In

defence of socialist feminism

In

defence of socialist feminism

As the age of austerity

arising from the great crash of 2007-08 enters its second decade, a new

movement of women struggling against their oppression is taking shape.

But mistaken ideas on how oppression can be ended have resurfaced too.

The ideas of socialist feminism are ever more relevant, argues CHRISTINE

THOMAS.

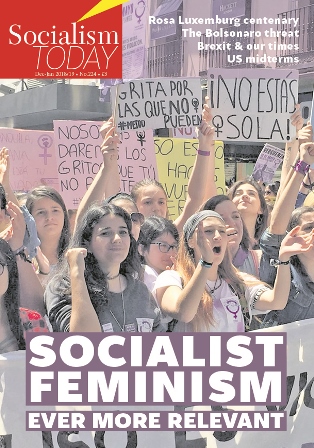

Feminism is back. All over

the globe women have been taking to the streets and speaking out about

gender oppression. Mass protests against violence against women have

erupted in response to horrific rapes and murders of women in India and

Argentina. On 14 November, more than 1.5 million students answered the

strike call of the

Sindicato de Estudiantes and

Libres y

Combativas, the socialist feminist platform of SE and

Izquierda Revolucionaria (CWI) against sexism in schools and in the

legal system of the Spanish state. In Ireland, Poland and Argentina

women have organised to defeat new and existing reactionary constraints

on their reproductive rights, challenging the stranglehold of the

Catholic church over social issues.

#MeToo has spread around the

world raising awareness of the scourge of sexual harassment, while the

elections of Donald Trump in the US and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil have

provoked massive movements against the sexism of both presidents and in

defence of hard-won rights for women against anticipated attacks. In

Scotland over 8,000 low-paid women working for Glasgow city council have

taken historic strike action to demand equal pay.

Although these are mainly

disparate movements, and not all countries have been affected in the

same way, it would probably not be an exaggeration to say that a third

feminist wave is on the move. This follows in the wake of the 19th

century first wave, and the second which mainly spanned the late 1960s

and 1970s. Each has been marked by its own characteristics, shaped by

prevailing economic and social conditions. However, it is also possible

to trace recurrent strands of thought and practice running through them

which socialist feminists need to address.

The 19th century women’s

rights movement emerged in the US from the struggle for the abolition of

slavery. If black people had the right to equality then so did women.

The leadership of the first wave internationally rested overwhelmingly

with middle-class women who principally emphasised their rights to legal

and political equality with men of their own class. This included the

right to vote but also equal access to the public spheres of higher

education, professional employment and politics which were considered

male preserves in contradistinction to the female domestic sphere. In

many countries, however, the late 19th century was also marked by a

growing confidence among industrial workers, explosive struggles by

sections of super-exploited workers, including many women, and the

consequent rise of new forms of trade union organisation, and the

development of socialist and Marxist organisations.

Increased access to higher

education and work outside the home spurred a questioning of wider

gender inequality by women involved in the second wave. The women’s

liberation movement, although never numerically large in an organised

form, succeeded in bringing questions concerning sexuality, gender

violence and women’s control of their own bodies into popular

consciousness. It developed against the backdrop of social

radicalisation and mass movements: international protests against the

Vietnam war, the powerful US civil rights movement, the fight for

national liberation in the colonial countries. Widespread strikes and

industrial struggles were also breaking out in many countries, at times

assuming a revolutionary potential.

In the US, the relationship

with the workers’ movement was quite weak. In Italy, on the other hand,

it emerged directly from the mass workers’ struggles and they were

closely linked. In other countries such as Britain, the workers’

movement also exercised an important influence on the feminist movement.

This was a time when the potential of the organised working class as a

viable agency for fundamental social change was evident. Yet those

struggles and strikes show how, even at times of mass struggle, the

relationship between the working class, revolutionary political

leadership and system change needs to be consciously drawn out. This was

highlighted by the events in France in 1968, when the working class was

prevented from overthrowing capitalism by the lack of leadership by the

powerful Communist Party.

