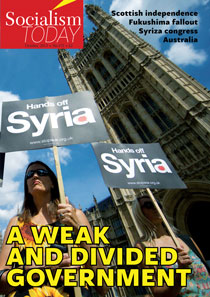

Britain’s

weak and divided government

Britain’s

weak and divided government

David Cameron has been

strutting around on the world stage, loudly demanding military action

against Syria. Yet when it came to it, he could not even get the support

of his own parliament! HANNAH SELL assesses the meaning of this dramatic

political defeat.

On 15 February 2003 up to 30

million people demonstrated against the Iraq war in more than 60

countries worldwide. Over a million demonstrated in London. The

Socialist Party argued at the time that this should have been followed

by a 24-hour general strike, which would have forced Tony Blair and co

to pull back from participating in the invasion. We also explained that,

had a mass workers’ party existed, able to give a clear voice to the

millions who opposed the war, the anti-war movement would have been

strengthened enormously. Even as it was, the demonstration shook the

government to its core, with Blair famously telling his children to be

ready to move out of Downing Street as the fate of the government hung

in the balance.

Thirteen years previously, US

president George Bush Snr had declared the ‘New World Order’. Following

the collapse of Stalinism, the US was now the only global superpower,

with military spending equal to the combined spending of the 15 states

that came after it. History, we were told, had ended and a vista of

capitalist democracy and stability opened before us, with the US acting

as the world’s policeman. But when George W Bush led the US in invading

and occupying Iraq and Afghanistan he graphically demonstrated not the

strength, but the limits to US power. As we predicted, the US-led

occupations created misery and disorder, not order, in the Middle East.

They also called into being another superpower, potentially the most

powerful on the planet, in the form of the massive anti-war movement

that swept the world.

This year the Iraq anti-war

movement has scored its first victory. David Cameron’s historic defeat

in the House of Commons on 29 August over taking part in the bombing of

Syria – by 285 to 272 votes – was a direct consequence of the invasion

of Iraq a decade earlier. So large did Iraq loom over proceedings that

in the parliamentary debate two MPs mistakenly talked about Saddam

Hussein instead of Bashar al-Assad!

The stepping back of Britain

has triggered a complete unravelling of Barack Obama’s plans for quick

air strikes against Syria. Clearly, this is not because Britain would

have had a decisive military role to play in any attack. The USA’s

military power has declined – responsible for 39% of global military

expenditure in 2012 compared to around 50% previously. Nonetheless, it

still dwarfs other countries. China comes second (9.5%), Russia third

(5.2%) and Britain a distant fourth (3.5%).

However, Cameron’s defeat

shattered Obama’s already very fragile fig-leaf of an international

‘coalition’, leaving the reality exposed that this would be a virtually

unilateral strike by US imperialism. This exacerbated the widespread

hesitation among sections of the US capitalist class, including the

military, about the dangers of escalating conflict in the Middle East

and ‘blowback’ in the US and globally. All this for a bombing which

would achieve nothing, other than maintaining US prestige following

Obama’s statement that a chemical weapons attack would constitute a ‘red

line’.

Above all, Cameron’s defeat

highlighted the unpopularity of an attack on Syria, not just in Britain

but in the US. US imperialism is terrified about reigniting a mass

anti-war movement, this time against the background of the deepest

crisis of capitalism in 80 years. More than seven out of ten Americans

and four out of five Britons currently oppose an attack on Syria.

For imperialism this raises a

real fear about the obstacle ‘the other superpower’ could be to the

prosecution of future wars. In the wake of its defeat in Vietnam, the

‘Vietnam syndrome’ severely limited the ability of US imperialism to

intervene abroad militarily. Only the attacks on 9/11 made it possible

for George W Bush to invade and occupy Iraq. But now the ‘Iraq syndrome’

has left US, and British, imperialism with extreme difficulties in

committing ground troops and even, in the case of Syria, carry out

bombing raids. It is not precluded that a missile attack on Syria could

be proposed again, further down the road. However, capitalist

politicians on both sides of the Atlantic are now very nervous of doing

so. The potential deal for Syria to hand over its chemical weapons has

offered Obama a temporary way to retreat from an attack while saving

face, but to have to be ‘rescued’ by the Russian president, Vladimir

Putin, is also a further serious blow to the prestige of US imperialism.

Political consequences

The Tory party, as the main

party of British capitalism, was once known as being far-sighted,

thinking through the consequences of its actions for decades ahead. It

is an indication of the decline of British imperialism to a third-rate

power that Cameron and co seem incapable of thinking beyond next week,

never mind the next year.

Along with France, it is

Cameron’s government which has been banging the war drums since the

start of the civil war in Syria, demanding increased western military

intervention. Stupidly, despite all the experience of Iraq, they

imagined Assad would be easily overthrown. Instead, as we warned, an

intractable sectarian civil war between the regime and insurgents has

developed, with no prospects for a quick resolution. Yet Cameron

continued to campaign for war, only to discover that he could not even

get support for air-strikes through his own parliament!

