphere at Durban, it is

almost inconceivable that anything meaningful will be achieved by 2020,

still less by 2015, the target date for the conclusion of the talks.

Another crucial question, what any new targets would

be, was not even discussed. Fixing new targets was particularly

important because Kyoto was rigged so that no meaningful reductions at

all were demanded. This was to try to encourage the USA to take part –

without success. This time, the targets were meant to reflect the dire

real situation, not political expediency, so the failure even to begin

to address this issue was a hammer blow to the credibility of the

process, although not surprising in the acrimonious circumstances of the

talks.

Global fund deadlock

THE PROJECTED INCREASE in greenhouse gas output

between now and 2020 by China alone will destroy any chance of meeting

the 2°C target for global warming. What position it takes in the coming

decade will be vital therefore. Although no official discussions took

place in Durban on targets, the Chinese regime made it clear, as it has

for years, that no target for greenhouse gas reductions would be

acceptable. All that will be on offer, and this conditionally, is for a

commitment to reduce the intensity of carbon use. (Intensity means the

amount of carbon outputted per unit of GDP, a measure of the efficiency

of carbon use.) However, even if China increases energy efficiency, if

its economy continues to grow more quickly than intensity falls, as has

been the case, then total emissions will rise.

China, India and other countries trying to

industrialise say, reasonably, that the ex-colonial countries should not

be expected to pick up the bill since global warming has been caused

mainly by the big imperialist powers. Also, the USA, Japan and the EU

should not be able to wash their hands of the problem as they ‘export’

their emissions to China through off-shoring production. Recognising

this position, the conference was supposed to come up with an agreement

on a special green climate fund that would give financial assistance to

help poorer nations to address climate change.

One of the few, tiny advances at Copenhagen was to

set up this fund, which was to be worth $100 billion a year. No money

was forthcoming, though. So, one of the tasks for Durban was to set up a

funding mechanism for this programme. Before the summit, this was spun

as one of the areas where real agreement would be reached, even if there

were problems elsewhere. In the event, there was total deadlock on this

issue, too. With no agreement, any possibility that China and India

would contemplate future actual cuts in emissions, rather than just in

energy intensity, was eliminated.

Voluntary agreements

SURVEYING THE WRECKAGE of yet another failed summit,

the world is left with a reliance on the voluntary agreements that were

promised after the collapse of the Copenhagen talks. As subsequent

experience has shown, these were hardly worth the paper they were

written on, as governments were responsible for setting their own rules

and policing them. For instance, the US administration had promised to

cut greenhouse gases by 17% from 2005 levels, but will not say what

emissions were in that year. "They keep changing the data", said Marion

Vieweg of Climate Analytics, a climate modelling group in Germany (New

Scientist, 17 December).

The Brazilian government said it would cut output by

36% from ‘business as usual’ projected growth, but decided this year to

change its (self-determined) definition of business as usual to permit

an extra 18% of emissions. China’s regime agreed to cut carbon

intensity, but refused to give a projection of economic growth, making

it impossible to calculate the potential impact on the environment.

The EU, as at Copenhagen, played a cynical,

hypocritical role, posing as a champion of the environment, in

particular pressing for more stringent targets and a tougher legal

framework than most others wanted. Its positions, however, were always

conditional on agreement being reached with all parties at Durban, and

would be withdrawn otherwise. Since it was perfectly clear in advance

that there was no chance that the US and China, in particular, would go

along with the EU’s demands, it was safe to pose as much as it liked. In

the end, of course, the chief EU negotiator, Connie Hildegaarde, signed

up to an agreement with a nebulous legal framework with no emissions

targets at all.

The EU did agree to continue implementing Kyoto

after this year, but this gesture failed to refute suggestions that it

was grandstanding, as it refused to say for how long this commitment

would last, or what the new targets would be for emissions reductions.