The new wave

The current wave of protest

has developed in the context of the biggest post-war economic crisis and

the devastating consequences of a decade of austerity in many countries.

On the one side, the severity of the crisis has had a radicalising

effect on consciousness, resulting in a growing rejection of many of the

institutions and instruments which capitalism has relied upon

historically, such as the media, church and, most dramatically, the

traditional political parties. As the movements of women testify, this

changing consciousness is also giving rise to a challenging of the

sexist and divisive ideology capitalism has used to back up its economic

and social control.

At the same time, however,

consciousness is still being shaped by the legacy of the pre-crisis

period, when workers’ organisations were weakened by neoliberal attacks

and an acceptance of the dominant capitalist ideology following the

collapse of the Stalinist Soviet Union. Although there have been some

important workers’ struggles, particularly in Greece, Portugal and some

other European countries immediately after the crisis, collective

struggle has been at a historically low level in many of the more

developed capitalist countries. The inability or unwillingness of

leaders to fight back against neoliberalism, austerity and the effects

of globalisation have often led to a rejection of all political parties

and a scepticism about the ability of the working class to act as a

collective force for change.

The present global movement

of women combines elements of a new consciousness with vestiges of the

old. The fact that women, and other oppressed groups, are combining to

struggle against their shared oppression is a very positive development,

especially when contrasted with the previous two decades when the

emphasis was on individual rather than collective struggle.

‘Post-feminist’ ideas reached their peak in the 1990s and the turn of

the century. One of the main messages relayed through the media, popular

culture and politicians was that, by transforming their own attitudes,

shaking off victimhood and adopting sufficient determination, many of

the existing obstacles to gender equality could be overcome. As a

consequence, issues such as sexual harassment came to be increasingly

viewed as individual problems.

Today, collective struggles

involving a new generation of young women are once again raising

awareness of gender violence, sexism and inequality. Although #MeToo

developed initially as a mainly social media ‘movement’ dominated by

highly-paid women in the entertainment industry, it has found a huge

echo, lifting the lid on widespread sexual harassment and abuse by men

in positions of power and control. With the confirmation of Brett

Kavanaugh as a supreme court judge in the US the movement took to the

streets. Its impact beyond the realms of entertainment and politics

could clearly be seen when McDonald’s workers went on strike in ten US

cities in September to protest against workplace sexual harassment and

in the global walkout by thousands of Google workers.

Just like the previous waves,

the new movement is a contradictory one, with competing ideas and

strategies. These throw up theoretical and strategical challenges for

socialist feminists. During the first feminist wave, the major debate

for Marxist and socialist feminists revolved around how to relate to the

‘bourgeois’ women’s movement, as it became known, especially when

demands for the right to vote and legal equality with men were gaining

an echo among working-class women.

Many socialists, male and

female, felt it was not possible to campaign around issues of specific

concern to women related to their gender without this leading to the

division of male and female workers. There were fears that engaging with

the bourgeois women’s movement and its demand for legal changes within

the existing system would result in those ideas being absorbed by the

workers’ organisations, undermining the struggle for fundamental

economic and social change for the benefit of the whole working class.

These ideas were successfully resisted by women such as Alexandra

Kollontai in Russia and Sylvia Pankhurst in Britain.

Radical feminisms

The dangers of adaptation are

present in any movement in which different ideological trends emerge.

The main strands of thought competing in the second wave were bourgeois,

or liberal feminism, radical feminism and socialist feminism. It would

be more correct to speak of radical ‘feminisms’ as there were differing

ideas over the basis of male dominance. For some it was located in men’s

control over women’s sexuality. For others it was rooted in male

violence.

However, unlike liberal

feminists, for whom women’s inequality is caused by discrimination and

prejudice, radical feminism attempted to elaborate a social structure

theory of women’s oppression. This located gender inequality in a

patriarchal system in which men as a group dominate women as a group.

