Italy’s

clowns: no joke for establishment parties

Italy’s

clowns: no joke for establishment parties

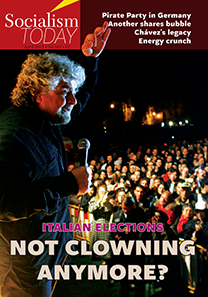

Comedian Beppe Grillo and

the Five Star Movement have taken centre stage following Italy’s general

election in February. It is the latest, dramatic manifestation of the

widespread rejection of establishment politics. CHRISTINE THOMAS reports

on this new political phenomenon.

The shock result in the

recent Italian elections reverberated around the world, leading to

market instability and fears about the possible economic fallout. The

Five Star Movement (M5S – Movimento 5 Stelle), launched by the comedian

Beppe Grillo just four years earlier, emerged as the biggest single

party, with more than 25% of the vote. "We channelled all the anger in

society", said Grillo, summing up this election ‘victory’ in an

interview with the international press (he refuses to speak to the

Italian media).

While workers and youth in

Greece, Spain and Portugal have been waging general strikes and taking

to the streets in their millions in opposition to a never-ending

austerity onslaught, in Italy there has been relative quiescence. This

is in spite of the devastating economic impact on ordinary people, with

living standards falling to the level of 27 years ago. But, on 24/25

February, all the accumulated anger and dissatisfaction poured into the

ballot boxes, with the M5S becoming the main beneficiary.

In packed electoral rallies

in piazzas all over the country, Grillo’s cry of "tutti a casa" (send

them all packing) had a particular resonance with a population sick to

the stomach of the corrupt, moneygrubbing, self-seeking politicians of

the establishment parties, and of the industrialists and bankers

involved in scandals. With just 2% having faith or trust in political

parties, more than eight million voters turned to the M5S which pledged

to ‘clean up’ and ‘shake up’ the political system.

Consistent with its election

pledges, the M5S is refusing at this stage to form an alliance with the

PD (Partito Democratico) electoral coalition, or with the coalition of

the PDL (Popolo della Libertà), the party of Silvio Berlusconi, both of

which got around 29% of the vote. The ‘grillini’, as they are often

called, effectively hold the balance of power. While the immediate

perspectives are unclear, if any government emerges from these elections

it will be weak, unstable and short-lived. New elections are likely,

possibly within months. In that situation, the M5S could even increase

its support – it has already gone up three points in opinion polls to

29%.

A ‘movement’ not a party

Clearly, the Five Star

Movement is a key player in the Italian political arena. But what is its

character, what does it stand for and how is it likely to develop in the

future? In reality, the confused, ambiguous and fluid nature of the

movement makes it difficult to define. Grillo describes himself as its

‘megaphone’, because the M5S, which developed in opposition to the

traditional parties, is a ‘movement’ rejecting the structures of a party

and which, therefore, cannot have a ‘leader’. In actual fact, Grillo,

who co-founded the M5S with Robert Casaleggio, a wealthy marketing and

web businessman, has an enormous personal influence over the movement.

He owns the M5S ‘franchise’ and can personally decide who can and cannot

use its symbol in elections.

Grillo describes the M5S as

"neither right nor left", a "movement of ideas not ideologies", and this

is reflected in its membership, programme and electorate. The movement

is mainly one of young, educated middle-class professionals. Of its MPs

and senators, 24% are self-employed or small-business owners, 35% are

professional/white collar workers and 15% students, pensioners or

unemployed, 78% have a university degree.

The M5S votes were

geographically evenly spread and came from all political parties, both

‘left’ and ‘right’. Around 25% of its electorate had previously

abstained. Which parties its votes mainly came from varied from region

to region. In Turin, an industrial city in the north, for example, 37%

of the M5S votes came from the PD (which includes part of the

ex-Communist Party), and 20% from the ‘radical’ left. In Padua, 46% came

from the right-wing populist Northern League (Lega Nord). In Reggio

Calabria in the south, 49% came from Berlusconi’s PDL.

The movement has a programme,

voted for online by its members, but the pronouncements of Grillo in the

piazzas and, in particular, posts on his blog, the most widely read in

Italy, hold considerable weight. He also has a million followers on

Twitter. The use of the internet and social media is central to the way

in which the movement is organised, with ‘horizontal’ democracy seeking

to replace the normal ‘vertical’ forms of democratic structures of

elected committees, delegate conferences, etc. The 163 grillini MPs were

selected online, with 20,000 people participating.

Grillo launched his blog with

Casaleggio in 2005, and the first ‘friends of Beppe Grillo’ began to

discuss online and organise local ‘meet-ups’ (they use the English

word). Things really started to take off in September 2007 when Grillo

organised his ‘V.Day’ (V standing for an Italian expletive), when tens

of thousands of people queued for hours in piazzas around the country to

sign a petition calling for politicians with a criminal record to be

banned from holding office. The movement spread via internet and social

media, and the first Five Star councillors (30) were elected in local

elections in 2008. In autumn 2009, the Movimento 5 Stelle was officially

launched, going on to get more councillors elected and its first mayor

of an important city (Parma, in Emilia Romagna). In anticipation of what

was to happen later in the national elections, M5S became the biggest

party in elections in Sicily in November 2012.

