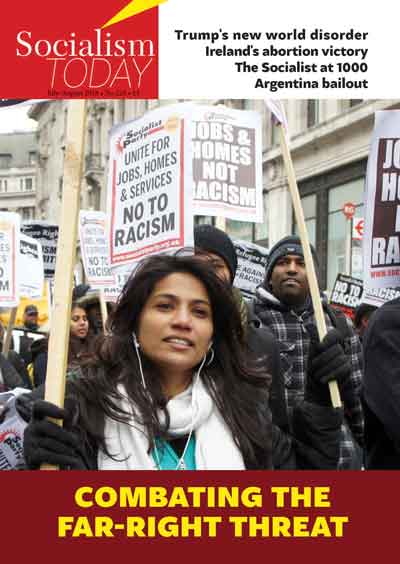

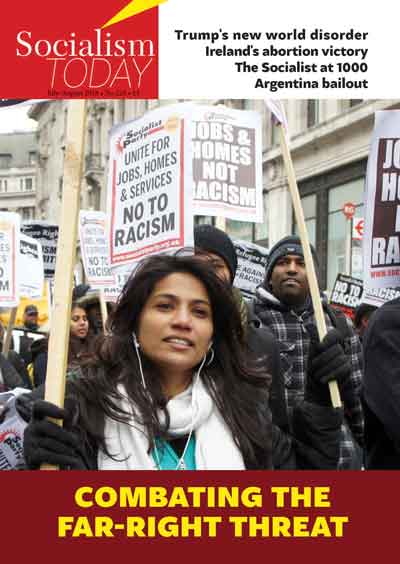

Understanding

the far-right threat

Understanding

the far-right threat

The political establishment

has been rocked in recent years – and Trump’s election, right-wing

populist gains in Europe and the Brexit vote fuel fears that the

far-right is on the rise. The dangers are real enough. However, the

potential for working-class action is often left out of the equation. As

HANNAH SELL explains, its role in combating racism and the far-right is

crucial.

Paul Stocker’s book contains

some useful facts and figures on racism, the far-right and attitudes to

immigration controls over the last century. However, for anyone looking

for an explanation of the far-right’s growth, its limits and, most

importantly, a strategy to stop it, the book falls short.

Many workers and young people

will be alarmed by the recent growth of the Football Lads Alliance (FLA)

and the Democratic Football Lads Alliance (DFLA). Based around football

gangs they have been mobilising several thousand people on various

demonstrations over the last year. On 9 June 2018 they and others

mobilised up to 15,000 to march through central London demanding the

release of the founder of the far-right English Defence League (EDL),

Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, otherwise known as ‘Tommy Robinson’. Robinson has

been jailed for contempt of court, to which he pleaded guilty. The

offence related to his reporting on a trial while it was still in

progress, as part of his campaign to whip up anti-Muslim prejudice.

Robinson has recently been banned from Twitter but, prior to that, had

200,000 followers, only slightly less than Theresa May.

The march included members of

various tiny fascistic groups but also mobilised a wider layer – angry

and alienated after a decade of austerity. It was addressed by various

figures from the populist and far-right in Britain and around the world,

including Geert Wilders, leader of the Netherlands far-right PVV party,

and Gerard Batten, the latest leader of UKIP. Steve Bannon, former

advisor to Donald Trump, sent a message of support.

The forces involved are small

compared to the numbers that can be mobilised by the workers’ movement

and the left. Last year, for example, the police estimated that 250,000

took part in the Health Campaigns Together demonstration to save the NHS,

which the Socialist Party played a central role in organising.

Nonetheless, this is the largest street mobilisation instigated by

far-right forces in many decades, and is potentially a very dangerous

development. Analysing it in order to combat it is essential.

Unfortunately, Stocker’s book is not useful for this, fundamentally

because of its lack of a class analysis.

Causes of anti-immigrant attitudes

Throughout, Stocker puts the

blame for the growth of anti-immigrant attitudes primarily at the feet

of some abstract and apparently innate ‘public opinion’. He recognises,

and gives numerous examples of, how different governments from 1905

onwards have implemented racist immigration controls but argues that

they have mainly been reacting to the pressure of their electorates. On

the post-war period, for example, he says: "Politicians sought to

maintain order and at times to stick up for the rights of migrants, yet

they were ultimately trapped within a prison of public opinion which

demanded strict controls".

More recently, he does put

more responsibility on the capitalist politicians – but for failing to

combat anti-immigrant sentiment, not for fostering it: "Politicians made

a fatal error in how they responded to anti-immigration sentiment, which

had a dramatic subsequent impact on how immigration politics was framed.

