The analysis made in the 2009

article has retained its validity in the aftermath of Thatcher’s death.

We wrote then: "Even before she has departed this world, a ferocious

controversy rages over her heritage, with mass indignation at the idea

of state recognition for her and her role". (Socialism Today No.128, May

2009)

And so her funeral proved to

be. It was carried out at the cost of an estimated £10 million. The

Socialist Party demanded that Thatcher should be treated in death as she

treated others in her lifetime. The funeral should have been

‘privatised’ with Mark Thatcher – with an estimated fortune of £80

million – called upon to make a contribution, along with the sharks in

the City of London and big business. They benefited most from her

policies.

But "the best-laid schemes o’

mice an’ men/Gang aft agley" (go often awry), wrote Robbie Burns. The

careful calculations of the entire establishment that Thatcher’s funeral

would be an enormous political bonus for them have blown up in their

faces. All the festering discontent, inherited from the Thatcher period

and added to by the Blair and Brown governments, has surfaced. The sheer

class hatred from the victims of Thatcherism, both past and present, has

been expressed in their bitter opposition: "You didn’t care when you

lied. We don’t care that you died", proclaimed a banner held by

Liverpool fans at a football match, protesting against the Hillsborough

slander campaign and cover up by Thatcher and her government.

Thatcher sycophant Andrew

Marr, on his return to television, added his dose of poison against the

people of Liverpool with the completely false assertion that, in 1979,

the city council considered dropping the unburied dead into the sea

during the action of low-paid public-sector workers!

A ferocious condemnation of

‘Operation True Blue’ – the secret preparations for the funeral made by

Tory and Labour frontbenchers with the support of the Liberal Democrats

– was the result. Those who suffered directly at her hands were reminded

of the brutal methods which she and her government employed,

particularly against the miners, Liverpool city council, the print

workers and many others. Young people, who were not even born when she

was in power, nevertheless began to understand that she and her cohorts

laid the basis for the catastrophic position which they face today.

Thatcher quite consciously

destroyed manufacturing industry, as we explain here, as a precondition

for weakening the power of the working class and its organisations, the

trade unions. The consequence was an army of poor, which persists and

has grown, and a slashing of wages, with the replacement of relatively

highly paid manufacturing jobs with low-paid ones.

The beginning of the

dismantling of the welfare state was also a result of her policies,

which her heir, David Cameron, is carrying through today.

Semi-dictatorial methods, such as severely curtailing the right to

strike, were put in place. John Stalker, ex-deputy chief constable of

Greater Manchester, wrote in the Daily Mirror that she "took us to the

brink of being a police state" during the miners’ strike.

Thatcher also backed to the

hilt every bloodthirsty dirty dictator on the planet. Counted among her

‘friends’ were the Chilean dictator General Pinochet, the Pakistani

dictator General Musharraf and many others. Moreover, an article in the

Observer on 14 April showed that, even when she was out of office,

"Thatcher 'gave her approval' to son Mark's 2004 coup attempt in

Equatorial Guinea". That was a plot against a dictatorship, with the

prospect of massive financial gain as its aim. She also later urged

Simon Mann – who alleges that Mark Thatcher was closely involved in the

plot – to join a conspiracy to overthrow the democratically elected

leader of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez.

Is there any doubt that

Thatcher would have given support to similar methods – the destruction

of democratic rights – against the British working class and people if

the situation required it, ie if capitalism was endangered? She

indicated this in her anti-union laws. Without the right to strike, free

of all state interference, there cannot be real democracy. The

maintenance of her anti-union laws by Blair and retained by Cameron is a

big impediment for the working class today to fight effectively the

continuation of her policies by the Con-Dem coalition.

At one stage, Thatcher and

her theoreticians criticised ‘elected dictatorships’, usually radical

regimes which threatened to go beyond the bounds of capitalism, the

system she defended. But her government was, in the true sense of the

term, an elected dictatorship. Never once did the governments she

presided over present their full programme in elections. But, once in

power, they proceeded to implement vicious, class-based measures which

enhanced the position of the minority, the greedy rich, at the expense

of the overwhelming majority, the working class, the poor and the middle

classes.

The attempt of the capitalist

media to burnish her image as a ‘wonder woman’, who ‘transformed Britain

and the world’ is a great exercise in historical amnesia. The claim to

have established a ‘property-owning democracy’ lies in ruins. Owning a

house now is completely out of the reach of the young generation.