Awash with corruption

The corrupt political ‘caste’

and political system are the main targets of the movement. Grillo’s

comedy routines have always had a political edge to them. In the 1980s,

he railed against corrupt politicians. In 1986, he was banned from

public TV after a joke about the then prime minister, Bettino Craxi, who

eventually fled the country to avoid charges during the Tangentopoli

scandal. Tangentopoli lifted the lid on a sewer of kickbacks and

corruption spanning the political spectrum, leading to the collapse and

disintegration of most of the main bourgeois parties. It was against

this background of political crisis that Berlusconi was ushered to

power, and the Northern League began to grow, both claiming to be ‘new’,

‘fresh’ untainted forces.

Now, once again, Italy is

awash with corruption scandals, undermining virtually every institution

from football to the Vatican. In an international corruption league

table, Italy is ranked 72nd, below Botswana, Chad and Rwanda. At

national and local level, politicians of all the establishment parties,

including the Northern League, and in particular Berlusconi’s PDL, but

also the PD, have been found guilty of, or are under investigation for,

taking bribes to give favours to friends and family members, creaming

off millions of euros of public funds to finance lavish lifestyles, and

a myriad of other charges. The idea, already extremely widespread in

society, that they have all got their snouts in the trough, that they

are all thieves, has been reinforced by these latest scandals.

This partly explains the

success of the grillini. Grillo uses revolutionary sounding phraseology

about sweeping away the current MPs, parties and political system. This

strikes a chord, especially with young people who hold the traditional

parties in contempt and see no credible, mass left/anti-capitalist

alternative among the existing parties and political formations. Fifty

per cent of under 25s voted for the M5S (67% in Sicily), and 60% of

students.

In reality, however, the

movement is proposing not revolution but democratic reform of the

existing political system. This would include cuts to parliamentary

salaries and expenses – the grillini representatives will only take half

of their salaries, possibly less. In Sicily, the remainder of their

salaries has gone to help local micro-businesses. The M5S calls for a

change in the electoral law, halving the number of MPs, and abolishing

the state funding of political parties, etc. The money saved, it claims,

would go towards financing the rest of the M5S programme. The remainder

would be financed from scrapping military spending on wars in

Afghanistan and elsewhere.

Voicing deep discontent

Before the economic crisis,

Grillo only really ever touched on two main issues: the political caste

and the environment. The problems faced by workers in the workplace,

cuts in health, education and public services were barely if ever

mentioned. Even now these economic and social issues take second place

to political reform. But the impact of the economic crisis has been

severe both on working and middle-class people. Nearly 40% of youth are

unemployed and tens of thousands of workers are on ‘cassa integrazione’

(short-time working or at home with part of their salary paid). The

overwhelming majority of Italian companies are small, often family-run

businesses struggling to obtain credit from the banks. A company closes

down every minute.

In his ‘tsunami’ election

tour of 77 piazzas, Grillo began to give voice to the deep discontent at

economic crisis and austerity. ‘Borrowing’ demands from the

anti-capitalist left, he called for the nationalisation of the banks, a

shorter working week and a ‘citizen’s income’. He spoke about

restructuring the debt and called for a referendum on the euro. The M5S

programme opposes cuts in education and supports a totally free health

system. It is against the privatisation of water and is for the

renationalisation of telecoms.

In a context where the

parties of the ‘radical left’, like the PRC (Rifondazione Comunista),

have become invisible both in struggles and in elections, the fact that

these issues are being raised and discussed is a positive development.

The PRC stood in the elections as part of a heterogeneous electoral

alliance (Rivoluzione Civile) dominated by magistrates which got a mere

2% of the vote. However, while the M5S’s reformist agenda has reflected

and channelled the anger in society, it is entirely inadequate as a

response to the crisis. Even if the political reforms were enacted and

military spending cut, it is estimated that this would provide barely €2

billion, nowhere near sufficient to finance the proposed reforms in the

M5S programme.

There are many on the left

who say that the vote for the M5S is a reactionary vote. This is based

primarily on comments that Grillo has made about the trade unions,

public-sector workers and, in particular, CasaPound, a neo-fascist

organisation. It is important that these comments and the vote for the

M5S are put into context. A distinction has to be made between Grillo,

the M5S and those who voted for the grillini.

A breakdown of the vote for

the M5S shows that some of its best results came in areas where there

have been important local struggles. In Taranto, for instance, where

thousands of workers face losing their jobs due to the closure of ILVA,

the biggest steel factory in Europe, the M5S got the highest vote of any

party. In Carbonia Sulcis, Sardinia, where miners occupied the last pit

in Italy with dynamite strapped to their bodies to stop it from closing,

the grillinis got 33.7%. In Bussoleno, Val di Susa, centre of the mass

No TAV campaign against a high-speed rail link, the M5S obtained a

massive 45%.

Undoubtedly, in the Veneto

region in the northeast, many of the grillini votes came from former

Northern League voters, including small-business owners. But some of

these would have voted for the left in the past and, as Grillo has

shown, could be won over to a programme which included the

nationalisation of the banks and low-interest credit for small

businesses.