For most radical feminists, patriarchy was considered a social system

separate from capitalism and other systems of economic and social

inequality.

This theory of ‘the

patriarchy’ has been opposed by Marxist and socialist feminists. Basing

ourselves in particular on Friedrich Engels’ work, The Origin of the

Family Private Property and the State,* we have argued that

institutionalised male dominance is not universal, that societies have

existed in which egalitarian social relations have prevailed. Women’s

oppression is rooted in the emergence of societies based on class

divisions. It is so intrinsically intertwined with class society –

including today’s dominant form, capitalism – that it cannot be analysed

separately or ended without eliminating class society itself.

It is not always easy to stay

ideologically firm in the face of a new radicalised and enthusiastic

movement. Some socialist organisations, even some who defined themselves

as ‘Marxist’, allowed themselves to be swept away by the second wave,

adapting to the movement and accepting its ideas and strategy

uncritically. Even the use of terminology is very important as it

reflects underlying ideas. A loose use of the term patriarchy, for

example, adopted uncritically from the radical feminists, would have

given credence not just to the idea of two separate systems, but also to

the erroneous strategy flowing from this – a struggle against patriarchy

separate from the struggle against capitalism.

The second women’s movement

contributed to achieving important gains in many countries, including

the right to divorce, access to abortion and contraception, and

legislation outlawing unequal pay and discrimination. The more extreme

separatism of radical feminism, however, failed to provide a viable

strategy for ending women’s oppression, and its influence has since

waned.

In fact, another positive

characteristic of the current movements has been precisely the openness

of a new generation of women to involving men in their struggle, as well

as forming alliances with other oppressed groups. The idea that

different oppressions ‘intersect’ is in some ways a step forward from

the cruder strands of radical feminist ideas which tended to see women

as an undifferentiated social category, ignoring or downplaying

differences based on race, class, etc. ‘Intersectionality’, however,

tends to see class as just one form of oppression among many, without

understanding how all oppressions are rooted in the structure of class

society.

The effects of austerity

The economic crisis has led

to a certain undermining of the liberal feminist notion of securing

gender equality through gradual improvements within the capitalist

system. Even before the crisis, the much vaunted economic gains and

career advancements for women were mainly confined to the middle

classes, and the inequality gap between women widened. Nevertheless, the

idea that continual progress was possible gained a certain currency even

among many working-class women. The crisis and its effects have

destroyed many of those expectations, strangling at birth the hopes and

aspirations of a younger generation of women.

While there has been no

conscious master plan to turn back the clock and force women out of the

workforce and into the home, private sector job cuts, and particularly

the austerity axe wielded by governments on the public sector, have

destroyed many women’s jobs and increased the precariousness of those

which remain. At the same time, through the slashing of public services

such as nurseries and elder and respite care, working-class families in

particular are often left with no choice but to shoulder the extra

burden themselves. Most of this, and the harmful consequences it can

wreak on finances, health and personal relations, falls to women.

With women still

predominantly responsible for the care of children within the family,

especially at pre-school age, lack of affordable childcare is often the

main reason so many working-class women are still confined to low-paid,

female-dominated and part-time jobs, and a major factor contributing to

the gender pay and pension gap. Low pay means that working-class women

and families are unable to pay privately for childcare from their own

wages while the structural economic crisis means that state spending on

public childcare or financial subsidies to cover the cost of private

care is strongly resisted or cut back.

Inherent, therefore, in the

huge movements of women is not only the rejection of certain capitalist

institutions and sexist ideology but also the potential for the maturing

of a broader anti-capitalist and socialist outlook. However, this will

not be an automatic process. The inability of capitalism to deliver the

material interests of working-class women – jobs, pay, benefits,

pensions, etc – can be seen clearly during a crisis. The link between

class society and other aspects of gender oppression, such as violence,

sexual harassment and sexism, is less clear.