Private landlords own one third of former council homes!

She also carried through an

economic revolution in Britain, claim her acolytes. This is completely

false, as even capitalist commentators like Will Hutton have shown.

Average growth rates when she was in power were lower than in the

previous 20 years. Moreover, the ‘big bang’ in the City of London led to

the orgy of unrestrained financialisation of capitalism, as we warned

would happen at the time. This helped to create the conditions for the

2008 economic crash, which the governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn

King, described as the "worst ever".

Thatcher is dead, but

Thatcherism lives on in the three main political parties in Britain. She

created ‘mini-Thatchers’ at local as well as national level who are busy

today savaging services and jobs in the public sector. How hypocritical

that a £15 million Margaret Thatcher library and museum is to be opened

after her death, while the little Thatchers are busy closing libraries

up and down the country as part of the cuts programme.

When asked what her greatest

achievements were, Thatcher replied: "New Labour, Tony Blair". We must

draw all the necessary conclusions from this in fighting energetically

for a new mass party of the working class.

One of the conclusions we

drew in 2009 was that: "A Cameron government would be a re-run for the

working class of the experience of Thatcher herself, only probably much

worse because the economic situation is dramatically worse than during

her reign. It would provoke a massive social confrontation, probably

even forcing the conservative officialdom of the TUC to move into

action. A one-day general strike could come quickly onto the agenda".

This has been borne out, with

the TUC forced into unprecedented mass action with the demonstration on

26 March 2011 and the subsequent strikes. A 24-hour general strike has

not yet been implemented. But the idea of a general strike is rooted in

the situation. The death of Thatcher provides the opportunity for us to

build a movement that will eradicate the conditions which bred

Thatcherite capitalism, and raise the alternative of a democratic,

socialist planned economy.

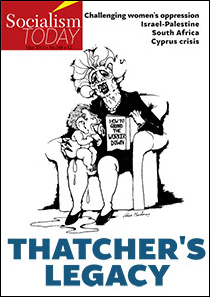

Thatcher’s

bitter legacy

Thatcher’s

bitter legacy

Margaret Thatcher was not cut

from the same cloth as those representatives of British capitalism who

preceded her at the head of the Tory party. Post-1945 Tory prime

ministers, in the main, such as Harold Macmillan, presided over a

‘post-war consensus’, which prescribed that the government and the

ruling class would seek to avoid a head-on confrontation with the

organised labour movement. Following in the so-called ‘Whig tradition’,

Tory grandees developed the special art of British statecraft, by

bending with the class and social winds. This served them well during

the post-1945 boom in accommodating to the tops of the labour movement

in particular in ‘sharing out’ a growing ‘cake’. But the ‘slow

inglorious decay’ of Britain was masked during the boom. When this ran

out of steam it inevitably culminated in a collision between the

classes. This took shape in the 1960s but intensified in the tumultuous

1970s and 1980s.

The Heath government that

came to power in 1970, following the dismal failure of the Labour

government of Harold Wilson between 1964 and 1970, set out to correct

the decline of British capitalism, naturally at the expense of the

working class. Edward Heath, although not himself a grandee – he was a

‘grammar school boy’ – was in the same political tradition as his Tory

forebears. He nevertheless threatened the labour movement with the idea

of provoking a ‘general strike’ which the government would defeat.

However, when his government confronted the miners in 1972 and 1974, it

lost both times. The latter strike led to the three-day week and the

defeat of the Heath government in the February 1974 election.

These events, particularly

the unprecedented event, for Britain, of an industrial dispute provoking

a general election and the defeat of the Tories, exercised a profound

effect on the strategists of British capitalism. Heath gambled on an

election whose theme was ‘Who rules, us or the miners?’ and he lost. The

ruling class began to prepare for the future when it could take revenge

on the labour movement. Heath was unceremoniously thrown overboard and

replaced by Thatcher in early 1975. Formerly a minor figure in Heath’s

government, as education minister she had already earned an anti-working

class mantle as ‘Thatcher, milk snatcher’ for removing free school milk

for primary school children. But her ascent to the Tory leadership was

no accident. Friedrich Engels, alongside Karl Marx, the originators of

the ideas of scientific socialism, commented that each era calls for

personalities required by objective circumstances. But if they do not

exist in a rounded-out form, it ‘invents’ them. Thatcher, without any of

the scruples or hesitation of the aristocratic Tory grandees, was the

brutal face of British capitalism required by the situation. She not

only polarised society but the Tory party itself.