They rarely challenged the idea that immigration was a ‘problem’ and

frequently claimed to have it under control".

There is a grain of truth in

that, sometimes, different governments have felt they had no choice but

to take measures to curb immigration – even if they did not consider it

to be in the best economic interests of British capitalism. This is

because they feared the destabilising results of not doing so, including

the growth of racism and xenophobia.

What Stocker never attempts

to answer, however, is where such prejudice comes from. Clearly, there

can be a feeling that public services cannot cope with large numbers of

people arriving from another country or that wages might be lowered as a

result. What Stocker is warning of goes beyond that: an ingrained

hostility to people from other countries, particularly if they are black

or Asian. This is rooted in the capitalist system itself.

From its inception, one of

the central contradictions of capitalism has been the tension between

the existence of the world market and the fact that the system has

developed within the framework of nation states. Which of these two

contradictory trends is dominant is not fixed. We have lived through

decades in which the globalising trend has been dominant and the world

economy has become more integrated than ever before. Even so, the

world’s capitalist classes remain rooted in their own nation states,

where their wealth and power are based. In addition, the nation states

have produced deep-seated national consciousness which cannot be

overcome within the framework of capitalism.

When necessary, capitalist

classes have always been prepared to stoke nationalist feelings, for

example, to justify war, or to attempt to play the divide-and-rule card

to try and defend their rule from social uprisings and revolutions.

Without analysing them, Stocker gives examples of this, such as the use

of antisemitism by Winston Churchill and others to try and undermine

support for the Russian revolution. He also refers to the growth in

anti-Muslim prejudice over recent decades but does not draw out the link

to the propaganda used to justify the imperialist invasions of Iraq and

Afghanistan, as well as their consequences in an increased number of

horrific mass terrorist attacks.

Capitalism is now in a period

of serious crisis leading to deep divisions on the best way to defend

the system. In country after country sections of the ruling class have

turned to nationalism, searching for some means to increase the social

basis from which they can defend their rotten system. While this trend

has been developing over years, it has now reached a qualitative new

stage with the election of Donald Trump.

In Britain, the pro-Brexit

wing of the Tory Party does not represent the view of the majority of

the capitalist class and is, in the main, made up of a nationalist

section of the upper-middle class and smaller capitalists who feel

sharply how they have been pushed down by the forces of global

capitalism. They yearn for an earlier, ‘easier’ age. They also recognise

that playing the ‘little Englander’ card can give them an electoral

base, either as part of the existing Tory Party or, in the future, in a

new right-wing populist party.

What was the Brexit vote?

Stocker is particularly weak

when dealing with his central theme of analysing the Brexit vote and its

consequences. He is right to argue that the official leave campaign

whipped up anti-immigrant and racist feelings in the course of the

referendum – as did sections of the official remain campaign.

Nonetheless, he does not understand what the Brexit vote represented,

enormously overestimating the scale of the growth of racism and

nationalism that has resulted from it. The book’s conclusion is: "Brexit

and the election of Donald Trump, as well as ascendant movements on the

far-right in Europe, pose the biggest threat to the liberal democratic

order since the second world war". Brexit is considered a tipping point

in a shift to the right by society as a whole.

The strong element of a class

revolt in the referendum result is dismissed. On the one hand, Stocker

derides as ‘mythical’ the idea that there was a ‘pro-EU elite’ arguing

for remain. Yet the interests of British capitalism are best served by

remaining part of the EU and, during the referendum, 80% of members of

the Confederation of British Industry supported remain, as did the

leaders of all the major parties in Britain. A host of international

figures, including Barack Obama, were also roped in to try and win the

vote for remain. On the day after the referendum, the Financial Times,

newspaper of the capitalist class, declared: "The referendum result may

well go down in history as ‘the pitchfork moment’," by which it meant

the time when the mass of the population came for the elites.

The FT understood that

millions of workers voted for Brexit as an elemental revolt against all

they had suffered. Stocker does not accept this: "Brexit had less to do

with economic factors than cultural ones". Were the wielders of the

pitchforks motivated primarily by cultural factors, in particular,

anti-immigrant feelings? A referendum is a binary choice in which there

are bound to be all kinds of different motivations among voters on the

same side. The capitalist class campaigned in the main for remain.

However, among those who voted for it were also millions of workers and

young people worried about jobs, and people repelled by the little

Englanders of the official leave campaign.

Leave was led by right-wing

nationalists. Nonetheless, it contained a strong element of a

working-class revolt. Stocker references the Ashcroft polling conducted

just after the referendum but its central conclusions do not back his

view. Ashcroft found: "The AB social group (broadly speaking,

professionals and managers) were the only social group among whom a

majority voted to remain (57%). C1s divided fairly evenly; nearly

two-thirds of C2DEs (64%) [generally the poorest section of the working

class] voted to leave the EU".