In Britain this was the first

defeat of a government over going to war since the defeat of Tory prime

minister Lord North in 1782, over the continuation of the war against

the American colonies fighting for independence. Lord North resigned a

month later. The Con-Dem coalition was already weak, facing problems on

numerous issues from Europe to Universal Credit, and has been dealt a

body blow by this defeat, yet it remains in power. A central reason for

this is the woeful role of the parliamentary opposition, the Labour

Party. Cameron was furious with Ed Miliband because Labour failed to

support the government, apparently describing Miliband as a

‘copper-bottomed shit’. However, Miliband has gained no kudos for the

defeat of the government. On the contrary, his net satisfaction rate has

slumped even further to minus 36, below Cameron’s rating!

Voters remember that it was a

Labour government which launched the invasion of Iraq and understood

that Miliband did not actually oppose the attack on Syria. He had, in

fact, initially indicated that Labour would vote for the government

motion. It was only after a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party at

lunchtime on the day of the vote that Miliband was forced to change his

mind and withdraw support for the government. Instead, Labour moved an

amendment, not opposing an airstrike on Syria but demanding "the

production of compelling evidence that the Syrian regime was responsible

for the use of these weapons". The amendment was also defeated, by 332

votes to 220. It is probable that Miliband did not realise the likely

scale of the Tory rebellion, and therefore thought the government motion

would narrowly pass without Labour support.

A comparison can be drawn

between Miliband’s stance on Syria and that of Labour prime minister

Harold Wilson towards the Vietnam war between 1964 and 1970. Unlike

Blair in relation to Iraq, Wilson was never able to commit British

troops to Vietnam, despite giving general support to the US. To do so

would have risked the potential fall of the government as a result of

huge opposition from within the Labour Party which, at that stage, still

had a mass working-class membership which was able to influence the

party via its democratic structures. By the time Blair went to war in

Iraq, however, Labour had been transformed from a capitalist workers’

party – with a working-class base albeit with a capitalist leadership –

into a capitalist party.

It would be a mistake,

however, to conclude that the Parliamentary Labour Party’s pressure on

Miliband over Syria is an indication that the party has been ‘reclaimed’

by the working class. On the contrary, the Falkirk affair has

demonstrated clearly the impossibility of influencing Labour via its now

non-existent democratic structures. It was the post-Iraq public

opposition to an attack on Syria – and a fear of the electoral

consequences of supporting it – which forced Miliband to hesitate.

Incredibly, however, the most Blairite wing of the Labour Party – led by

Blair himself – has been in open revolt against Miliband’s position.

Labour was pushed into a

stumbling and hesitant opposition to the attack on Syria. Nonetheless,

the vote on 29 August gave a glimpse of what could be achieved if the

government faced an opposition worthy of the name. Ironically, Labour’s

rare and semi-accidental defiance of the government has highlighted the

urgent need for a new mass party, armed with a socialist programme

capable of providing the working class with a powerful voice against

pro-capitalist policies both inside and outside parliament.

Miliband’s Blairite course

‘I get it’, Cameron was

forced to declare as he promised to abide by the will of parliament. If

Labour was prepared to oppose the war on the working class in Britain –

to vote against cuts in public services, to promise to immediately

renationalise Royal Mail (which would instantly scupper the government’s

plans to privatise it) and to kick the privateers out of the NHS, to

name a few – this government could have been brought down years ago.

Labour, of course, has done none of that, instead pledging to continue

with Tory austerity.

Rather than determined

opposition to the government, Miliband has concentrated on ‘standing up’

to the trade unions and the working class. Following Miliband’s woeful

speech to the TUC, the president of the PCS (civil servants’ union) and

Socialist Party member, Janice Godrich, received the biggest cheer of

the morning when she demanded to know if Miliband was prepared to oppose

austerity. His answer was unequivocal: Labour would continue with

austerity in order to appear ‘credible’. Even Frances O’Grady, general

secretary of the TUC, felt obliged to criticise Labour for supporting a

"vanilla version of austerity".

Miliband also made clear his

intention to press ahead with breaking the formal link between the trade

unions and the Labour Party, thereby destroying the final remnants of

the trade unions’ collective voice within the Labour Party. Clearly,

some trade union leaders are hoping against hope that Miliband will

retreat when faced with a dramatic cut in party funding, a point the GMB

general union has hammered home by announcing its funding to Labour will

be cut by over £1 million from January next year. However, a

‘compromise’ would make no fundamental difference.

