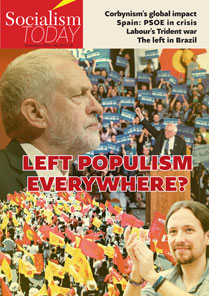

Crisis

in Spanish social democracy

Crisis

in Spanish social democracy

PSOE and the class struggle

JUAN IGNACIO RAMOS,

Izquierda Revolucionaria general secretary, explains how the

dramatic crisis in Spanish social democracy is driven by class struggle

The Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE)

is passing through its worst crisis in many decades. The ‘coup’ by

Felipe González, Susana Díaz and the party’s regional ‘barons’ (regional

leaders on the right-wing of the party, with an enormous weight in its

structures) against Pedro Sánchez, who was the party’s general

secretary, was part of a premeditated decision. It has the full support

and open backing of big capital and the financial oligarchy, and will

have deep consequences.

The breaking point, the

opposition of Pedro Sánchez and a section of the leadership to

abstaining in parliament to allow Mariano Rajoy (conservative Partido

Popular leader) to form a government, kicked off an explosive internal

war. However, the underlying context of it all is the crisis of the

Spanish social democracy, in line with the rest of Europe, as a result

of its support for cuts and its fusion with the ruling class.

The crisis had one of its

climaxes on 1 October when, in a chaotic meeting of PSOE’s Federal

Committee, Sánchez was forced to resign as general secretary.

Beforehand, Felipe González and the barons had orchestrated the

resignation of 17 members supportive of their position from the party’s

executive, in order to force the resignation of Sánchez. However,

Sánchez's refusal, and his public refusals to subordinate to the PP,

caused a great confrontation in the Federal Committee.

The victory of the coup

plotters in that meeting, by 133 votes to 107, far from leaving them

euphoric and full of confidence, has only led to greater uncertainty.

None of the questions posed in the dispute have been resolved. The

internal split in the party has sharpened, which is yet another blow to

the crisis-ridden capitalist Spanish regime. This weak victory for the

coup plotters reflects the change which has taken place in the class

balance of forces. Moreover, in recent weeks we have seen that the bid

to impose abstention of PSOE MPs in order to elect Rajoy has been met

with a solid rejection by the majority of socialist voters and

rank-and-file members.

Most significantly, the

openly bourgeois sector of PSOE has been put in an extremely delicate

position. Its brutal removal of Sánchez has situated it clearly on the

side of the PP. All the demagogy of the barons has been exposed. When

they speak of prioritising ‘Spain itself’ over their own party, they are

not talking about the millions of unemployed, the thousands of evicted

families, or the youth who have been forced to emigrate. They don’t care

about the millions of households with no income, or the workers who have

been robbed of their rights, or the public education system which is

being degraded and privatised. These politicians, who despite their

‘socialist’ membership card are in the service of the ruling class, are

really interested in guaranteeing political stability so that the PP can

maintain the cuts and austerity which the national and European

capitalists demand.

If the caretaker leadership

appointed in PSOE by the coup plotters imposes a position of allowing

Rajoy to come to power – despite presenting it as only a ‘technical

abstention’ – depriving the membership of the right to decide, the

crisis will only deepen. If this is the road they go down we cannot rule

out a section of PSOE MPs breaking party discipline and voting No to

Rajoy. However, regardless of this, a Rajoy government formed on that

basis will be marked with illegitimacy and fraud, which will hardly

serve to bring about the political stability which the bourgeoisie needs

to carry through its plans.

This option would, of course,

avoid the need to call a third round of general elections. However, it

would result in an even weaker government, openly questioned by the PSOE

rank and file, and which sooner or later will confront mass

mobilisations. The ruling class would also lose definitively what has

been a fundamental factor in Spanish capitalism’s stability over 40

years: a united PSOE capable of controlling and putting a brake on the

workers’ movement.

At the time of writing, it is

difficult to establish a clear perspective. Avoiding new elections needs

more than just the abstention of some MPs. The PP has already indicated

that it would need a commitment to guarantee the stability of the

government so that the cuts which the EU urgently demands can be passed

in parliament. Therefore it is not only a question of abstention to

allow a government to be formed, but of backing up the reactionary

agenda of the right wing, which in practice would be an indirect form of

grand coalition, as has been seen in Germany and Greece.

