European

perspectives

European

perspectives

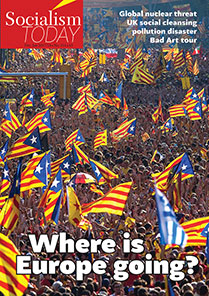

Brexit, Catalonia and the

rise of the AfD in Germany are an anticipation of even greater upheavals

to come. Analysing European perspectives for the next period, we are

carrying here extracts from a draft statement for the forthcoming

meeting of the International Executive of the Committee for a Workers’

International (CWI),

written in early November by TONY SAUNOIS.

The dramatic events that have

erupted in Catalonia and the Spanish state are a reflection of the

underlying social and political crisis gripping many European countries.

While the propaganda of the ruling class was that they had re-stabilised

and resolved the political and social crisis which unfolded in Greece,

first Brexit and now Catalonia reveal the underlying social and

political situation which exists in many EU countries. There has not

been a generalised upsurge in the class struggle in Europe, yet this

does not mean that the capitalist class faces a stable situation.

Political shocks, crises and upheavals continue to confront the

capitalist classes across Europe.

Some capitalist commentators

confidently look towards a return to substantial economic growth based

on rising levels of the gross domestic product within the eurozone in

the last quarters. However, the growth that has taken place – 2.1% this

year – has at best been sluggish and is extremely uneven. It has not

been accompanied by a rise in living standards but by continued

austerity. Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy remain gripped by mass

unemployment, in particular among the youth. Across the eurozone the

real level of unemployment – not just those officially registered –

including hidden unemployment, stands at 18%! Precarious jobs and

minimal wages, especially for young people, are increasingly the norm

throughout the EU. The slave labour scheme in Italy, which compels

students to work for no pay, is an indication of the scale of the

attacks which have taken place.

At the same time, the

underlying problem of the debt crisis has not been resolved. Apart from

a re-eruption of the Greek crisis, which is possible, there is the

possibility of a crisis unfolding in Italy should it be unable to

continue to service its public sector debt which amounts to 130% of GDP.

The Scandinavian and Nordic countries emerged relatively unscathed from

the 2007/08 crisis. However, the build-up of debt points towards them

being more dramatically affected in a future crisis which will have

important repercussions in the class struggle.

There are also major issues

developing in the European economy that will arise from the introduction

of robotics and other changes in production. In Germany there is a

discussion about the need to restructure the auto industry. The tensions

which will arise between the trade blocs was recently shown in the

conflict between the US and Canada over Bombardier which then spilled

over into Britain.

In addition to Brexit there

have been increased clashes within the EU. In the east there are

heightened tensions with Poland and Hungary. Poland is preparing to

lodge a claim for war reparations from Germany. Donald Tusk, the former

Polish prime minister, went so far as to declare that "the EU did not

need Poland and vice versa". This prompted some commentators to pose the

question of a ‘Polexit’ triggering a new crisis. There is also the

continued increase in tensions between Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia

and the EU. Putin has suffered some electoral setbacks in recent local

elections. However, his regime still retains a significant social base

of support. The opposition is mainly based on the petite bourgeoisie and

has not involved a movement of the working class, at this stage.

Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to

push for greater integration of the eurozone economies with an agreed

budget has been partly checked as Angela Merkel is compelled to draw

back, looking over her shoulder at the far-right. Further attempts to

increase eurozone integration are possible. However, how far these go is

not at all certain and they go against the grain of the centrifugal

features currently at work. This will lead to further conflicts within

the EU and the eurozone. Sections of the German ruling class are

concerned that they would have to foot the bill for a more integrated

eurozone, something they are not prepared to do.

Revolution and counter-revolution in

Catalonia

The upheavals in Catalonia

have included elements of revolution and counter-revolution. They have

also revealed the importance of the national question for the working

class and revolutionary Marxists, and exposed the crisis of leadership

which exists. Such dramatic events are a test for all left and socialist

organisations, especially for revolutionary Marxists. The comrades of

Izquierda Revolucionaria and the CWI have correctly defended the

right of the Catalan people to decide their future. We demanded a

socialist republic of Catalonia, fighting together with the working

people of the rest of the Spanish state to oppose the ruling class and

Partido Popular (PP) in a common struggle to establish a voluntary,

democratic socialist confederation of all the peoples of the Spanish

state.