In the very unlikely event that meaningful EU targets and timescales

emerge, the gesture would still have little impact on global warming

because the Kyoto nations now account for only 15% of total emissions as

a result of Japan, Russia and Canada pulling out.

What needs to be done?

THE FAILURE OF the Durban summit – and, previously,

the one in Copenhagen – which were meant to correct the failings of the

Kyoto system, demonstrates graphically the inability of the capitalist

class to tackle global warming. In particular, Copenhagen – a meeting

that the UN in advance had called the last chance to avoid catastrophic

global warming – revealed the antagonistic relations lying at the heart

of imperialism, preventing agreement on climate change.

Rather than the Kyoto-type cap-and-trade system

discussed at Durban, many activists are now calling for direct measures

to be implemented to reduce greenhouse gases. They say that laws should

be introduced to establish a ceiling on emissions by a certain date, any

transgressions being dealt with using criminal sanctions. However, if

the bourgeoisie opposed the largely cosmetic measures proposed at Durban

and Copenhagen, any new approach with real teeth would meet with even

more determined resistance. The evidence is now overwhelming that,

despite their fine words, the ruling capitalist class in Britain and

internationally does not intend to take any meaningful action to tackle

global warming in the foreseeable future.

Indeed, the financial and economic crisis that began

in 2007 has made it likely that even token, half-hearted measures, like

the Kyoto treaty, will be opposed by most states. For instance, the US

administration resolutely refused to participate in an international

treaty to reduce greenhouse gases, even when it was offered a system at

Copenhagen that was full of loopholes. Environmental activists should

join with the labour movement to fight the do-nothing policies of the

capitalists. However, as well as campaigning for decisive action,

political lessons must also be drawn from the 20 years that have already

been lost in the battle against global warming, since the Rio earth

summit in 1992.

The failure of market approaches to tackle this

issue points to the need for a radical policy that addresses the root of

the problem: the capitalist market system and the imperialist rivalry

between nation states that it has spawned in the last 100 years. A

change in the social system is the only way that will allow us to live

in harmony with the natural environment into the foreseeable future. The

premise for this must be the common ownership of the means of life,

applied on an international scale, which would remove the antagonism

between nation states that is threatening to destroy the planet.

By taking no meaningful action for the past 20

years, the representatives of the capitalist market system have created

a situation where some of the effects of global warming are probably

irreversible, or at least cannot be reversed for hundreds of years.

Whatever happens now, this is an historical indictment of capitalism,

which could eventually rank in its consequences alongside the greatest

crimes for which capitalism has been responsible, such as the

imperialist wars of the 20th century.

To avoid the worst effects of climate change,

decisive action needs to be taken now. Yet there is no sign at all of

this happening, due to the rivalries of the main industrial powers. This

presents a grave warning to the labour movement internationally that the

task is urgent and it falls on our shoulders to implement a programme

that can tackle global warming. The essential step in making this a

reality is to replace capitalism with a democratic socialist system. The

longer this is delayed, the worse will be the situation we inherit.

The scale of the problem

SINCE THE early 20th century, global

temperatures have risen rapidly, so far by 0.7°C. A rise of 0.7°C

may not seem big, but this needs to be compared to the figure of

2°C, beyond which it is widely accepted that global warming effects

could become irreversible. Predictions of future warming cover a big

range, depending on the assumed sensitivity of the earth to the

concentration of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. The present

concentration is about 430 parts per million carbon dioxide

equivalent in the air (430ppm CO2e). The equivalent

figure is often used so that the whole range of greenhouse gasses,

most significantly methane, is taken into account.

It has been estimated that a figure of 400ppm

could result in temperature rises of between 0.6°C and 4.9°C

depending on assumed sensitivity. A concentration of 1,000ppm could

produce rises in the range of 2.2°C to 17.1°C. The International

Energy Agency (IEA) estimated in 2006 that emissions will more than

double by 2050 on current trends, which could result in a

temperature rise of 1.7°C-13.3°C. Also, the predictions here could

be conservative because of so-called tipping point effects.

