Greece:

workers versus capitalism

Greece:

workers versus capitalism

The elections on 6 May were a clear rejection of

austerity by the majority of people in Greece. With a re-run due on 17

June, the political establishment and international capitalists are

waging a fierce propaganda war to get the result they desire: a

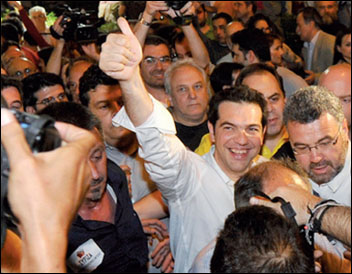

government pushing further savage cutbacks. Alexis Tsipras, leader of

the left-wing coalition, Syriza, called it "a war between peoples and

capitalism". TONY SAUNOIS (CWI) and ANDROS PAYIATOS (Xekinima – CWI

Greece) report.

THE GREEK ELECTIONS on 6 May resulted in a political

earthquake. Powerful aftershocks are still hitting the global economy,

the EU, and Greece itself. These are now set to be the precursor to even

stronger political and social upheavals.

The workers’ organisations and youth in Britain and

the EU need to extend their solidarity to the Greek workers. The

workers’ movement needs to oppose the demands that the ‘troika’

(European Central Bank, European Commission and International Monetary

Fund) and others are making for Greek workers to accept more austerity.

Such solidarity is part of the workers’ struggle in all countries

against the attacks on them by their own ruling class and governments.

The elections shattered the old established

political allegiances, but no coalition of parties from either the left

or right were able to form a parliamentary majority. The government has

been left paralysed, and new elections have been called for 17 June.

This parliamentary paralysis is a reflection of a Greek society in

turmoil. There are powerful features of revolution and

counter-revolution. Martin Wolf warned in the Financial Times: "Looting

and rioting could occur. A coup or civil war would be conceivable". (A

Permanent Precedent, 18 May)

Syriza (Coalition of the Radical Left), whose share

of the vote leapt from 4.6% to 16.78%, emerged as the second most

successful group in the elections. This tremendously positive

development, which has given hope to many workers and socialists that

something similar could take place in their own countries, has terrified

the ruling class in Greece, along with Angela Merkel, David Cameron,

Mariano Rajoy and the other capitalist political leaders. It has thrown

down a potential challenge to the troika and its austerity diktat.

The crucial question is: can this left advance be

pushed further and channelled into a bigger victory in the second

election? Will the Greek working class and its organisations embrace a

rounded-out revolutionary socialist programme? Without this it will not

be possible to resolve the crisis in Greece or begin to solve the

devastating social consequences of the austerity packages thus far

introduced.

As the elections also demonstrated, if the left

fails to meet this political challenge with the correct programme,

slogans, intensity of struggle and methods of organisation, then the

far-right can step into the void. The growth of the fascist Golden Dawn,

which emerged from the election with 6.97% of the vote and 21 MPs, is a

serious warning to the Greek and European working class. It illustrates

the threat which will emerge as the crisis deepens if the left fails to

offer a real alternative to capitalism.

The collapse of the established political parties,

especially New Democracy (ND) and the PanHellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok),

was the clearest manifestation of the overwhelming rejection of the

parties which have slavishly followed the austerity demanded by the

troika. Under ND and Pasok governments, and their outgoing coalition,

Greece has been under effective occupation from international bankers,

the ECB, IMF, and EU. The European capitalist classes have adopted a

modern version of colonial rule, appointing EU commissioners as

overseers in each government ministry.

The stooge parties of the EU have been vomited out

by the Greek people. In the last three decades, ND and Pasok garnered

between 75% and 85% of the votes in each election. Their combined vote

this time was a mere 32.02% – 18.85% for ND, 13.18% for Pasok.

Brutal attack on living standards

THE GREEK WORKING and middle classes have suffered a

brutal attack on living standards and working conditions for years. As a

result of the economic crisis and austerity packages, Greece’s GDP

(total output) will have fallen 20% from its 2008 level by the end of

2012. This is one of the largest ever falls in GDP suffered by any

capitalist country since the depression of the 1930s.

These are not cold statistics. The lives of millions

of working- and middle-class people have been shattered. The social

consequences have been devastating. Public-sector workers have seen

wages slashed by 40%. A cup of coffee costs the same in London or

Athens. Yet in Greece many workers are paid only €400 per month, a

pittance. These are literally starvation wages for many. The church

estimates it is feeding 250,000 people at soup kitchens every day.