Ashcroft also shows that

immigration was a major, but not the central, factor for the majority of

leave voters: "Nearly half (49%) of leave voters said the biggest single

reason for wanting to leave the EU was ‘the principle that decisions

about the UK should be taken in the UK’. One third (33%) said the main

reason was that leaving ‘offered the best chance for the UK to regain

control over immigration and its own borders’." In the run-up to the

referendum, anti-immigrant propaganda was being pumped out by the

right-wing tabloids. Yet it was not this that had the biggest impact but

the nebulous idea of taking control of decision making, which chimed

with people who feel they are powerless and have no control over their

lives.

New Labour culpability

That immigration was not the

first issue – given how hard it was pushed – demonstrates a resistance

to racism that exists among big sections of the population. It also

shows the potential for the working-class revolt to have been channelled

in a clearly left direction had Jeremy Corbyn been prepared to lead the

campaign for a socialist, internationalist Brexit.

This is even more the case

given that, as Stocker correctly points out, the racist and

anti-immigrant propaganda did not start spewing out of the right-wing

gutter press during the referendum but has done so over decades. He

refers, for example, to the campaign against asylum seekers which

reached its height in the first years of the century: "Between January

2000 and January 2006, 8,163 articles in the Sun, the Daily Mail,

Express and their Sunday versions mentioned the word asylum seeker. That

is, on average, just under four per day".

New Labour, in power at the

time, not only failed to counter this deluge but fed it, introducing –

according to Stocker – six pieces of legislation designed to cut the

number of asylum applicants while Tony Blair was prime minister. One

interesting titbit was how they even coordinated with the Sun:

"Journalist Peter Oborne said that he had acquired a copy of the

‘Downing Street grid’ – a timetable detailing likely news coverage of

key events in the weeks ahead used by Number 10. The grid had the Sun’s

campaign written down in advance of its launch, on the exact day in

which David Blunkett would ‘concede’ that the government was struggling

to control asylum and be quoted saying, ‘can’t argue with the Sun over

asylum’."

New Labour, like the Tories

before and after, implemented neoliberal policies in favour of the

capitalist class that undermined the living conditions of the

working-class majority. Unlike Labour in the past, which was a

capitalist workers’ party – with a capitalist leadership but susceptible

to pressure from the working class via its mass base and democratic

structures – New Labour was free to act without hesitation in the

interests of big business. This included presiding over the employers

trying to lower wages, including by exploiting workers from other

countries.

Stocker recognises that

unprecedentedly large numbers of people moved to Britain after the New

Labour government’s decision not to impose restrictions on workers

coming from the countries that joined the EU in 2004. Between 2004-08

one million workers arrived. But he dismisses the effect on wages as

‘miniscule’. During this pre-crisis period, however, wages were only

growing on average at 1% in real terms, and were declining in many

lower-paid sectors.

Clearly, the blame for this

lies with the employers who were, in the main, making fat profits while

using whatever means they could – young, agency and migrant workers – to

try and cut pay. To combat this process effectively would have required

the trade unions to organise a serious struggle to increase wages for

all workers regardless of their country of origin. In the absence of

such a struggle, concern about the levels of immigration was inevitable.

This was especially true

given the New Labour government’s cynical participation in campaigns to

divide and rule. It helped lay the blame for poverty at the feet of

those who had been forced to flee other parts of the world, often as a

result of imperialist wars backed by New Labour. The relentless

anti-immigrant campaign that has taken place over decades is bound to

have had some effect on social attitudes, given that it has not been

systematically combated by any mass force capable of appealing to the

working class. That it has not had a greater effect – at least not yet –

is testament to the degree of working-class unity that has been hard won

over previous decades.

Role of the working class

One vital factor in combating

racism has been the heroic collective struggles of black and Asian

people to defend their interests. These have been most effective when

they have been allied to the broader workers’ movement. Stocker only

mentions the trade unions once, a passing reference to the 1950s: "Trade

unions were often deeply hostile to black migrants and demonstrated

ambivalence to the racism and discrimination suffered by black and Asian

workers". This is partially true but is less than half of the story.

The workers’ movement was

also the central force in combating racism in Britain. In the 1950s, for

example, it was the railway workers’ union which played the leading role

in getting rid of the colour bar in many London pubs. This flowed from a

realisation that black and white workers had more in common with each

other than the bosses, and that the only way to stop the workers from

the Caribbean being used as cheap labour was to fight to convince them

to join the union and launch a common struggle for decent pay. In the

1970s, trade unions were instrumental in the battle to defeat the

far-right racist National Front.