In these conditions we can

also not rule out elections in December. Of course, the Spanish

capitalists and European Commission fear this option, which would mean

postponing many important decisions. However, even though timing is

important in politics, the most important thing for the capitalists is

their strategic interests. Therefore, many voices are calling for

elections on 18 December to try and win a clearer right-wing majority,

with more seats for the PP and a disaster for PSOE, which would see the

biggest electoral debacle in its history. This option would represent

‘bread for today and hunger for tomorrow’.

Whatever happens, PSOE faces

the perspective of an accelerated Pasokisation – mirroring the complete

collapse of Pasok, the mass, former social-democratic party in Greece –

and internal divisions which could lead to a split in the party. This

would give Unidos Podemos (the electoral alliance of Podemos, Izquierda

Unida and other left formations in Catalonia, Valencia and Galicia) the

best possible conditions to definitively overtake PSOE.

PSOE's critical dilemma

As we have pointed out, the

fundamental cause which explains the crisis of Spanish social democracy

– in line with the rest of Europe – is its fusion with the ruling class

and its acceptance of austerity policies, applied by PSOE in government

with the greatest of enthusiasm. The electoral defeats which PSOE has

suffered since 2011, starting under José Luis Zapatero’s leadership and

continuing under Alfredo Rubalcaba, are directly related to the party’s

support for cuts and constitutional reforms in the interests of the

banks, its nauseating support for Spanish nationalism, and championing

capitalist ‘governability’.

This political strategy has

clearly situated PSOE on the right. The eruption of Podemos which won

half of PSOE’s electoral base is another clear indicator of the

fundamental tendencies in this crisis. There is a shift to the left

among the working class and youth which was expressed in an

extraordinary level of social mobilisation, not seen at least since the

mass struggles against Francoism in the 1970s. In the ‘15 May’

indignados movement, general strikes, the massive ‘march for dignity’ in

2014, and the mass movements in defence of public education and health,

mass student movement, and protests in favour of the right of

self-determination in Catalonia, millions of workers and youth turned

their backs on PSOE.

It is the impact of the class

struggle which explains the nature and brutality of the current crisis

within PSOE. It faces a critical dilemma: continue down the road of

Pasok in Greece, to become an irrelevant auxiliary force for the right

wing, or break from its subordination to the bourgeoisie and become

regenerated as a fighting left-wing force.

The possibility of taking the

latter option is far from straightforward, as the situation is showing.

The fusion of the PSOE apparatus – both its federal leadership and its

territorial regional structures – with the interests of the oligarchy

has gone very far. The huge mistakes made after the elections of 20

December 2015 have also contributed to this. Pedro Sánchez’s attempt to

lean on Ciudadanos (a new right-wing populist party) to become prime

minister – based on a pact of cuts and austerity – was a miserable

failure. Does this deal made with Ciudadanos, the ‘PP 2.0’, have

anything to do with a real government of change? Sánchez’s strategy was

exposed as a total fraud, leading to a new and more intense phase in

PSOE’s crisis.

The class struggle

The impossibility of forming

a government after the December elections reflects the depth of the

crisis of Spanish capitalism. Decades of alternation of PSOE and PP in

power have come to an end, and chronic instability in parliamentary life

has become the norm. This has wreaked havoc on the parliamentary system

– that rotten puddle of charlatans where careerists could do as they

pleased with impunity.

After the 26 June elections,

the numbers still do not add up. As we have explained in other material,

the absence of mass and sustained mobilisations against the right,

mainly down to the policy of the Podemos and major union leaders (CCOO

and UGT), was essential to the minor shift towards the right in the

elections. This has been repeated in the recent Basque and Galician

elections. However, this ‘shift’ is very fragile and mainly reflects the

electoral demobilisation of workers and youth who are demoralised by the

vacillations and ambiguities – essentially by the social democratic turn

– of the leaders of Podemos. The frustration with the Podemos-led

administrations in the biggest cities and their refusal to return to

social mobilisation is also a factor.

After 26 June, it seemed like

a government would be formed, and it was taken for granted that PSOE

would abstain when the time came. All the pressure from the start was

directed at Pedro Sánchez, to force his hand. The big capitalist media

outlets unanimously published one article after another and wrote

scathing editorials to smash any chance of a ‘no’ vote in parliament.