Healthcare patients are expected to pay in advance for treatment, and

the number of hospital beds is being slashed by 50%. One hospital

refused to release a newborn infant until the mother paid the bill.

Thousands of schools have been closed down. Many tens of thousands have

fled the cities and gone back to the countryside where they can live

with families and at least get access to food.

The middle class is being destroyed, with many

becoming homeless, left to queue alongside the most downtrodden

immigrant workers at food lines and homeless camps. These camps appear

like a southern European version of the favela shantytowns of Brazil.

Unemployment has soared to over 21% – an astonishing 51% among the

youth.

The right wing, and the fascist Golden Dawn, have

tried to whip up nationalism and racism by targeting illegal immigrants,

whose numbers are estimated in hundreds of thousands. This is a major

challenge for the workers’ and left organisations. Emergency measures to

house and feed these people through the introduction of a special public

works programme should be demanded by the left: a programme not at the

expense of the Greek workers, but funded by the EU.

Workers fight back

THE GREEK WORKING class has tenaciously fought

against these attacks and each government which has enacted them. Pasok

replaced ND in the autumn of 2009, only to cave in to the diktats of the

troika by applying the most vicious attacks against the Greek workers

since the end of the civil war in 1949 – and ignoring its own promises

to the contrary. Pasok’s support then collapsed as workers rejected its

policies. The trade union leaders have been compelled, since the

beginning of 2010, to call 16 general strikes – three of them for 48

hours – by the pressure of the workers. Still, the attacks have

continued to rain down on the Greek population. The failure of the trade

union leaders to take the struggle forward led to exhaustion among

workers as one general strike followed another, appearing to lead

nowhere. Now in the elections they have vented their rage against the

pro-austerity parties.

Tens of thousands have emigrated, out of

desperation. Many more are on the waiting lists. It has been estimated

by the Greek press that there are currently 30,000 illegal Greek

immigrants in Australia alone. Some have even gone to Nigeria and

Kazakhstan, so desperate has life become.

Others, driven by desperation and the humiliation of

the plight they find themselves in, have taken a more tragic exit. The

international press featured the suicide of 77-year-old retired

pharmacist, Dimitris Christoulas, who shot himself in front of the Greek

parliament because of debt. The trigger was effectively pulled by the

troika and its policies. Having increased 22%, the suicide rate in

Greece is now the highest in Europe. One radical journalist who recently

returned from Greece witnessed a Mercedes car driven into the sea by a

small businessman who killed himself. Under Greek law debts cannot be

passed onto the family. These are conditions reminiscent of those

described in John Steinbeck’s epic novel about the US depression, The

Grapes of Wrath.

There is bitterness, hatred and anger directed

toward the Greek rich elite and their politicians who cannot safely walk

the streets or enter public restaurants. The rich are transferring their

money to Switzerland and other European countries while the mass of the

population is left to suffer the consequences of the crisis. In the

elections, the Greek people punished all those politicians and parties

which had implemented the austerity policies.

The thorny issue of coalitions

THE LEADERSHIP OF Syriza, particularly its top

figure, Alexis Tsipras, correctly took a bold stand by refusing to join

a coalition with either Pasok or ND because of their support for the

terms of the bailout and their continuing acceptance of austerity. He

offered, instead, to form a left bloc with the Greek Communist Party (KKE)

and tried to include the split from Syriza – Democratic Left – in order

to fight for a left government.

Although limited, he proposed that this left front

be based on a programme of freezing any further austerity measures,

cancelling the law which abolishes collective bargaining and slashes the

minimum wage to €490 per month, and launching a public investigation

into the Greek debt, during which there would be a moratorium on debt

repayments. This programme, although inadequate to deal with the depth

of the crisis in Greece, would have been a starting point for developing

the struggle against austerity and as a basis for a programme necessary

to break with capitalism.

Scandalously, the leadership of the KKE refused to

even meet with Tsipras – a continuation of its previous sectarian

approach towards Syriza, the rest of the left, and the trade union

movement. Syriza had correctly proposed a left front together with the

KKE and Antarsya (Anti-Capitalist Left Coalition in the elections). This

was refused. The idea of a left front of Syriza and the KKE was

something initially campaigned for by the Greek CWI section, Xekinima,

in the period 2008-10. Though viciously attacked initially, this idea

gradually developed support and was eventually taken up by Tsipras and

the Syriza leadership.

Had such a joint election list been formed it would

have emerged as the largest force and got the 50-seat bonus in

parliament which the Greek election system gives to the largest party.

Even if this was not enough to form a parliamentary majority, it would

have put the combined left forces in a commanding position to enter

second elections and to offer the realistic prospect of a left

government.