The divisions between the

Thatcherite ‘dries’ or ‘hards’ and the Heathite ‘wets’ were found not in

any personality clashes but in the methods chosen to confront the labour

movement following the latter’s triumph over the Heath government. The

wets correctly feared that Thatcher and her government would lead to a

class confrontation which would question the very basis of capitalism.

They remained unreconciled to Thatcher for almost all of her reign but

largely accommodated themselves to her government when it appeared to

score successes.

The winter of discontent

Buttressed by ill-digested

ideas from the ultra-right Austrian economist, Friedrich Hayek, and the

messianic monetarism of her ‘mad monk’, Sir Keith Joseph, Thatcher

capitalised on the retreats and ineptitude of James Callaghan’s Labour

government. This government was more set on confronting the legitimate

demands of trade unionists than the dire economic situation which was

developing, culminating in the so-called ‘winter of discontent’. The

strikes of the most lowly-paid workers were vilified by the capitalist

press, the Tories and even by the Labour government as the ‘dirty jobs’

strike.

Militant (forerunner of the

Socialist Party) warned in October 1978: "Sooner or later… the

strategists of capital will conclude that the Labour government has

served its purpose as far as they are concerned. In any case, if the

government continues its present policies into next year, especially if

it takes on more and more sections of workers fighting for decent living

standards, it will virtually ensure a defeat for Labour". These

prophetic words were, unfortunately, borne out in the May 1979 general

election.

Militant also warned that

Thatcher "would eventually be forced to launch an offensive against the

working class and its organisations. Ridley indicates this". This refers

to Tory shadow cabinet minister Nicholas Ridley, who had prepared a

blueprint for confronting the unions. He had written that "in the first

or second year after the Tories’ election, there might be a major

challenge from a trade union, either over a wage claim or redundancies".

Ridley thought that this would come in the mines and therefore proposed:

"A: build-up of maximum coal stocks, particularly at power stations; B:

make contingency plans to import coal; C: encourage the recruitment of

non-union lorry drivers by haulage companies to help move coal where

necessary; D: introduce dual coal/oil firing in all power stations as

quickly as possible". Right-wing Tory MP, Ronald Bell, again indicating

the future role of the Tories, stated: "Strike-breaking must become the

most honourable profession of all".

The winter of discontent

generated all the class spite which was to become the hallmark of the

Thatcher years. At Reading hospital, for instance, patients who turned

up for treatment were asked whether they were trade unionists. Those who

answered yes were refused treatment by a consultant surgeon. We pointed

out in Militant at the time: "The demand for a living wage is seen as

treachery by the capitalists". However, the Callaghan government had run

out of steam and was incapable of imposing the will of the capitalists

on an almost insurgent labour movement. Noises began to be made about

splitting the Labour Party – which, at that stage, was still a workers’

party at the bottom, although with an increasingly pro-capitalist

leadership – and the formation of a national government. A left-wing

Labour MP of the time, the late Stan Thorne, revealed that some

right-wing Labour MPs had been involved in secret talks with the

Liberals and Tories on the issue of splitting Labour and forming a new

national government, as a previous Labour leader, Ramsay Macdonald, had

done in 1931.

This proposal has resurfaced

in the capitalist press in relation to the Brown government. So dire is

the present situation that there is despair that any government – let

alone a David Cameron-led Tory cabinet – could ignite a social explosion

if it tried to solve the crisis with draconian pro-capitalist measures.

Therefore, why not a ‘government of all the talents’? This is probably a

non-runner before an election but if there is a hung parliament, with no

party in overall control, then it could resurface. A coalition

government is, however, as the 1930s showed, just a Tory government in

disguise.

The plans in the 1970s came

to nothing because the government that the capitalists expected would

follow the next general election would be firmly under their control.

Moreover, it would be determined, as we pointed out in Militant, to

confront the working class: "A Thatcher government will be even worse

than the hated Heath government which was kicked out by the trade unions

in the economic chaos of the three-day week… The Tories want the state

to interfere with the unions – outlawing flying pickets, breaking the

unity of closed shops and imposing rules on union elections as a

condition of unions being ‘certified’ by the government, similar to the

‘registration’ under the notorious Industrial Relations Act".