It is as a result of these

traditions that black and Asian workers formed a strong bond with the

trade unions even though the majority did not come from an urban

background in their home countries. In the 1970s, black and Asian

workers played a leading role in many industrial struggles. The Grunwick

strike against low pay in 1976, which largely involved Asian women, was

one of the key battles of the decade. Even today remnants of this

remain. In 2016, the proportion of workers who were trade union members

was highest in the black or black British ethnic group.

Today, reflecting the

weakening of the trade union movement, more recent immigrants to Britain

are concentrated in the most precarious and unorganised jobs. Key to

combating low pay will be building united struggles of these workers to

fight to improve their pay and conditions. The 2017 Barts hospital

workers strike, with newer migrant workers to the fore, and the

McDonald’s, Deliveroo and TGI Fridays strikes, give a glimpse of what is

possible. Fighting for a trade union movement that launches a serious

struggle in defence of workers’ interests is still central to pushing

back racism in the modern era.

Overall racism declined

It is in large part thanks to

the historic role of the workers’ movement, plus the struggle of ethnic

minority groups for their rights, that racism has actually been

decreasing over recent decades. For example, as recently as 1995 the

British Social Attitudes survey showed that 73% of people would mind ‘a

little or a lot’ if a close relative married a black or Asian person.

When the same question was asked in 2017, 21% of people agreed.

Overall, attitudes have also

become more positive to immigration. While it is true that polls show

widespread concerns about the scale of immigration, the public outcry at

the treatment of the Windrush generation was an indication that,

particularly when faced with human beings rather than statistics, the

overwhelming majority of people are opposed to racist immigration

policies.

That is not in any way to

suggest that racist and anti-migrant views are marginal or do not need

to be combated. On the contrary, the number of race-hate crimes recorded

by the police has increased from 35,944 in 2011/12 to 62,685 in 2016/17.

On a generally upward trend, the biggest annual increase (27%) followed

the EU referendum. This fits with the experience of many black and

ethnic minority people who report an increase in racist harassment and

abuse. However, it is probably also true that another factor is a

certain improvement in the police recording of these crimes.

The figures for last year

show less than 5% of recorded race-hate crimes came into the category of

violence against the person with injury. While non-violent offences are

often very serious, they were frequently ignored by the police in the

past. Even the most serious crimes, including racist murders, were not

reliably recorded as such by the police. The fact that they now feel

under more pressure to do so is, in itself, a reflection of the

increased anti-racist mood in society.

Clearly, however, the

increased confidence of a minority to carry out racist crimes is

dangerous and needs to be combated. Moreover, while opinion polls have

shown a gradual decrease in racism over recent decades, there is no

guarantee that will continue, particularly with prominent capitalist

politicians whipping up nationalism. Nonetheless, there are important

social forces, above all the organised working class, which remain a

serious obstacle to such a reverse, provided they are mobilised.

‘Liberal democratic order’ under threat

The pessimistic conclusions

of Stocker and numerous other commentators about the growth of reaction

are not justified. In reality, their panic stems not from a rise in

racism but from the capitalist elite’s sense that events are spiralling

out of its control and it can no longer rule in the old way. Stocker

echoes this when he argues that the ‘liberal democratic order’ is under

threat.

The biggest difference

between now and the previous era is a serious undermining of the

authority of all the institutions of capitalist society, above all, of

the capitalist parties. This flows from the crisis of capitalism, for

which the working class has been paying over decades. In Britain, the

proportion of gross domestic product that goes on wages has been

shrinking for 30 years. If the share was the same today as it was in

1978, workers collectively would be taking home an extra £60 billion a

year (in today’s money). In the ten years since the world economic

crisis began, the driving down of workers’ living conditions has

accelerated dramatically, with the longest period of pay restraint since

the Napoleonic wars. This has been combined with widespread cuts,

closures and privatisation of public services.

Unsurprisingly, the parties

that have presided over that process – the Tories, Liberal Democrats and

Blairite capitalist New Labour – have all had their popular bases

severely undermined. Bizarrely, given its current incredibly fragile

grip on power, Stocker argues: "The Conservative Party, on a radical

right platform which promises to dramatically reduce immigration by

taking Britain out of the EU, is now at its most dominant in British

politics at least since the 1980s, possibly even the 1930s". Yet the

Tories were unable to even win a majority at the snap general election.

They are a party in decline, possibly terminally. In the mid-1980s the

Tory Party was estimated to have around 1.2 million members. This was

less than half its membership in the 1950s but more than ten times that

of even the most generous estimates for its numbers today.