While the KKE refused to even consider joining a

left coalition government, it has been prepared to join a capitalist

coalition in the past. The KKE entered a coalition with ND in 1989. KKE

general secretary, Aleka Papriga, has argued that they have learnt from

this experience, using this to justify not joining forces with Syriza.

However, a united left front, on the basis of fighting against

austerity, is entirely different from joining a pro-capitalist

government with ND.

A working-class left front led by workers’ parties

could have served to unite in action the fragmented left forces in

Greece. It could have led to the building of a powerful, organised

movement outside parliament as a basis to challenge capitalism.

Unfortunately, other left forces, like Antarsya, also adopted a similar

attitude during the first election. However, Antarsya now faces huge

pressure from below, and sections of its ranks are demanding a united

front of some kind with Syriza in the 17 June elections. The issue is

still being debated, with the majority in the leadership wanting to

stand against Syriza. If this line is adopted by Antarsya, it will pay a

heavy price with a serious fall in its support. Antarsya won 2% in the

2010 local elections, and 1.2% on 6 May.

The sectarianism of the KKE leadership has provoked

opposition within its own ranks as well. Some party members said that

they would vote for the KKE but urge others to vote for Syriza. A

continuation of this policy is certain to increase opposition in the

ranks of the KKE, and raises the possibility of a split within it. The

KKE has paid a price for this sectarian policy. Its vote only increased

by 19,000 (1%) to 8.48% in the May election. An opinion poll for the

June election gave it 4.4%.

Despite the inadequacy of Syriza’s programme, its

clear stand against austerity and refusal to enter coalition with any

pro-austerity parties means it is strengthening its position. It is

likely to emerge even stronger in the June elections. Opinion polls have

put it on between 20% and 26%.

Tsipras has threatened not to pay the whole of the

national debt, cut defence spending, and crack down on waste,

corruption, and tax evasion by the rich. He has supported public control

of the banking system, at times implying nationalisation. He has also

spoken favourably of Franklin D Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’. It is a radical

reform programme but does not break with capitalism. However, it is a

starting point for an emergency programme of public works linked to the

need for the nationalisation of the banks and key sectors of the

economy, and the introduction of a democratic socialist plan.

The rapid electoral growth of Syriza has important

lessons for other left forces in other countries. Such organisations can

experience a rapid electoral growth from a low base when objective

conditions are ripe. They need to establish a firm and clear profile to

fight for workers’ interests to capitalise on the situation when other

political parties have been tried and rejected. The electoral success

achieved by the United Left Alliance in Ireland, especially the

Socialist Party, illustrates this.

Syriza’s refusal to join a pro-cuts coalition with

Pasok and ND, even on the basis of their promise to renegotiate the

memorandum with the troika, is in marked contrast to other left forces

and parties at this stage. In Italy, Rifondazione Comunista entered such

coalitions at the local level and consequently destroyed its support.

The Izquierda Unida (IU – United Left) in Spain, whose support grew in

the recent election, has also now wrongly joined a coalition with PSOE

in Andalucia. A continuation of this policy could erode the growth and

development of the IU.

The pro-cuts parties, led by ND and Pasok, along

with the troika, are desperately trying to turn the second election into

a referendum on membership of the eurozone and the EU rather than on

their austerity policies. They, along with the EU establishment, are

launching a clear campaign arguing that to oppose the austerity package

will mean Greece being ejected from the euro and probably the EU.

The EU and the euro

THIS IS A central issue in the Greek crisis and it

is crucial for the left to have a clear policy and programme to face up

to this question. Unfortunately, despite taking a bold stand against

austerity and coalition with ND and Pasok, Tsipras and the Syriza

leadership are not arguing for a clear alternative. In part, this

reflects the pressure of a majority of Greeks who, while rejecting

austerity, want to remain in the euro – 79% according to a recent poll.

This reflects an understandable fear of what would

follow if Greece was ejected from the euro, including the potential

isolation of Greece’s relatively small economy. The Greek masses are

terrified of being thrown back to the social conditions of the 1950s and

1960s, or the high inflation of the 1970s and 1980s. Syriza and the left

need to answer these fears and explain what the alternative is. It is

clear that Tsipras is gambling that the EU would not throw Greece out of

the eurozone because of the consequences it would have for the rest of

the EU. Yet this is not at all certain.

