Capitalism’s

grave new world

Capitalism’s

grave new world

The financial crisis of

2007/08 delivered a shock to the capitalist system from which it is yet

to recover. It cut across globalisation – and the triumphalism that

followed the collapse of Stalinism. HANNAH SELL reviews an important new

book revealing the deep-rooted fears of leading capitalists.

Grave New World: the end of globalization,

the return of history

By Stephen D King

Published by Yale University Press, 2017, £20

Stephen D King is senior

economic advisor for HSBC holdings, the world’s seventh largest bank and

the largest in Europe. He clearly considers himself a sincere advisor to

the capitalists, warning them of the dangers their system is likely to

face and suggesting ways to ameliorate them. However, there will be

scant comfort to be found for those he advises in the pages of Grave New

World… the Return of History. As King explains, the end clause of the

title is "primarily a response to Francis Fukuyama’s famous claim in

1989 that we were approaching ‘the end of history’. He argued that

western liberal democracies and free-market capitalism had effectively

triumphed over all other political systems. As the cold war came to an

end it was a claim that carried remarkable resonance. Western values

were, apparently, on the verge of spreading throughout the world, thanks

somewhat to the forces of globalisation".

King argues, as is now

accepted even by Fukuyama, that this was hubris: "This is, perhaps, not

the end of history after all. Western-led globalisation is in big

trouble. We may be witnessing the collapse of the post-war international

economic and political order. What follows may eventually lead to the

re-emergence of imperial rivalries, a throwback to the 19th century. In

the short term, however, the world is likely to be increasingly chaotic.

As such, huge challenges lie ahead for the west".

King’s book is a list of

challenges faced by global capitalism with little proffered in the way

of solutions. It is for the capitalist class a horror story worthy of

the author’s namesake. From an opposite class standpoint he draws many

of the same conclusions that have been drawn by the Socialist Party not

just now but throughout the post-Stalinist era.

The intractable problems of

capitalism that King describes are multi-faceted. One central aspect is

the retreat of globalisation and the increase in tensions between nation

states. This is not new. From its inception one of the fundamental

contradictions of capitalism has been between the nation state, within

which capitalism developed, and the world market. However, as King says,

"the scale of the problem is bigger than ever before. Even as markets –

in trade, capital and labour – have become ever more globalised, the

institutions able to govern those markets have become ever more

fragmented. In 1945, when the United Nations was founded, there were 51

member nations. In 2011, the year in which South Sudan joined, there

were 193. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, there is no longer a

binary choice between what might loosely be described as US-style

free-market capitalism and Moscow-inspired communism".

Declining US power

King recognises that central

to the increased regional and national tensions facing global capitalism

is the decline of the US and, ironically, the collapse of the Soviet

Union which, in spite of its grotesque distortions, was based on a

planned economy and therefore represented an external threat to

capitalism. That forced the capitalist nation states, however

reluctantly, to work together under US leadership.

Today the US remains the

world’s greatest superpower, particularly militarily, as King explains:

"In 2014… China, the second-biggest military power, had a military

budget roughly one-third of America’s, while Russia’s budget was only

half of China’s". It is, however, a declining power, far weaker than at

its zenith in the post-war period. Even militarily there are real limits

to its power, as has been written large by it being forced to cede to

Russia in Syria.

King looks back with longing

on that era when the US was able to enforce an international framework

for capitalism which, for a period, provided a certain stability. In

essence he is arguing for the development of a new framework of global

institutions based on cooperation between the world superpowers. Yet his

whole book points out the reasons why this is likely to prove

impossible. He recognises that what existed in the past was possible

only because of the US’s strength. The Bretton Woods agreement, for

example, which provided a global financial framework by pegging

currencies to the US dollar, was based on the premise that the dollar

was backed by gold. Prior to the second world war, the US held two

thirds of the world’s gold in Fort Knox.

The period of growth for

western capitalism that followed the post-war boom from around 1950-73

was exceptional, only possible for specific reasons that eventually

reached their limits. Part of that process was the start of the US’s

decline. King writes: "One potential source of chaos from the very

beginnings of Bretton Woods was the likelihood that eventually the US

would not be able to meet its commitment to exchanging dollars for gold

on demand at the pre-established rate". According to the IMF, "in 1966,

foreign central banks and governments held over 14 billion US dollars.

The United States had $13.2 billion in gold reserves, but only $3.2

billion of that was available to cover foreign dollar holdings. The rest

was needed to cover domestic holdings".

In 1971 president Richard

Nixon abandoned the Bretton Woods system, marking the beginning of a new

era of economic crisis. Throughout the following decades the US has been

in decline but that has now reached a tipping point. After the second

world war it accounted for 50% of the global economic market. Now it is

16% while China has soared to 18%. If, and this is a very big if indeed,

China was to continue to grow at the same rate, its economy would be

three times larger than the US by 2040.