The bourgeoisie was delighted with the attitude of the UGT and CCOO

leaders, who seemed more anxious than anyone to bring an end to the

situation of political instability. Above all, big capital felt it could

count on PSOE and its submissive overlords to do the dirty work ‘for the

good of Spain and the party’.

Felipe González symbolises

more than anyone the fusion of the majority of PSOE leaders with the

interests of the bourgeoisie. He gave the signal to begin the savage

public attack on Sánchez, in collaboration with the media and PSOE

barons. There was no mercy for Sánchez, who became public enemy number

one, standing in the way of the ‘governability of Spain’. In the words

of El País, Sánchez was "senseless and shameless", and should be

eliminated for everyone’s sake.

Given this insidious campaign

against Sánchez, who had recently been described as "a great, moderate

and sensible leader" by the same papers, it is no surprise that his

position aroused much sympathy. However, it is not a question of

sentiments, but of politics. We must try to answer the questions: Why

did Sánchez take this path? Why did he challenge González and the

barons? How far could this clash go?

Sánchez’s resistance has,

without doubt, bureaucratic motivations – to survive as the leader of

the party. Sánchez has abundant experience in supporting neoliberal

policies, and has never failed to come out in defence of the ‘honour’ of

González, who has repaid him with a stab in the back. But these

bureaucratic motivations are not the only ones.

This clash also represents

the pressures of opposing classes, though in a distorted fashion. Those

of the bourgeoisie, which has mobilised all its resources both inside

and outside the party, and those of a wide section of the membership and

electoral base, which in turn reflects the thoughts of millions of

workers and youth. The latter want PSOE to refuse to support the PP and

to turn towards the left and rediscover the socialist programme it

abandoned decades ago. The lobbies of hundreds of PSOE members at the

party’s headquarters in support of Sánchez, and the thousands of

supportive messages on social media, are more than a symptom of this.

It remains to be seen how far

the battle will go, and how far Sánchez is prepared to go. His call for

the membership to decide whether the party abstains in favour of Rajoy,

and his position of maintaining a ‘no means no’ approach, has aroused

the sympathy of many. However, if he really wants to win the battle and

bring PSOE back as a real left force, there is only one road possible:

mobilise the socialist social base, area by area, on the basis of a

left-wing programme, against cuts and austerity, in favour of an

alliance with Unidos Podemos, and of the right to self-determination for

Spain’s oppressed nationalities.

The dynamic of the clash is

very difficult to predict. Could it end with a split, as with Oskar

Lafontaine (who left the SPD to join Die Linke in Germany in 2005) or

Jean-Luc Melenchon (who left the Parti Socialiste to found the Parti de

Gauche in France in 2008)? Could there be a fleeing of PSOE leaders

towards Podemos, as with the Pasok cadres who joined Syriza in Greece?

Could there be a Corbyn-type phenomenon? Could Sánchez abandon his

position and come to an agreement with his opponents?

All of these possibilities

are open, but following the Federal Committee’s decision and seeing the

behaviour of the caretaker PSOE leadership, it is clear that the clash

could escalate. At the same time, Sánchez has also shown signs of

weakness recently, declaring his ‘loyalty’ to the caretaker leadership

and refusing to stand up to the manoeuvres of the right-wing in the

parliamentary group.

If this split deepens, it

will find a political expression, as it already has in an incipient

fashion. It is no accident that the PSOE crisis takes place at the same

time as the crisis within the leadership of Podemos, with the clash

between Pablo Iglesias, and fellow leader Iñigo Errejón’s sector. These

differences also reflect contradictory class pressures, with Errejón on

the right and Iglesias moving towards the left, trying to reclaim the

combative language of the origins of Podemos.

Of course, the development of

a left current within PSOE would be great news. However, it is still

premature to state that this will happen for sure. Whatever the case,

all these developments show the need for organisation, struggle and the

building of a mass organisation armed with the ideas of revolutionary

Marxism, based on the mobilisation of the working class and youth to

transform society and end the dictatorship of capital. This is the task

before us, and the task which Izquierda Revolucionaria sets itself.