The KKE, on the other hand, opposes the euro and the

EU and attacks Syriza for its attitude on these issues. Politically,

this is one of the justifications it uses for not joining a left front

with Syriza. While the KKE formally speaks in very radical rhetoric

about a "people’s revolt" or an "uprising", it adopts a propagandistic,

abstract approach in practice. This is totally unfitted to the class

polarisation and willingness to struggle which currently exists. It even

justified not joining a left governmental front because, "what would

then be the character of the opposition?" Opposition to the EU and the

euro on a nationalist basis means the KKE is trapped in a capitalist

framework. What is necessary is an internationalist socialist approach

that links together the struggle of the Greek workers with the working

class in other EU countries and beyond.

It is true that a section of the European ruling

classes is terrified of the consequences of throwing Greece out of the

eurozone. The Centre for Economic and Business Research estimates that a

‘disorderly’ collapse of the euro caused by Greece leaving could cost up

to $1 trillion. An ‘orderly’ collapse would cost 2% of EU GDP – $300

billion. Such a development would have massive consequences for the

whole of the EU and could result in the break-up of the eurozone, with

possibly Spain and/or other countries breaking from it.

However, the overriding fear of the German ruling

class and others is that, if substantial concessions are made to Greece

then Spain, Italy, Portugal and Ireland would clamour for even more.

This they cannot risk. Thus, the Centre for Economic and Business

Research concludes: "The end of the euro in its current form is a

certainty".

Tsipras and Syriza mistakenly believe that it is

possible to remain in the eurozone and, at the same time, not introduce

austerity policies against the working class. Yet the euro itself is an

economic corset which allows the larger capitalist powers and companies

to impose their austerity programme throughout the eurozone.

Syriza is correct to say it will refuse to introduce

austerity. But how would it then face up to the threat of Greece’s

ejection from the euro? This is the inevitable course events are now

taking. It is not credible simply to respond by saying Greece will

remain in the euro and oppose austerity. If it did this, and a left

government was thrown out of the euro, Syriza would not have prepared

itself to answer being blamed by the right wing for this development.

While most Greeks fear being ejected from the euro

at this stage, that does not mean that the euro can or will be accepted

at any price indefinitely. Syriza needs to respond to this attack by

clearly explaining that, if we reject austerity, they will eject us from

the eurozone. Even without a government opposing austerity Greece could

be ejected from the euro.

Faced with such a situation, a left government

should immediately introduce capital and credit controls to prevent a

flight of capital from the country, nationalise all banks, finance

institutions and major companies. It should cancel all debt repayment to

the banks and financial institutions. The books should be opened to

inspect all of the agreements made with international banks and markets.

The assets of the rich should be seized and safeguards given to small

savers and investors. It should introduce an emergency reconstruction

programme drawn up democratically as part of a socialist plan which

would include a plan to assist small businesses.

At the same time, Syriza and a democratic government

of workers and all those exploited by capitalism should appeal to the

working people of Europe – especially those facing a

similar situation in Spain, Ireland, Portugal and Italy – to join them

in solidarity and begin building a new alternative to the capitalist EU

and euro. The massive crisis erupting in Spain and elsewhere would mean

that working people would rally to such a call. This could be the first

step to the formation of a voluntary democratic socialist confederation

involving these countries as a step towards a socialist confederation of

Europe. Such a process should be begun now with direct links being built

with the left and workers’ organisations in these countries.

Unfortunately, a failure to boldly answer the threat

of being ejected from the euro will only serve to partly disarm the

movement against austerity. It may prevent Syriza from emerging as the

largest party. The Greek ruling class and the troika are campaigning to

make the election about membership of the euro, not about austerity.

They are attempting to terrify people out of voting for Syriza and to

rally fragmented right-wing voters around ND – as well as from the

right-wing parties that failed to enter parliament. However, after years

of austerity measures and brutal attacks it is not certain this strategy

will succeed.

Despite Syriza’s weakness on the EU and euro, at the

time of writing it seems certain to increase its support and has a

serious possibility of becoming the largest party in close competition

to ND. Recent polls have put both parties at between 20% and 23% of the

vote.

New phase of the struggle

SHOULD SYRIZA EMERGE in the lead or at the head of a

government this would not signal the end of the crisis. Nonetheless, it

would begin a new phase that the workers’ organisations need to urgently

prepare for if they are to take the struggle forward. Syriza needs to be

strengthened by workers, youth, the poor, and all those opposed to

austerity joining its ranks and getting organised. Syriza, as a

coalition, is now attempting to broaden out to begin including social

movements and organisations.

Tsipras has rightly called for the left to come

together in a united front. This needs to be given a concrete, organised

expression through the convening of a national assembly of rank-and-file

delegates from the left parties, trade unions, workplaces, universities,

neighbourhoods and community organisations. Local assemblies of elected

delegates from these same spheres should be urgently formed under the

initiative of Syriza to prepare for the coming struggles and to ensure

that a future left government carries out policies in the interests of

working people.