In the recent movements there

is often a tendency to consider these problems as deriving from the

behaviour or misogyny of individual men, or of a vague ‘culture’ which

encourages rape or sexism, without seeing how attitudes, behaviour and

culture are shaped by the capitalist society we live in and the ideology

carried over from previous class societies. The emphasis has therefore

been on raising awareness, educating men and changing attitudes and

behaviour without any of this being linked to broader economic and

structural change – much in the way that liberal feminists have argued

in past movements.

Class-based society

Socialist feminists believe

that all of these things are important. Violent and sexist behaviour

carried out by individual men should be challenged wherever it occurs.

We have always severely criticised those who have tried to ignore or

minimise such behaviour in the name of ‘unity’ between working-class

women and men. We have initiated broad campaigns which have raised

awareness about domestic violence (in Britain) and sexism in schools

(Sweden). Both of these campaigns had an effect in changing attitudes

and behaviour and, in the case of the Campaign Against Domestic

Violence, in securing changes in the law. But because of the nature of

capitalist society, legal reform, awareness raising, changing individual

men’s behaviour or changing ourselves can only go so far.

Violence against women,

sexual harassment, restrictions on women’s sexuality and bodily

autonomy, sexism and gender stereotyping are all rooted in unequal

relations of power and control. As part of the process of the formation

of the first class societies based on private property relations, women

became the property of individual men within the family unit – a social

institution which organised and controlled both production and

reproduction in the interests of the dominant economic class. Men within

the family, fathers or husbands, controlled women’s bodies with regards

to their sexuality and reproduction, often with the socially sanctioned

or encouraged use of violence. Women’s inferior status and social role

became enshrined in the legal system, backed by the church and other

institutions of class rule. Rape was considered a crime against the male

of the family whose property had been defiled.

Thousands of years later we

face a contradictory situation. Capitalism inherited the gender ideology

of previous societies as well as the institution of the family which it

then fashioned to suit its own economic interests. As economic and

social conditions have changed, however, the family and social attitudes

have undergone a sea-change in the more developed capitalist countries,

particularly over the past few decades. Rigid gender norms and the idea

of the traditional family unit have been undermined in many countries by

the influx of women into the workforce, the increase in single-parent

households, recognition of same-sex marriage and the growing acceptance

of transgender people. The victory of the movement for legal abortion in

Ireland, and the near victory in Argentina, has shown how it is possible

to defeat the reactionary ideas still promoted by the Catholic church

regarding women’s reproductive rights.

Nonetheless, backward

attitudes and behaviour can continue to flourish long after the initial

material basis for those ideas has disappeared. The capitalist system,

for example, no longer directly promotes violence against women in most

advanced capitalist countries. On the contrary, important laws have been

passed around this issue and it is generally viewed as a social problem

which should not be tolerated.

However, capitalism is based

on unequal economic and social relations in the workplace, the family

and in wider society. The segregation of women in low paying sectors of

the economy and the transfer of the burden of public services to the

family make it more difficult for women to leave violent relationships.

Moreover, they sustain the inequality and inferior status from which

gender violence derives.

Norms of gender roles,

behaviour, dress and imagery are perpetuated and shaped from cradle to

grave, reinforced by capitalist institutions like the media, the

education system, the judiciary, etc, as well as the beauty, leisure and

fashion industries. Capitalism is a system in which commodities are sold

on the market to make a profit. That commodification is extended to the

bodies of women, both directly through the sex ‘industry’ and indirectly

through images and text. The internet and social media have merely

expanded the instruments through which sexist gender norms can be

diffused. Bringing an end to rape, sexual harassment, domestic violence,

sexism and gender discrimination cannot, therefore, be achieved without

fundamental structural change – eradicating the capitalist system and

the network of unequal economic and power relations on which it is

based.

The role of the working class

One of the challenges for

socialist feminists is to explain the centrality of the working class in

the process of changing society – because of its role in the capitalist

production process and its potential collective consciousness – and to

orient the new generation of female fighters towards the working-class

movement. One of the strengths of the Campaign Against Domestic

Violence, which was launched in the early 1990s and rapidly became a

broad-based campaign, was its ability to orient towards the working

class.