Preparing to attack the working class

Militant, in other words,

outlined in advance exactly the programme on which Thatcher was elected

in 1979 and explained how she and her cabinet were likely to act once in

power. However, prior to the election, while ruthlessly preparing behind

the scenes, Thatcher took pains to disguise her real intentions.

Unbelievable as it sounds today, and in view of the havoc over which her

government presided, Thatcher quoted St Francis of Assisi on the need to

end discord as she entered No.10 Downing Street! In her very first

budget, however, paltry tax concessions were given to average wage

earners, which would be wiped out by inflation in a few months, while

value added tax was increased to 15% and the Tories gave notice of

further savage attacks on the living standards of working people.

The right wing of the Labour

Party had prepared the basis for Thatcher by both failing to tackle the

problems of the working class but, at the same time, seeking to aim

blows against the left and particularly against Militant. Two Labour

prime ministers – Wilson, who had resigned in 1976, and Callaghan, who

took over from him – had scathingly attacked Militant in a dress

rehearsal for what was unleashed by the later Labour leader, Neil

Kinnock, and his allies in the 1980s. Callaghan stated on TV: "We

[Labour Party leaders] neglected education. We have allowed it all to

fall into the hands of the Militant group. They do more education than

anybody else".

The Labour right wing,

however, wished to ‘educate’ young people and the working class by

teaching them to accept cuts in living standards as a fact of life. In

fact, the right wing began an almost permanent war against the left,

with their main figures, such as David Owen and Roy Jenkins, threatening

a split, which subsequently took place with the formation of the Social

Democratic Party (SDP). This eventually collapsed into a merger with the

Liberals, becoming the Liberal Democrats, but they were the praetorian

guard of the capitalists’ attempt to purge the left from the Labour

Party. In January 1980, The Times, then the house-journal of British

capitalism, under the headline, ‘Time for a Purge’, called for action to

be taken against Militant.

At the same time, the

predicted offensive against the working class, both by the government

and the employers, together with the rise in unemployment, provoked

mighty working-class resistance to the Thatcher government. This was

demonstrated by the 140,000-strong TUC demonstration through London in

March 1980. The Times, at this stage, was speaking about the

"irreversible decline" of British capitalism.

The mood began to grow for

the TUC to call a one-day general strike, which was eventually watered

down into a ‘day of action’. Nevertheless, 14 May 1980 was still a

massive demonstration of working-class opposition to the Tory

government. This was followed in November 1980 with an historic Labour

Party demonstration of 150,000 against unemployment in Liverpool.

Massive demonstrations followed in Glasgow, Cardiff, Birmingham and

London. For the first time in generations, the Labour Party had actually

taken the initiative in mobilising working-class people in action.

Such was the relationship of

forces that the Thatcher government was compelled to step back

temporarily from its plans for a head-on confrontation with the labour

movement. This was shown in the mining industry in early 1981. The

threat to begin a programme of mass pit closures was met with the threat

of immediate strike action in South Wales. This panicked the government.

Thatcher, for the first time since she had come to power, was forced

into a humiliating retreat. But Militant warned: "The miners showed what

could be done by bold and determined action, but if the Tories were

allowed to do it they will come back later with further attacks on

workers’ rights and living standards". This was what had happened in

1925, when the capitalists, facing resistance from the miners, bided

their time to prepare for the 1926 general strike. Unfortunately, the

tops of the trade unions complacently accepted the situation in 1981

without any serious preparation for future battles. The miners were to

pay a very heavy price later, as Thatcher and her boot boy, Ridley,

built up coal stocks, beefed up the police, and prepared new laws in

order to try and smash the miners.

Catastrophic de-industrialisation

Britain was politically

convulsed at this time with the very existence of the government in

peril. Riots erupted in Bristol, Liverpool, London and other inner-city

areas, class polarisation developed on an unprecedented scale and, as a

by-product of this, the ideas of Marxism, signified by the dramatic

growth of Militant, became more popular. The Thatcher government,

however, relentlessly pursued its mad policies of monetarism – squeezing

inflation out of the system and cutting down the money supply – which

resulted in the wholesale closure of factories. This enormously

aggravated the economic crisis developing at this time in Britain and

internationally.