Globalisation’s limits

We have described how we now

live in a multi-polar world, where the US is forced to collaborate with

Russia and China, and the major capitalist powers are increasingly in

conflict with each other, destabilising world relations. King sums up

this process by making a comparison with George Orwell’s 1984: "Orwell

may also have offered an accurate vision of geopolitical arrangements in

the 21st century. The three empires in Orwell’s world constantly changed

allegiances so that at any point in time two are at war against a third.

As the US loses its appetite for supporting the global institutions that

have established ‘the rules of the game’, it is not impossible to

imagine that the 21st century will increasingly be characterised by

1984-style superpower rivalry".

The North Korean crisis is an

acute example of the unstable character of world relations. Faced with

the nightmare possibility of a nuclear weapons strike by the North

Korean regime, Chinese and US imperialism are managing some cooperation.

This is in spite of the obstacles, not least Donald Trump’s bellicose

posturing, which are not under the control of US capitalism.

Nonetheless, such is the extreme dysfunctionality of the North Korean

regime and the unpredictability of Trump that the horror of a nuclear

strike taking place cannot be absolutely ruled out.

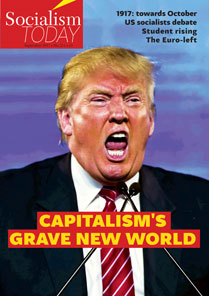

The election of Trump is both

a symptom of and a catalyst for the tendency for US imperialism to move

in an isolationist direction. This trend has been developing for some

time as capitalist globalisation has come up against its limits. Even

some of its most rabid supporters have moved into opposition. For

example, Larry Summers, former chief economist of the World Bank and no

supporter of Trump, has shifted from being an uncritical cheerleader for

globalisation to calling for ‘responsible nationalism’.

There is no solution for

capitalism in retreating behind national borders, or even to regional

blocs. What is more, there are real limits to how far the enormous

integration of the world economy that has taken place in recent decades

can be unwound. No trend under capitalism is ever carried through

completely to its conclusion. Even so, King is accurately describing a

real movement in an isolationist direction.

That was abundantly clear at

the recent meeting of the G20. Capitalist commentators described it as

the most important meeting for eight years. Whereas they look back at

the meeting in 2009 as a great success, this one was condemned as an

utter failure. The presence of Trump meant that, for the first time,

there was not even a token agreement to avoid protectionist measures. It

was Xi Jinping, on behalf of China, who stepped in to posture as a

‘responsible leader’, arguing for global cooperation. Unlike US

imperialism in the past, however, the Chinese regime is not a strong

enough power on the world stage to be able to enforce its views on

others. Nonetheless, it is attempting to step into the vacuum left by

the US’s retreat under Trump, as shown by its volunteering to take the

US’s place in the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Full-blown crisis delayed

In contrast to the failure to

agree anything this year, when in 2009 the major powers faced the worst

economic crisis since the great depression of the 1930s, they cooperated

to rescue the financial system, pumping vast sums into the world economy

to ameliorate the worst effects of the crisis. Yet none of the

underlying problems were solved. King says: "True, the G20 members

collectively managed to avoid another great depression. They did not,

however, return their economies to the growth rates of old. The recovery

in economic activity in the western developed world was, by historical

standards, unusually limp".

King points out that the

cooperation actually contained large elements of competition in the form

of using quantitative easing to implement a kind of competitive currency

devaluation: "No one would admit such a thing – no one, apparently, was

in the business of pursuing 1930s-style ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ currency

devaluations – yet as one central bank after another fired up the

printing presses, it became increasingly difficult to think of

quantitative easing in any other way". He adds: "Put another way,

monetary policy has – unwittingly – become a mechanism by which

countries end up waging financial warfare".

King argues, along with many

capitalist economists, that more thoroughgoing global cooperation could

have done more to combat the consequences of the economic crisis. He

suggests that "those countries that can easily sustain their debts or

reduce their savings should be encouraged to maintain – or even increase

– their spending, even as others take a more austere path. In a

post-financial crisis world, three countries were in a good position to

do so: the US, China and Germany".

He goes on to bemoan the fact

that, "of the three key players, however, only China delivered this

outcome. The Middle Kingdom’s balance of payments surplus dropped from

its 2007 peak to a mere 1.6% of national income by 2013, rising modestly

thereafter". There is no doubt that the actions of China did lessen, or

to be more accurate delay, the full consequences of the economic crisis,

particularly for a number of the major commodity producing countries.