For the first time, it

established domestic violence as a workplace and trade union issue. It

explained how the violence experienced by women in the home also impacts

on their working life and the role that unions could play in securing

economic and social change to enable women to leave violent

relationships and lead independent lives. This was achieved despite the

fact that the link between domestic violence and the workplace was not

immediately clear and despite the opposition of radical feminists who

were opposed to any link with ‘male-dominated’ trade unions.

At a time of low level

workplace and industrial struggle, explaining the central role of the

working class is not necessarily a straightforward issue. A positive

aspect of the current international movement, however, has been its

adoption of the strike as a weapon of struggle (on 8 March,

International Women’s Day, for instance) and the turning to male workers

for solidarity. The two-day strike of Glasgow council workers was

extremely significant. Thousands of women workers stopped work to battle

for equal pay, while male refuse workers and others took illegal

secondary action and refused to cross picket lines to support them. The

McDonald’s and Google strikes against sexual harassment and unequal pay

were also vivid examples of the potential of forging unity between

female and male workers around an aspect of gender oppression, in this

case in predominantly unorganised sections of the working class.

Challenging right-wing populism

The other challenge is the

need to create and build the political instruments which system change

requires. On the one hand, capitalism’s economic and political crisis

has fuelled a rejection of capitalist institutions and ideology. On the

other, the bankruptcy of the traditional parties of the working class

and the absence of viable anti-capitalist political alternatives have

resulted in the anti-establishment mood being electorally channelled

towards right-wing populism in a number of countries.

Trump, Bolsonaro, and Matteo

Salvini and the Lega in Italy, have openly expressed sexist opinions or

behaviour and espoused socially reactionary ideas. Even though these

ideas are not necessarily supported by the majority of the population,

or even a majority of those who voted for them, they pose a real danger

to the social rights of women and other oppressed groups. Trump, in

particular, has been able to create a social base among a layer of white

men who feel alienated and undermined by economic crisis and social

change, and are receptive to prejudice and backward ideas about women

and other social groups.

In the US, the ground is

being prepared for a further undermining of abortion rights and attacks

on transgender rights. In Poland, an offensive has been launched against

women’s already very limited abortion rights. In Italy, the government

is discussing a law in the name of ‘parental equality’ which would

actually make divorce more difficult for women with children and

increase domestic violence. The mass demonstrations on Trump’s

inauguration day, and the outpouring of women onto the streets in the #NotHim

protests against Bolsonaro before and after his election, give an

indication of the scale of resistance that future attacks could unleash.

In Italy, Non Una di Meno,

which was inspired by the movement in Argentina, has become one of the

most organised and influential women’s groups internationally, capable

of mobilising tens of thousands of women and men. Victories can be won,

as we have seen in several countries, but those gains will always be

vulnerable to further attacks, as the renewed offensive in Poland has

demonstrated, unless a political alternative is created to challenge the

root causes of the problems women face.

With all their

contradictions, the new women’s movements represent the first stirrings

of a potentially broader working-class and anti-capitalist struggle. A

new generation of young women fighters are being radicalised and

mobilised, and could be won to the fight for socialist change. There

will be attempts to orient these movements towards existing capitalist

political parties – towards the Democrats in the US, for example – or to

remain completely independent from all political parties, regardless of

their orientation, as with Non Una di Meno. The challenge for socialist

feminists is to participate in the movements, engage with the ideas and

strategies which emerge, while maintaining ideological clarity. To

explain how the struggle to end gender oppression in all its forms is

only possible in the framework of a broader struggle by the working

class against the capitalist system itself.

* Although some of the

facts on which Engels based his ideas have been refuted by subsequent

scientific and anthropological developments, the general theory of the

interconnectedness of class and gender oppression retains all its

validity (see:

Engels and Women’s Liberation, Socialism Today 181, September 2014).