This is in marked distinction

to the treacherous role played by PSOE. The leadership of Izquierda

Unida (IU) and the Communist Party has been lamentable as they have

abandoned the defence of the right of self-determination for the Catalan

people. This has more recently been echoed by Pablo Iglesias who has

removed the leadership of Podemos in Catalonia and threatened to expel

the one member of the Podemos-linked parliamentary group in Catalonia

who voted in favour of declaring independence. The nine other Podemos

deputies all voted against. This has opened up a crisis inside Podemos.

At the same time, the left-nationalist CUP has failed to fight for an

independent political programme and role for the working class and has

wrongly propped up the bourgeois nationalist PDeCat government of Carles

Puigdemont.

In varying degrees, these

mistakes by the Catalan left and the left in the rest of the Spanish

state have been echoed by others internationally. At the same time, the

pro-independence SNP in Scotland, along with Irish prime minister Leo

Varadkar, have not been prepared to support Catalonia and to oppose the

stance of either the EU or PP government. The vicious reaction of the PP

government and its determination to crush the independence movement has

alarmed sections of the ruling classes throughout Europe who fear that

the conflict could spiral out of control and open a major crisis

throughout the EU. However, this did not prevent the EU, especially the

‘three Ms’ – Macron, Merkel and May – from backing Mariano Rajoy in

declaring the referendum illegal.

The brutal response of Rajoy

reflects in part the composition of the state machine and the PP in the

Spanish state. There is a powerful Francoist legacy and tradition which

was never purged following the transition in 1978. This includes

extremely repressive, bonapartist elements. This is combined by a fear

of the consequences of Catalan independence. Catalonia accounts for more

than 20% of Spanish GDP and exports. Moreover, if Catalonia were to

separate then the Basque country could follow.

Puigdemont and PDeCat have

demonstrated their fear of mobilising the masses in a real struggle

against the PP and for independence. They have demonstrated the

incapacity of these bourgeois nationalist politicians to lead an

effective fight. Puigdemont and five ministers fled to Belgium, ‘home’

to the EU which opposed their declaration of independence and backed the

PP government. Puigdemont then appealed to the same EU to intervene and

support the independence movement!

Above all, the Catalan

bourgeois politicians fear the prospect of an independent movement of

the working class which would be necessary to defeat the repression

being served up by the PP. The repression and arrest of some of the

Catalan government will, however, boost their standing for a period. The

Spanish state has lost all legitimacy in the eyes of millions of

Catalans especially the youth. This will have serious consequences for

the ruling class in the coming period.

The importance of the national question

The national question is of

vital importance for the workers’ movement. Marxists defend the right of

self-determination and the unity of all sections of the working class.

While not capitulating to bourgeois nationalism, it is important to

recognise that within national independence movements are often

contained an ‘immature Bolshevism’. Each national question is very

concrete and it is necessary to analyse each specific situation in

determining our exact demands and slogans.

As we have seen in Scotland,

support for independence can wax and wane. We need to take this into

account in the demands we advocate at each stage. A mistake on the

national question can have devastating consequences, as has been seen

historically. Jeremy Corbyn’s wrong approach on this issue in Scotland

was a major factor preventing Labour making important gains there, and

which ultimately resulted in Theresa May being able to form a government

at the last election in Britain. This was despite the fading illusions

in the SNP as it has carried through cuts in Scotland bringing it into

collision with sections of the working class.

The repressive response of

the PP government undoubtedly increased support for independence in

Catalonia although it is not certain a majority would support it at this

stage. However, in both Scotland and Catalonia it was correct for us to

side with the most combative youth and layers of workers who support

independence, even when this was a minority – as in Scotland in the 2014

referendum. They represented the most combative layer and broadly

indicate the line of march, with ebbs and flows along the way.

In Catalonia it is important

to win the mass of the working class to support independence. This can

only be done by explaining a clear opposition to austerity and the need

for a socialist republic of Catalonia. It is necessary to explain that

an independent socialist Catalonia would enshrine the democratic and

cultural rights of all. This is also important to answer the propaganda

of the right wing in the rest of the Spanish state which is attempting

to split the people in Catalonia – and to assuage the fears of those

opposed to independence in Catalonia – especially those who migrated

there from the rest of the Spanish state.