Tipping points, sometimes called positive

feedback effects, reinforce global warming in various ways. For

instance, the role the oceans currently play in absorbing carbon

dioxide could be switched to one of emitting the gas. This could

happen because, as sea temperatures rise due to global warming, the

oceans’ ability to absorb further carbon dioxide is reduced.

Another serious tipping point threat is the

possible collapse of the global ocean circulation system. This could

shut down the Gulf Stream and affect the Asian monsoon, leading to a

warming of the southern oceans and the destabilisation of the west

Antarctic ice sheet. At the same time, the El Niño current in the

Pacific could become a permanent feature, hastening the

disappearance of the Amazon rainforest, an important absorber, or

sink, of carbon dioxide. Already, the Amazon turned into a net

emitter of carbon dioxide during two monster droughts in the last

ten years.

Connected to the disruption of the ocean

currents is another tipping point, linked to the melting of polar

ice. The absence of polar ice to reflect the sun’s rays back beyond

the atmosphere will further reinforce global warming.

Perhaps the most serious (although the most

unpredictable) positive feedback phenomenon, however, is the release

of methane into the atmosphere. Methane has a far more toxic effect

than carbon dioxide in relation to global warming and, potentially,

vast quantities could be released as the earth warms. Methane

presently trapped in the permafrost is equivalent to double all the

greenhouse gas emissions yet made and it is not clear to what extent

it will be released as temperatures rise in permafrost regions. Even

more methane is under the oceans, kept in place by sufficiently low

temperatures and high pressures. If ocean warming penetrated deeply

enough it is theoretically possible that some of this gas could be

released, with catastrophic effects.

Effects of global warming

THE SENSITIVITY of the earth to greenhouse gases

is an area that is not yet fully understood but, if the upper end of

the International Energy Agency estimates, 13.3°C, proves to be

true, it will be difficult for life to be sustained on the planet.

Although this extreme outcome is statistically unlikely, it is

nevertheless a warning of the profound dangers we face. A recent,

lower, and much more likely prediction, which would nevertheless

still be devastating, is for a rise of 4°C by 2055 – made by the UK

Met Office, a leading authority in climate science.

According to Wolfgang Cramer at the Postsdam

Institute for Climate Research in Germany, a 4°C rise would see 83%

of the Amazon rainforest destroyed by 2100. His colleague, Anders

Levermann, has developed a model predicting alternating extreme

monsoons and droughts in China and India that will threaten

irrigation systems and access to drinking water. Overall, lack of

water, crop failure and rising sea levels could force up to 200

million people from their homes by 2050.

The 2006 Stern report into climate

change, commissioned by the former New Labour government in Britain

and then ignored, assumed a 2-3°C rise. It also predicted more

frequent droughts and floods, as well as declining crop yields and

fish stocks, with tens or hundreds of millions of people flooded out

of their homes. Climate change will also increase deaths from

malnutrition, heat stress and diseases such as malaria and dengue

fever.

An important new development facing the Durban

conference was the evidence of massive greenhouse gas production in

China, to the extent that it is now the world’s biggest emitter.

This is due significantly to the transfer of pollution from the main

industrial countries as they offshore their manufacturing. This

process of western powers’ ‘exporting’ their emissions to China has

accelerated dramatically, according to a report by the National

Academy of Sciences in the USA.

China’s carbon dioxide output increased from

four to seven gigatonnes in the six years from 2002, overtaking the

USA. China alone will produce as much carbon dioxide between 2010

and 2035 as the US, EU and Japan combined, quoting figures from the

IEA. Incidentally, if the effect of this outsourcing of pollution is

taken into account, Britain’s emissions would rise by 100 million

tonnes and China’s would fall by a fifth. Given this projection, no

agreement in Durban would have had any significance if it did not

address what is happening in China.

|