The ruling class is beginning to feel threatened by

the emerging challenge of Syriza and the left. There is the threat of a

collapse in society if the left does not seize the moment. Government

funds may even run out before the election on 17 June.

Although in a different era, there are some

parallels between the situation in Greece and that which developed in

Chile 1970-73. There are also many parallels with developments taking

place in Latin America today in countries like Venezuela, Bolivia, and

Argentina. In Chile 1970-73, a massive polarisation developed in

society. The right wing and ruling class prepared their forces – they

could not allow the impasse to continue. The fascist organisation,

Patria y Liberdad, marched, bombed and attacked local activists and

acted as an auxiliary to the military which struck in a deadly coup on

11 September 1973.

Golden Dawn, which praises the former Greek military

dictatorship and Hitler, can act as a fascist auxiliary should the

ruling class, or sections of it, conclude they have no alternative but

to ‘restore order’ through military intervention. Although this is

unlikely to be the first recourse of the ruling class, it could

eventually move in this direction. If Golden Dawn’s support declines –

as the polls indicate it will in this election – it would be positive,

but it would not be the end of the threat posed by this fascist

organisation.

Its leader, Nikolaos Michalokiakos, threatened those

who have "betrayed their homeland… the time has come to fear. We are

coming". It cannot become a mass force in its own right but, like Patria

y Liberdad in Chile, it can become (and already is) a vicious

organisation that can act as an auxiliary to attack minorities and the

working class.

Golden Dawn is sending its ‘black-shirt’ thugs to

attack immigrants who suffer daily beatings and threats from them.

According to press reports, in Gazi, Athens, it left leaflets outside

gay bars warning they would be the next target, and attacked gay people

leaving the bars. This poses the urgent necessity of forming local

anti-fascist assemblies that should establish groups to defend all those

threatened by fascist attack.

Being pushed further left

IN THE ELECTION, if Syriza emerges together with

other left forces to win a parliamentary majority, a left government

headed by Syriza and Tsipas could be pushed rapidly towards the left

under the pressure of the mass movement and depth of the crisis. This is

also a fear of the ruling class. Such a development would also set an

example in other countries such as Spain and Portugal.

A government of this character could at some stage

even include features of the Salvador Allende government in Chile

1970-73, as well as some from the governments of Hugo Chávez, Evo

Morales, and Cristina Kirchner in Venezuela, Bolivia and Argentina. This

could include taking measures that attack capitalist interests,

including widespread nationalisations. While, at this stage, Syriza and

Tsipras are not speaking of socialism as an alternative, this could

change. In an interview in The Guardian, Tsipras said it is "war between

peoples and capitalism". (19 May)

This represents a significant step forward but

illustrates how he and the Syriza leadership could be pressured by the

situation to go even further to the left. When first elected to power in

Venezuela, Chávez did not make reference to socialism. Such a scenario

in Greece is not at all certain but cannot be excluded at a certain

stage. Particularly under the impact of the deepening crisis and class

struggle, demands like nationalisation, and workers’ control and

management, can be embraced by wide sections of the working class.

Should the pro-cuts parties be able to cobble

together a coalition – on the basis of ND becoming the largest party and

gaining the 50-seat bonus – then it would lack any credibility,

authority or stability. Any such parties forming a government with such

low levels of support would effectively constitute a coup against the

majority of the Greek people by minority pro-austerity parties. They

would face intense anger and bitter struggles by the working class. Such

a government would face the huge anger of society and a ferocious

struggle of the workers to get rid of it, particularly as they will see

the powerful possibility of a left government around Syriza, which

would, under these conditions, be the main opposition force, deepening

its presence and roots in society.

In this situation, Syriza should prepare a struggle

against the government and the capitalist system. Xekinima, the Greek

section of the CWI, would propose that, under these conditions, the

central slogan should be for a struggle to bring these institutions down

through strikes, occupations and mass protests.

The rapid growth of Syriza is an extremely positive

development. However, the depth of the social and political crisis

unfolding in Greece will put it to the test along with all political

forces. If it does not develop a fully rounded-out programme, set of

methods, and approach of struggle that can offer a way forward to the

masses, then it can decline as rapidly as it has arisen. To assist those

forces in and around Syriza in drawing the necessary political

conclusions as to the tasks needed to take the struggle forward, the

strengthening of the Marxist collaborators of Syriza in Xekinima is also

an urgent necessity.