The events in Catalonia and

the Spanish state are likely to evolve in the short term with many

contradictions and complications arising mainly due to the lamentable

role of the left – IU and Podemos, and the failure of the CUP to adopt a

position independent from Puigdemont. The right wing around the PP and

Ciudadanos has launched a ferocious Spanish nationalist campaign which

the bigger left organisations in the Spanish state and Catalonia are not

countering. It remains uncertain how these events will develop but they

signify a turning point in the Spanish state with repercussions for the

whole of the EU.

Historic crisis in Britain

This is unfolding alongside

the EU’s other major crisis triggered by Brexit. May and her government

have managed to stumble on from crisis to crisis since her election

‘victory’ – where the winners lost and the losers won! The crisis

gripping the Conservative Party is historic. It has been split into

bitter factions over Brexit. A split similar to that over the Corn Laws

(free trade) in the 19th century is a strong possibility. This was one

of the oldest and most successful parties of the ruling classes anywhere

in Europe or possibly globally. At one stage it had a large social base

– up to three million members – including among sections of the skilled

working class. This has now been reduced to a rump, with a claimed

membership of approximately 100,000 – with an average age of 71! May (or

Maybot, as she is known) has little or no authority and remains prime

minister on sufferance.

The two factors allowing her

to stagger on are fear of an electoral slaughter of the Tories and the

victory of Corbyn, and the absence of a serious alternative Tory party

candidate to replace her. This is a reflection of the long-term decline

of British imperialism and sums up its parlous state.

Corbyn’s ‘victory’ at the

last election has temporarily served to demoralise the right-wing

Blairistas in the Parliamentary Labour Party. However, they still have

control over the party machine and the overwhelming majority on city

councils. In the local councils the Blaristas continue to carry out cuts

and austerity measures which Corbyn refuses to publicly attack in order

to maintain ‘party unity’. The Blairistas nationally are waiting as a

fifth column to sabotage and undermine a Corbyn-led government should he

win the next election. The party remains two parties in one and its

character is unresolved, as we have explained previously.

New left parties

The majority of the forces

involved in Momentum and the Labour Party have many of the features and

characteristics of the new left parties which have emerged in other

European countries. While Podemos has won the support of young people

and important layers of workers, especially younger sections of the

working class, it has also included big layers of the radicalised

petit-bourgeois youth. The Bloco de Esquerda (Left Bloc) in Portugal

lacks a consolidated base among the industrial working class. Its

membership is largely among young ‘precariat’ workers and

petit-bourgeois youth. Momentum in the Labour Party in Britain is

largely composed of petit-bourgeois layers.

This does not detract from

the importance of these developments. In France, for example, the

existence of France Insoumise around Jean-Luc Mélenchon is an important

factor in the explosive situation unfolding there. However, they are not

the classic mass workers’ parties that have existed historically. They

are not yet comparable even to the PRC in Italy at its peak which had a

much stronger base among the metal workers and other layers of the

working class for a while.

The mixed class composition

of these parties is reflected in the programme and ideas they defend

which are not yet of a classic reformist or left reformist character,

with little or no reference to socialism. Even Corbyn, with the most

‘left’ posture at this stage, does not generally raise the question of

socialism. One of the tasks of the CWI is to explain the need to oppose

capitalism as a system and raise the idea of socialism as an

alternative. From a historical perspective, Corbyn’s programme is to the

right of left reformists like Tony Benn in the 1970s/80s. It is a

measure of how far things have swung to the right and how political

consciousness was thrown back that this classic moderate social

democratic programme seems so radical to the new generation.

In reality, the ruling

classes do not fear the programme of these new left parties. What they

fear is the massive pressure they would come under from the masses to

adopt more radical measures. This is not a static process and more

radical left-reformist or even centrist programmes and leaders will

develop at a certain stage. Leaps forward in this process can take place

under the impact of a renewed capitalist crisis combined with the

experience of the masses in struggle.

The crisis of capitalism

means that they are reformists without reforms. This does not mean that

the ruling class will make no concessions when confronted with a

powerful revolutionary movement of the working class that threatens

their existence. However, the era of lasting reforms under capitalism

has long passed. This is reflected in the timid and limited nature of

the programme defended by these modern day ‘reformists’ at this stage.