This was only possible because China is still not a ‘normal’ capitalist

country, as King recognises, but because of its history still a peculiar

kind of ‘state capitalism’ which was able to pump credit into the

economy on a monumental scale. This in turn has produced a ratio of

state debt to GDP of 270% which under a ‘normal’ capitalist regime would

have already caused a major collapse. As it is, growth in China has

slowed and many of the countries it sustained in the years after

2007/08, such as Brazil, are now in devastating economic crisis.

This is a precursor to a new

stage of global economic turmoil that will be posed at a certain stage.

King has no policy proposals to prevent this. When he touches on the

reasons for the 2007/08 crisis and the weak recovery since, he gives

many of the same explanations as Socialism Today. Explaining what

2007/08 revealed, he writes: "So what was hiding behind the curtain? The

pace of economic growth was much slower than had previously been

assumed. For most countries in the developed world, the rate of increase

in living standards had begun to slow long before the onset of the

financial crisis. The crisis itself – and its aftermath – simply

reinforced the point".

‘Socialism’ for the rich

He adds: "The idea that

international free-market capitalism has delivered the best outcome for

all is less than compelling. Take, for example, the US economy. On

average, living standards appear to have risen a long way since

president Reagan took office in 1980. Gross domestic product per capita

– an overall measure of living standards – almost doubled between 1980

and 2015. The distribution of the overall gain, however, has been

heavily skewed in favour of those who were – for the most part – already

well-off. The median weekly salary for full-time employees has barely

budged in real, inflation-adjusted terms since 1979 – the year before

Ronald Reagan came to power. For men, salaries in real terms have

actually declined by over 7%".

He links this to the process

of globalisation: "Yet income and wealth inequality in some parts of the

western world are, once again, on the rise, both pre- and post-tax, and

both pre- and post-benefits. The usual fiscal checks and balances no

longer seem to be working. There is a simple explanation. If the two

defining features of the modern era are, first, the increased

concentration of capital ownership and, second, greater cross-border

mobility of capital, it is hardly surprising that a national system of

taxation and benefits can do little to prevent the continued rise of

inequality".

On the ‘recovery’ he explains

accurately the effects of quantitative easing, which we have described

as ‘socialism for the rich’ and he describes as benefiting above all

"not so much the top 1% as the top 0.0001%". "They proved to be the

major beneficiaries of quantitative easing – the supposedly magical

monetary medicine where, in effect, a central bank purchases financial

assets in a bid to drive their prices higher, in the hope that

households and companies will spend more. The S&P 500 index peaked

before the global financial crisis at 1,557. It then plummeted to a low

of 683. A handful of years later – partly in response to sustained

pump-priming from the Federal Reserve – the index had jumped to a new

high of 2,270. Given that around 90% of the total value of financial

assets in the US is owned by the top 10% of households, this was –

particularly for the very well off – a very pleasant windfall gain".

"Quantitative easing may have

been designed to kick-start economic growth, but the pace of recovery in

the US – and elsewhere – was unusually weak. In particular, despite

strong gains in equity markets, companies mostly remained unwilling to

invest. In many cases they didn’t need to. Subdued labour incomes –

thanks to a mixture of weak demand, technological change and competition

from cheaper labour elsewhere in the world – meant that gains in sales

revenues alone led to higher corporate profits; higher profits, in turn,

fed through to further stock market gains, even in the absence of a

recovery in the economy. For both the owners and managers of companies,

this appeared to be a case of ‘heads I win, tails you lose’, triggering

much gnashing of teeth and, not surprisingly, a renewed interest in the

causes of, and cures for, rising income inequality".

Here King touches on a

fundamental symptom of this phase of capitalist crisis: historically low

levels of investment by the capitalist classes, despite sitting on huge

cash piles. He makes a similar point elsewhere: "In particular, although

stock markets made impressive gains in the years after the financial

crisis, capital spending in the developed world remained largely

moribund". In other words, capitalism globally is largely failing in its

‘historic mission’ of investing in developing the productive forces:

science, technique and industry. It is not doing so because there is

insufficient money-backed demand for the goods it is already producing

with current industry.

King raises the prospect that

this problem will become worse not better in the coming period. He

suggests that there could be a growth in ‘reshoring’, bringing factories

back to the US and other economically-advanced countries as the

protectionist wings of the different capitalist classes gain influence.

However, he explains that this would not be done on the basis of

providing jobs for workers in the countries to which industry was

‘reshored’ but by "replacing cheap labour with robots", thereby lowering

wages further on a global basis.

Mass opposition

On the one hand, King

recognises that mass political opposition to such developments is

inevitable, and that both right and left populist movements are a

response to the endless austerity on offer from globalised capitalism.