It was this period that

ushered in the catastrophic economic devastation of British industry,

which was in decline but was furthered by Thatcher. So terrified was she

and British capitalism of the industrial working class, signified by the

defeat of Heath and Thatcher’s step back in 1981, that she was prepared

to contemplate and even half-welcome the de-industrialisation of

Britain. Manufacturing industry collapsed on an unprecedented scale.

Manufacturing output dropped 30% from its 1978 level by 1983 and

unemployment reached 3.6 million. This reduced British capitalism to a

minor player in manufacturing production and competition on the world

markets.

We consistently warned at the

time and since that the substitution of a casino economy of the

‘candyfloss’ industries of finance, banking, etc, in place of

production, of industries producing real value, would ultimately result

in a catastrophe for British capitalism and the British people.

This appeared to be falsified

by a combination of factors which saved Thatcher’s skin during her first

government. The most overwhelming reason was the cowardice of the

right-wing leadership of the trade unions, who refused to take decisive

action, for instance, when the most brutal anti-working class,

anti-trade union legislation in the advanced industrial world was

introduced. Weakness invites aggression. Prevarication, hesitation and

outright cowardice were the hallmarks of the right wing of the trade

unions both then and today. This emboldened the Tories. Thatcher was

also saved by the Falklands war. Napoleon wished for ‘lucky generals’.

Thatcher herself came very close to military disaster in this war but

her luck held out and she managed to defeat the even more unpopular and

decrepit Argentine dictatorship of General Galtieri in 1982. This

allowed her the full backing of the patriotic press of Britain, with the

Sun in the vanguard, conjuring up Britain’s past imperial ‘glory’.

The miners, Liverpool, and the poll tax

This Falklands factor, in

turn, laid the basis for Thatcher to go into another general election in

1983. Her hand was strengthened by the pusillanimity of Labour, this

time led by the hapless ‘left’ Michael Foot, who presided over the

expulsion of the five members of the Militant newspaper editorial board.

Also, the recuperation economically from the crisis of 1979-81 furthered

the Tories’ cause with the promise of ‘economic glory’ to follow what

had been achieved in the South Atlantic. This laid the basis for

Thatcher to recommence her war against the miners.

The outcome of the 1984-85

strike was not at all predetermined, as some have argued. In fact,

Thatcher’s government was about to capitulate just a short time before

its end. But a decisive and pernicious role in the defeat of the miners

was played by the right wing within the trade unions and the equal, if

not greater, treachery of Kinnock, the then Labour leader. A similarly

treacherous and cowardly role was played by Kinnock and other Labour

leaders in the Liverpool struggle between 1983 and 1987. A socialist

Labour council had begun to transform the lives of the people of the

city and, moreover, had achieved something that neither Galtieri nor

Kinnock had managed, that is, to defeat Thatcher in 1984. This excited

the most vicious hostility from Kinnock and his entourage.

At the same time, Thatcher

undoubtedly found some political succour in the economic changes being

wrought in Britain and worldwide. The neo-liberal economy, characterised

by the development of new technology, was beginning to take shape.

Thatcher, using the limitations of the past so-called ‘mixed economy’

under Tory and Labour governments, almost stumbled on the idea of

privatisation, of which she was a ‘late convert’, to begin her

‘revolution’, in effect a counter-revolution.

Ideologically, the labour

movement, under right-wing domination, was unprepared for Thatcher’s

offensive. The halfway house of the mixed economy, with a

bureaucratically-run state-capitalist sector in the hands of the

government and its appointees, and the majority of the economy in the

hands of private capitalists, had reached a dead end. Thatcher and the

right-wing ideologues that bolstered her, such as Milton Friedman,

seemed to offer a new, exciting departure from the discredited

quasi-managed Keynesian model. The sale of council housing, combined

with selling off profitable sections of state industry (what former Tory

leader, Harold Macmillan, termed the ‘family silver’) followed. This

received hosannas alongside the soaring of the stock exchange, not just

from British but world capitalism, which hailed Thatcher’s ‘experiment’

as the prototype for a new capitalist Eldorado. And it certainly was for

a few, as profits and the capitalists’ incomes soared, and the City of

London benefited in a new orgy of financialisation.

We warned that this would end

in tears, not just for the working class but for capitalism itself.