One of the consequences of

the economic crisis of 2007/08 was a devastating assault on the middle

class in many countries. This has very dangerous implications for the

ruling class in undermining its social base. A significant section of

these former petit-bourgeois layers have been radicalised to the left

which is a positive development. Sections, like the junior doctors in

Britain, have entered into important struggles adopting the methods of

more traditional sectors of the working class. However, the inexperience

and semi-petit-bourgeois character of this layer is also reflected in

the makeup of big sections of these ‘new left’ parties and

organisations.

New lefts’ programme

The attacks on the middle

class have also been accompanied by other important developments. There

has been a strengthening of authoritarian methods by the capitalist

state apparatus. This has been reflected by the degree of repression

used in Catalonia, Germany, Britain and other countries against

demonstrations and protests. At the same time, in some countries like

Britain, the part-privatisation of the police and cut-backs have led to

widespread discontent, even a certain left political radicalisation

among sections. This was reflected in opposition to the Tories from a

section of the police in the British election campaign.

The threat of a de facto

strike of the police in Ireland was further evidence of this. In

Ireland, our comrades have taken up the cause of the appalling pay

levels for rank-and-file soldiers. This has resulted in us winning

widespread support, including receiving letters from troops. These

developments within the state machine in the medium term are extremely

dangerous for the ruling classes of Europe and will give the workers’

movement the opportunity to at least neutralise parts of it.

The programmatic weakness of

the new left parties partially reflects the consequences of the collapse

of the former Stalinist regimes and the throwing back of political

consciousness. In addition, the fact that the working class has not yet

moved decisively to take hold of these parties and shape them as a

political instrument of class struggle. This was an important aspect of

the Greek crisis. While workers had voted for Syriza they had not joined

it and fought within it.

These features point to these

organisations being extremely unstable with an uncertain future,

especially when tested in great historic events such as Greece, Brexit

and now Catalonia. The collapse of the PRC in Italy, which had a more

solid active layer of industrial workers, is a warning of the

limitations of the new parties. The failure of the PRC – and its

eventual collapse – is one of the main factors leading to the difficult

and complicated situation which exists in Italy.

Recent experience – in

Momentum where our comrades have been excluded, the Left Bloc with a

renewed witch-hunt against our comrades, the actions of Iglesias in

Catalonia – has shown that the leadership of these parties can resort to

bureaucratic methods when faced with opposition from the left,

especially from Marxists.

The failure of the new left

parties to offer a strong alternative to the pro-capitalist parties has

in some countries allowed the far-right to make significant gains and

capitalise on the concerns among layers of workers and the middle class

about immigration. The unexpectedly larger gains made by the AfD

(Alternative for Germany) in the recent elections reflected this. Maybot

in Britain was not the only victor in an election to emerge

substantially weakened. This also applies to Merkel.

The historic demise of the

Conservative Party in Britain is being echoed in other countries. The

boss of the giant Siemens corporation described the elections in Germany

as "a defeat of the elites". Twenty percent of AfD’s support came from

people who had not voted previously. However, this will not stop any new

government, whatever its eventual composition, from pursuing further

‘liberalisation’ – additional attacks on the working class and youth.

Decline in support for social democracy

Meanwhile, the ‘social

democrat’ SPD saw its vote fall to its lowest percentage share since the

early 1930s. That was the price of joining Merkel’s coalition and the

role of the party in initiating the attacks on workers especially under

Gerhard Schröder. The decline of the SPD’s electoral support is an

important feature of this period especially among the youth. It has been

reflected elsewhere: the electoral slaughter of the French PS, which

lost 90% of its seats in parliament; the decline of PSOE, which has lost

half of its vote since the crisis in 2007/08; the prospect of the Irish

Labour Party losing all of its seats at the next election; the decline

of the PS/SP in Belgium; the collapse in support for Pasok in Greece.

Even in Austria, while the SPÖ held onto its overall vote share, it only

received 17% of votes from those aged under 29, and from 19% of manual

workers – an extremely significant collapse.