On the election of Trump he correctly points out that this reflects the

enormous unpopularity of all politicians who are seen as part of the

establishment, not least Hillary Clinton: "The proportion of Americans

polled who have either ‘a great deal’ or ‘quite a lot’ of confidence in

Congress dropped from 42% in 1973 – when Gallup first asked the question

– to just 8% in 2015, an approval rating lower than for any other

institution, including banks, organised labour, newspapers, the criminal

justice system, television news and big business".

King has a tendency, however,

to condemn all such movements as ‘nationalist’ without differentiating

between them. He does not properly acknowledge, for example, that the

election of the Syriza government in Greece was motivated by opposition

to the capitalist austerity being imposed by the institutions of the EU

and IMF rather than opposition to the EU on a nationalist basis.

Moreover, he overplays the

role of social media in aiding the development of new popular movements:

"It also provides a platform by means of which (let us call them)

‘disruptive’ politicians can quickly establish a meaningful voice, and

are easily able to recruit the support of like-minded people who may in

no way reflect the views of the political mainstream. No longer does the

aspiring disruptor have to go to Speakers’ Corner in London’s Hyde Park

to air his or her views before an audience of people hoping to be amused

rather than inspired. Instead, the disruptor can take to social media,

in the process bypassing the established party systems that have

traditionally acted as filters to limit the success of populists. This

leads, in turn, to the success of previously fringe movements – Syriza

in Greece, the Five Star Movement in Italy – and to the hijacking of

mainstream parties".

Without doubt social media

provides a very useful tool in building support for new

anti-establishment and anti-capitalist movements, and combating the lies

of the capitalist media. Nonetheless, social media platforms remain

controlled by massive multinational corporations. This meant that at the

height of the Egyptian revolution the state was able to shut down

Facebook and Twitter completely in order to prevent their use, although

this did not stop the revolutionary movement.

Of course social media is an

instrument which socialists should utilise, but the real reason for the

growth in what King calls ‘disruptive’ ideas are the fundamental

failings of the capitalist system which he eloquently describes. On one

level he understands this and fears the development of an effective

alternative to capitalism which would threaten its existence. This

review article, however, does not have space to elaborate all of the

potential disasters he sees ahead for capitalism.

He spends some time, for

example, looking at the likely growth of Africa’s population and the

resulting millions of young unemployed or underemployed people. He links

this to the growth of ethnic and religious violence in different

countries and raises the prospect of mass migration to Europe. Picking

out Nigeria, he writes: "Should this violence [ethnic and religious]

escalate further… Nigeria would eventually be in danger of becoming

Africa’s Syria. In the event, Syria’s refugee crisis – appalling as it

is – might end up being a mere footnote in a new epoch of mass

migration".

Ready for socialism

Lying behind all of his fears

for capitalism creating war, social collapse and mass migration is the

fear that this might lead to a search for a new society. King spends

some time on the Soviet Union explaining that, in a time of world

economic crisis in the aftermath of the Russian revolution, it attracted

millions of people worldwide because of the improvements it attained in

living standards – possible on the basis of a planned economy: "We now

know that, between 1920 and 1930, Soviet living standards rose by more

than 150%, compared with gains of 42% for Germany, 20% for the UK, and

12% for the US".

He then adds: "Soviet living

standards rose relative to those in the US in the interwar period – from

20% in 1920 to 35% in 1938, only to return to 21% in the immediate

aftermath of the second world war. They rose again during the cold war,

reaching a peak of 38% of American incomes in 1975, before falling to

31% as the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. The Soviet version of economic

progress… just didn’t deliver the goods". Whether or not these figures

are accurate, far from showing that a planned economy ‘just didn’t

deliver the goods’, they give a broad outline of the positive economic

consequences of capitalism being successfully overthrown for the first

time in Russia in 1917.

Russia was an economically

backward country left isolated and under attack from world capitalism as

a result of the failure of revolutionary movements in other countries.

In these circumstances it degenerated into a monstrous Stalinist

dictatorship. Nonetheless, as King has to accept implicitly, the planned

economy – even with a Stalinist stranglehold at the top – was for a long

period able to develop the economy more quickly than even the most

advanced capitalist country, transforming the Soviet Union into a world

superpower. Eventually, the bureaucratic mismanagement of the economy,

which always had a terrible cost for the working class and the

environment, became an absolute fetter.

Nonetheless, the fear of a

new attempt of the working class and poor to end capitalism and build a

new democratic socialist society runs through this book. Stephen D King

argues the case for a world in which nation states become historical

remnants like counties today as people choose to live together in

harmony. Yet he sees that under capitalism the opposite process is in

the driving seat as national tensions grow. He describes the technology

which capitalism has created which could, if harnessed properly, meet

the needs of humanity globally – yet which, while science, technique and

industry remain in private hands, are a catalyst for economic crisis. No

wonder he is afraid. The world he describes really is rotten-ripe for

socialism.