Stocker also suggests that

the Tories are united around a ‘hard Brexit’ position. In reality,

however, they are engaged in a civil war, resulting in the government

being at constant risk of collapse. This reflects the struggle by the

overwhelmingly pro-remain British capitalist class to find reliable

political representation for their interests. The Tory Party – their

traditional choice – is no longer reliable, but it is preferable to the

even less reliable option of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership.

The far-right

Meanwhile, the Boris Johnson

wing of the Tory Party, as shown in the referendum, is happy to whip up

nationalism to try and secure a social base. Inevitably, this gives

oxygen to the far-right and potentially gives it room to grow.

Nonetheless, it would be wrong to conclude that, at this stage, the

serious strategists of capitalism want to see the growth of far-right

forces which they cannot control. Stocker correctly points out that the

capitalist class was alarmed by the growth of the British National Party

(BNP), with its neo-fascist origins, and seized on Nigel Farage and UKIP,

promoting it as a ‘safer’ protest party. Farage "had appeared on the

BBC’s flagship political debate programme [Question Time] 31 times by

2017 – making him the eleventh most regular panel member".

Far more frightening to the

capitalist class than the growth of the BNP was the fear of the growth

of a mass party of the working class with a socialist programme. The

lack of any mass working-class political representation over recent

decades has been an enormous bonus for the capitalists. It has also left

a vacuum into which right populist ideas can step. With the election of

Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party, a possible route to the

creation of such a party has been opened.

The relentless smear

campaigns against him give a small glimpse of the lengths the ruling

class would be prepared to go to in whipping up reactionary ideas in

order to try and mobilise against a socialist government. The enthusiasm

for Labour’s election manifesto in the snap election a year ago also

gives a glimpse of how a mass movement could be mobilised in support of

such a government, cutting across reaction. It is estimated that a

million of the people who voted Labour in that election had previously

voted for UKIP.

Erroneously, Stocker suggests

that the 3.5 million extra votes Labour won showed "Corbyn’s success was

indicative of the growing prominence of identity and values as opposed

to economic interest – something we witnessed during the Brexit vote".

Of course, it is true that many people from a middle-class background –

especially young people – voted for Corbyn’s programme, alongside

numerous workers who had previously broken with Labour during the Blair

era. But they did not do so primarily for reasons of ‘identity’ but

because Corbyn was promising something different to the low-paid work,

unaffordable and insecure housing, and very expensive education system

that have been all successive capitalist governments have had on offer.

Had identity or their attitude to the EU referendum been the central

issue they would have chosen another party, perhaps UKIP or the Liberal

Democrats.

Unfortunately, there is

absolutely no certainty that the start made in winning ex-UKIP voters

will continue. Consciousness is not fixed. Workers who are one day

repeating the tabloid smears about Jeremy Corbyn can vote for him the

next if they feel he is fighting for their interests. If he appears

passive or retreats in the face of the attacks of the capitalist class

and the Blairites, however, the smears can again become dominant. Look

at the situation in Derby, where the right-wing Labour group – which has

implemented massive cuts in local services – lost control of the council

in May as a result of a seat being won by UKIP. Now Rolls Royce is

making huge redundancies, with 1,500 jobs to go this year alone.

Imagine the support Labour

could gain in Derby if it was to launch a mass campaign to stop all job

losses, demanding the immediate nationalisation of Rolls Royce –

something a Tory government was forced to do in 1971 – and pledging that

an incoming Labour government would immediately nationalise it with

compensation paid only to small shareholders in genuine need. Even some

of that tiny minority of workers who are currently expressing their

anger by marching in support of Tommy Robinson could be won to such a

programme. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, the Labour leadership

has not made a statement on the issue. Even the local left-wing MP,

Chris Williamson, has only called for workers’ representation on the

board!

Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of

the Labour Party has not at this stage resulted in Labour being

transformed into a workers’ party. It remains two parties in one, as was

again demonstrated by the 75 Blairite MPs who defied the Labour whip to

vote in favour of Britain accepting all the neoliberal rules of the EU

single market. As long as Corbyn continues to maintain unity with the

pro-capitalist wing of Labour there will be a limit to how far he can

cut across the racism of the right.

Defeating this potential new

far-right force in formation, therefore, is not separate to the general

and immediate tasks of socialists. They include campaigning for a

fighting, democratic trade union movement that wages a serious struggle

for jobs, council homes, pay, benefits and decent public services. And

for the transformation of the Labour Party into a workers’ party with a

socialist programme.

English Uprising: Brexit and the

mainstreaming of the far-right

By Paul Stocker

Published by Melville House, 2017, £14.99