Sections of the new left

leadership are attempting to revive ‘social democracy’ from the ashes of

its decline. Yet they are attempting this in an era of capitalist

decline and decay when there is no room for the reforms conceded for a

protracted period in the past. They are reformists without lasting

reforms. They see their programme as a means of ‘reforming capitalism’

to end its neoliberal phase and introduce a more humane form of the

market. Left advisers like Paul Mason in Britain make this explicitly

clear. This will lead the new left leadership to rapidly betray the

aspirations of the masses when or if they come to power and face the

constraints and crisis of capitalism.

This was graphically shown in

Greece with the betrayal of Alexis Tsipras. This has resulted in him

being praised by Donald Trump following his recent visit to the US and

the announcement that the Greek government is buying US fighter jets!

The hopes in the German SPD that it could recover under the leadership

of Martin Schultz, who would ‘do a Corbyn’, slumped as he backtracked on

his hints at a more radical turn to the left. In Spain, Pedro Sánchez

and the movement which developed around him in PSOE crashed against the

wall of the mass movement in Catalonia. The possible radicalisation and

split in PSOE seems to have evaporated.

The decline of social

democracy is not uniform of course and there are exceptions. The Labour

Party in Britain has seen a large increase in support and membership,

for the reasons explained around Corbyn. In Portugal, the PS remains

relatively popular. It is propped up in power by the Left Bloc and the

CP and, while continuing with cuts, it has carried them out more

selectively. Coupled with the idea of a shallow, ephemeral economic

upturn, there is a certain sense that at least ‘we have not been crushed

like the Greeks’. This mood can rapidly change especially with the onset

of a renewed economic crisis or more cuts being made by the government.

Gains by the far-right

The CWI has recognised the

threat of the growth of the far-right in some countries. Often this has

been achieved on the basis of right-wing populist ideas, sometimes – as

in the case of France – demagogically stealing from the traditional

policies of the socialist left to win votes. In Germany, the AfD played

down its most ardent neoliberal policies.

Although the AfD is not yet a

consolidated political force it may emerge to be so as the Vlaams Belang

in Belgium or the Front National in France. However, such parties are

limited in how far they can go. They can rapidly go into crisis when

they face obstacles or set-backs. This has been seen in the FN following

the recent presidential election. Nonetheless, in the absence of

powerful mass workers’ parties the existence of such parties is now

established as a permanent or semi-permanent feature in Europe. This is

illustrated by the FPÖ in Austria which will need to be challenged by

new mass parties of the working class. The fact that the FPÖ won the

support of 59% of manual workers shows the alienation that exists and

the concerns of this layer particularly following the refugee crisis.

The forces of the CWI have a

crucial role to play in intervening to defend the rights of immigrants,

opposing racism and fighting for workers’ unity and in addressing the

fears and concerns of many workers. The threat from the far-right will

also produce a backlash, especially from the youth, as has been seen in

Germany. The tremendous demonstration of 20,000 in Gothenburg against

the fascist NMR, in which the Swedish CWI section,

Rattvisepartiet

Socialisterna, played a decisive role, was an illustration of this.

Sweden has remained relatively unscathed by the economic crisis of

2007-08. However, the constant jostling and realigning of parties, and

an increase in quite determined social struggles, are indications of the

convulsions to come.

The coming to power of the

right-wing, populist nationalist parties in some countries of central

and eastern Europe is a warning of the threat which these forces can

pose. For example, the extreme nationalistic rhetoric and bonapartist

measures adopted by the Law and Justice government in Poland. Yet its

attacks on democratic rights and attempts to shackle the judiciary have

provoked a backlash. At the same time, it has introduced some social

reforms on child benefit, an hourly minimum wage and a pledge to reduce

the retirement age. This has enabled it to maintain a level of support

among some workers. Yet the government’s policies have provoked protests

and struggles. Significantly, the initial protests against the proposals

to tighten government control of the judiciary were initiated by the

small left forces around Razem (Together Party) and the trade union

federation, OPZZ.

The shocks which have erupted

in the past period – Brexit, Catalonia and the growth of the AfD in

Germany – are an anticipation of even greater upheavals which will erupt

in Europe in the coming period. These will include the elements of

revolution and counter-revolution as we have already seen. Through the

application of flexible and bold tactics and initiatives, the CWI in

Europe can make significant steps forward. It can assist workers and

young people entering political and industrial struggles to draw the

conclusions to take on the tasks and programme necessary to defeat

capitalism.