Some of Miliband’s advisors

have intimated that a fudge could be found, such as the formal link

between Labour and the unions being broken at a special conference in

March 2014, but the current limited voting rights of the trade unions

remaining for a ‘transitional period’, perhaps beyond the general

election. Even if this was agreed, it would only prolong the full

implementation of the Labour leadership’s plans. The end result would be

the same: the final destruction of the last remnants of a collective

voice for the trade unions within the Labour Party. Given the immediate

attacks on Miliband by Cameron for being ‘chicken’, and the considerable

pressure from the Blairites to go ‘all the way’, it is still possible

Miliband will force through all the proposals at the spring special

conference.

In contrast to GMB general

secretary Paul Kenny’s clear opposition to Miliband’s proposals, when he

correctly pointed out that the trade unions have more members than all

of the capitalist parties put together, Len McCluskey, general secretary

of the Unite union, has continued to take an equivocal position.

Shockingly, he even managed to praise Miliband’s speech to the TUC,

saying he had "looked like a real leader" and was beginning to "seal the

deal with workers"!

However, among the ranks of

Unite – and all the affiliated trade unions – there is enormous anger at

Miliband’s proposals. For many thousands of trade unionists this is seen

as a defining moment from which there are only two possible outcomes.

Either the Labour leadership’s proposals are defeated, and that acts as

a springboard for a major campaign to ‘reclaim’ the Labour Party, or the

proposals are passed and the unions move to found a new mass workers’

party.

Following the experience of

Falkirk the second option is seen as more likely by growing numbers of

trade unionists, including those who have until recently held hopes that

Labour can be pushed back to the left. The Trade Unionist and Socialist

Coalition (TUSC) is doing vital preparatory work for the creation of

such a party, including its plans to stand anti-cuts candidates in

hundreds of seats in the May 2014 local council elections.

Government weakness exposed

The defeat of the government

on Syria has not only highlighted the need for a political alternative

to austerity, it has also brought home to millions the weakness of the

government. Thirty Tory and nine Lib Dem MPs voted against the

government’s motion on Syria. The Tories in the main came from the right

wing of the party. Their attitude was summed up by Tory MP Crispin

Blunt’s hope that the vote would "relieve ourselves of some of this

imperial pretension that a country of our size can seek to be involved

in every conceivable conflict that's going on around the world". The

strength of this isolationist approach, within a party which once led

the most powerful imperialist country on the planet, is another

indication of the feeble character of British capitalism today,

reflected in its main political party.

The Tory rebels are

increasingly in open revolt against Cameron and, emboldened by the vote

on Syria, are likely to come into more and more frequent opposition to

the government. Already this government has seen a number of post-war

records for rebellions, including 81 Tory MPs rebelling on Europe and

150 over gay marriage. At the same time, a section of the Liberal

Democrats are clearly trying to distance themselves from the government,

and to openly court Labour in the hope of forming a Lib/Lab coalition

post-general election. The social base of both parties is at a

historically low level. Membership of the Tories is thought to have

dropped below 100,000, and the Lib Dems below 40,000.

Even without a mass political

alternative to austerity, if the leaderships of the trade unions had

been prepared to organise a serious struggle against the cuts this

government would already be history. Their failure to do so means that

the enormous anger that exists in British society currently has no

viable outlet. At this year’s TUC congress, however, it was clear that

the pressure on the trade union leaders to act is growing. Even Dave

Prentis, general secretary of Unison, was forced to make a militant

sounding speech in favour of co-ordinated strike action. The RMT’s

motion to continue to discuss a general strike was passed, despite

behind the scenes pressure on the RMT to drop it. If the TUC was to call

a 24-hour general strike against austerity, it would get huge public

support within the trade unions and well beyond their current

membership. A movement would be created even bigger than the 2002-03

anti-war movement.

The leadership of the TUC is

terrified of calling such a strike, not least because it would conjure

into being a movement that it could not control. Nonetheless, despite

the obstacles at the top, steps towards important strike action are

taking place, including among teachers, fire-fighters and postal

workers. It is urgent that all live disputes are co-ordinated, as a step

towards a 24-hour general strike. In addition, it is important that the

whole trade union movement declares its solidarity with any trade union

or workers who are threatened with the anti-trade union laws.

In particular, it is possible

that Royal Mail management will attempt to use the anti-trade union laws

to try and prevent strike action by postal workers, which will be over

pay and conditions but also in opposition to privatisation. If they do

so, particularly given rank-and-file postal workers’ history of

unofficial action, there will be the possibility of widespread defiance

of the anti-union laws. If the CWU faces legal threats as a result, the

whole trade union movement would have to urgently come to its defence,

threatening an immediate 24-hour general strike.

There are many other issues

over which major struggles could develop in the coming months. So brutal

is the relentless driving down of workers’ living standards in Britain

that even Oxfam has warned it is unsustainable. A fight-back, in one

form or another, is coming. The Syria crisis has demonstrated to

millions how weak the government that is destroying their lives actually

is. It was defeated by the after-echoes of a mass movement that reached

its peak ten years ago. Now we need a movement on a similar scale

against austerity, but this time going beyond demonstrations and

organising both general strike action and its own political voice.