An eclectic mix of policies

If a credible anti-capitalist

alternative had been on offer there is no doubt that many of the votes

which went to the grillini could have been channelled in a leftward

direction, as has been the experience in Greece with the rapid rise of

Syriza. But this is not the case in Italy. The historic weakness and

collapse of the left has created a vacuum which the M5S has filled

rapidly and spectacularly. This is most definitely a complicating factor

in the development of a new mass left workers’ party. But, in the

absence of a viable alternative, the vote for the M5S marked an

important break from the parties of austerity and a searching for

radical change.

The programme of the grillini

is a confused, incoherent, eclectic mix of policies reflecting its

middle-class make-up. Grillo’s comments are often ambiguous and open to

different interpretations. They also express clumsily the genuine

feelings of many middle- and working-class people. His comments on

CasaPound were not an open endorsement of fascism but a recognition of

the reality that some of CasaPound’s policies overlap with those of the

M5S (and even with the anti-capitalist left), and that some youth

attracted to fascism could be won over to the M5S. However, many on the

left interpret Grillo’s comments as being sympathetic to fascism.

The question of the character

of fascism needs to be addressed – the grillini group leader in the

lower house has also made comments revealing an ignorance of its real

nature. So do some of the comments Grillo has made regarding immigrants:

saying that Italy cannot take on all the world’s problems, and that the

children born in Italy to immigrants should not be given the right to

citizenship automatically. However, this needs to be done not by

labelling the M5S as ‘fascists’ or in a moralistic way, but by putting

forward a programme which explains how it is possible to fight for an

extension of jobs, workers’ rights and quality public services for all,

and how this entails challenging the economic base of society.

When Grillo called for trade

unions to be ‘eliminated’ because they are ‘old structures’ like the

parties, some interpreted this as an attack on unions in general.

Others, including many organised workers, saw it as a welcome attack on

the union bureaucracy, especially as Grillo said that, if the unions

were like the FIOM (the more militant union of engineering workers) or

COBAS (union of the base), things would be different. In the same speech

he went on to declare that companies should belong to those who work in

them.

This is consistent with the

grillini support for ‘direct democracy’ over a democracy which requires

intermediaries such as parties. The real issue here, however, and which

has been expressed in Grillo’s praise of workers’ participation in

Germany, is a denial of class conflict and the promotion of the idea

that workers and bosses have a common interest in working together for

the good of the economy, a position which flows from the M5S’s

middle-class composition and outlook.

Conflicting pressures

In the very short term, the

movement is likely to grow both in terms of members and electoral

support. But very quickly the political and organisational

contradictions are likely to intensify, leading to its decline and

fragmentation, especially if it enters or forms a government at national

level. Some reforms will be possible. In Sicily, the grillinis have

blocked the building of a controversial US satellite ground station, and

the same could happen with the TAV. But the weakness of the Italian

economy and the ongoing crisis mean that these reforms will be very

limited. The movement will come under conflicting pressures from the

capitalist class, on the one hand, demanding austerity and labour market

‘reform’ and, on the other, from the working- and middle-class people

who voted for it in the hope of real political and economic change.

The limits of the M5S’s

reformist policies and the methods of the movement can be seen in Parma,

where the mayor, Federico Pizzarotti, is a grillino. As a legacy of the

previous corrupt administration the mayor inherited a budget deficit of

almost €1 billion. Already the administration has started to increase

charges for local services and impose cuts ‘because the money isn’t

there’. The grillini were elected in Parma partly in opposition to the

building of a local incinerator which, they claimed, would go ahead

‘over their dead bodies’. The incinerator has now been activated and

cannot be stopped, they say, because of the crippling compensation that

would have to be paid.

There is no concept of

building a mass campaign among local people to demand more money for

local services from central government or to stop the incinerator. While

individual councillors have recently begun to go to factories faced with

closure, and individual members are involved in local environmental

struggles, like that of the No TAV in Val di Susa, the main M5S campaign

initiatives have been limited to the question of democratic political

reform.

The absence of party

structures in the M5S means a lack of accountability and democratic

control over elected representatives, especially at a national level.

The unrest among members in Emilia Romagna and the expulsion of two

councillors, including the first ever elected M5S councillor, who

criticised Grillo for undemocratic methods, is a foretaste of future

rebellions against the political and organisational dominance of Grillo

over the movement. Already, Grillo has threatened around ten to twelve

senators with ‘consequences’ for the ‘betrayal’ of voting for the PD

candidate (an anti-mafia magistrate) for president of the Senate,

causing uproar among the movement’s members in blogland. As the

political and organisational contradictions emerge this will open up

space for discussion about the need for an anti-capitalist political

party based on the workers’ movement and on struggle.

The M5S represents a new and

important factor in a situation of political, economic and social

crisis. An analysis and understanding of the character and the

weaknesses of this movement is necessary but is not, in itself,

sufficient. Those on the left in Italy need to engage politically with

the grillini and their ideas and, most importantly, with those

radicalised workers’ and youth who voted for them as part of the process

of building a real working-class alternative to the capitalist system.