Thatcher was answered ideologically by us but crushingly in life by the

development of the current economic crisis. According to Thatcher, the

combination of Britain’s North Sea oil receipts and the ‘expertise’ of

the service sector, led by the banks and finance houses of the City, was

the answer to the ‘discredited’ theory of a manufacturing base. But it

is impossible to open any newspaper today without seeing a devastating

rebuttal, either indirectly or directly, of Thatcher’s ideology, and

with it that of the overwhelming majority of the capitalists in Britain.

Every single platform of Thatcherism has been reduced to dust. The

famous ‘property-owning democracy’ lies in ruins as homelessness,

repossessions and negative equity become the norm for millions. House

building is at its lowest level since 1924 and five million people in

Britain would now like to live in decent ‘social housing’.

Thatcher was defeated, not on

the issue of Europe, as countless commentators have claimed, but on the

poll tax. And it remains an incontestable historical fact that it was

the Marxists around Militant who played the decisive role in this

battle. On this issue, Thatcher herself had no doubt: "The eventual

abandonment of the charge represented one of the greatest victories for

these people [the organisers of the anti-poll tax demonstrations on 31

March 1990] ever conceded by a Conservative government". (The Downing

Street Years, p661) Absolutely decisive in this battle was the campaign

for non-payment, initiated by Militant comrades in Scotland and taken up

on a mass scale one year later in the rest of Britain. Eighteen million

non-payers of the poll tax finished it off and in the process reduced

the ‘iron lady’ to iron filings.

The defeat of laissez-faire capitalism

Thatcher represented

primitive, brutal, class warfare against the rights and conditions of

the working class. The lesson of Thatcherism is that capitalism under

whatever guise is incapable of ultimately delivering the goods for the

working class, either in Britain or on a world scale. She helped to

enshrine for an era the ideas of neo-liberalism. Ideologically, they

were countered by the very small force of genuine Marxism with the

majority of intellectuals and leaders of the labour and trade union

movement adhering to the ‘Washington consensus’, that is, Thatcherism on

a world scale. Militant (to become the Socialist Party) and the

Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI) stood out. But the reality

is that the pro-capitalist parties in Britain have not completely

abandoned the economic heritage of Thatcher. Yes, the most ‘dangerous’

aspects for them have been relegated to history – unregulated,

unrestrained financialisation of capitalism – but the same intentions

are still there. Their mantra is that the working class must pay for

this crisis. Our answer is at one with those workers and youth

demonstrating in Italy, in Germany and elsewhere earlier this year, who

marched under the slogan: ‘This is not our crisis!’

Larry Summers, the main

economic adviser to president Barack Obama, desperately tries to

separate this crisis from capitalism itself: "There are those who just

as in the 1930s tried to learn the lesson that capitalism did not work

and needed to be replaced with an entirely different model. I don’t

think that’s right". The problem for Summers is that a growing number do

not agree with him. For instance, an online poll, in March, for a German

TV talk show answered the question: ‘Which economic system is better for

you?’, with the result, capitalism 46%, socialism 54%.

No poll can fully portray

what the mass consciousness is. But one thing is clear; ‘laissez-faire’

capitalism has been defeated. The state has been forced to step in to

rescue the system. The capitalists do not like this because this raises

the idea of not only rescuing the banks but also the majority of other

industries which are on their backs. Not just the Tories oppose this but

so do the Liberal Democrats, with the allegedly ‘radical’ Vince Cable

coming out against long-term state intervention (‘dirigisme’), and

voicing hostility to further state rescues for firms like Visteon by the

government. The consequence of this hands-off policy will be an

inexorable rise in unemployment and growing discontent, which is laying

the basis for a massive radical movement in Britain and worldwide.

Thatcher has been pictured as

a towering presence during her lifetime. Yet even before she has

departed this world, a ferocious controversy rages over her heritage,

with mass indignation at the idea of state recognition for her and her

role. She was an important, but is now a diminishing, factor in British

politics. There is nothing for the most politically developed workers to

learn from Thatcher, from the era that she represented, other than, no

matter who represents this system they will attempt to pin the blame and

the burdens of capitalism on the backs of the working class. Whether it

is the face of Thatcher or the seemingly more ‘acceptable’ visage of

Cameron, implacable opposition to them and their system, combined with

intransigent criticism of those at the summits of the labour movement –

who are not prepared to oppose them, root and branch, as the miners,

Liverpool and the poll tax protesters did – must be the cardinal

principles of a revitalised labour movement.