Whatever the exact course events might take in the weeks and months ahead, the possibility of the development of a new, mass vehicle of independent working-class political representation is now part of the consciousness of all classes in Britain, as the multi-faceted crises of capitalism unfold.

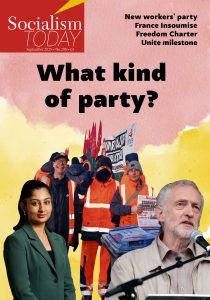

This is the indelible result of the appeal made by Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana on July 24 to join in the founding of “a new kind of political party”, based on “a mass redistribution of wealth and power” against the “rigged system”.

There is no one blueprint readily available for what next. For how to get from the nearly three-quarters-of-a-million sign-ups who have answered the ‘Your Party’ call, to the actual formation of the new, mass, democratic socialist party the working class needs, with its programme, structures or even its name agreed. And nor could there be. But the challenge has been laid down to “the interests of corporations and billionaires” that Corbyn and Sultana take aim at in their declaration, and the fight for such a party of the working class to be established is on.

Corbynism 1.0

The same threat to the capitalist ruling class was true, of course, of Corbyn’s insurgent campaign of ten years ago which, in September 2015, saw him unexpectedly elected as the leader of the Labour Party. His victory then also threatened to overturn the historic gain that had been made – for the capitalists that is – by Tony Blair’s transmutation of the Labour Party into ‘New Labour’ in the 1990s. With its commitment to the ‘free market’, to anti-union laws, austerity and war, and the gutting of the trade unions’ role within the party, for over 20 years the working class had been effectively disenfranchised, to the material gain of the capitalists.

The ruling classes’ interests were threatened by the hopes unleashed, but the battle was not resolved. Jeremy Corbyn’s victory then was a bridgehead for the working class against the capitalists, including their representatives within the Labour Party. But only a bridgehead, which should have been the first step to reconstituting Labour as a mass workers’ party. Instead, in less than five years, the Blairites were firmly back in control.

But that outcome was not preordained. And learning from the lessons of that experience will be a vital part of ensuring that the new opportunities for working class political representation and socialist policies that the moves to a new party has created can be successfully realised this time.

In many of the ‘what next?’ discussion meetings and forums that have taken place after the July 24 Your Party call, however, where the question of how the new party will be organised has been a prominent concern, some have dismissed the idea that any lessons can be drawn from the historical experience of the Labour Party. But this really is ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’.

In her article on page eleven Christine Thomas looks at some of the positive features of the founding structures of the early Labour Party, which involved pre-existing separate socialist parties coalescing with trade unions, community-based organisations and social movements to create a unity in action, including electorally. This ‘federal’ structure was able to harness the enthusiastic work of activists from disparate organisations, without which the new party would not have been sustained. With membership reaching one million by 1907 it was local trades councils, the branches of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) or miners’ union lodges (branches) – even before the union nationally had affiliated – that were the backbone of the local structures of the party in the initial years.

As the article explains, this didn’t resolve how to resist the pressure of the ruling class on the new mass party not to adopt the full socialist programme necessary to transform society. But that was not the result of the party’s federal structure, which at least enabled workers’ counter-pressure to be organised and the debate to continue.

What could have been done

Negative lessons, from Labour’s recent history, are also important too. Under Jeremy Corbyn Labour experienced a mass surge in membership, with the official year-end figures reported to the Electoral Commission rising from 193,754 in December 2014 to a peak of 564,433 in 2017. The Fire Brigades Union, having disaffiliated in 2004, reaffiliated in November 2015. But the qualitative changes to the character of the Labour Party in its transformation into New Labour – that had blocked off the avenues for genuine democratic participation – still remained.

The militant RMT transport workers’ union also began a discussion about re-affiliation, having been expelled from Blair’s New Labour for its support of Scottish socialist candidates in 2004. In these debates the Socialist Party discussed with our allies in the union on the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) steering committee what would be necessary to really uproot the political and organisational legacy of Blairism and, building on the bridgehead of Corbyn’s leadership, realise the goal of workers’ socialist political representation.

First, most clearly, was mandatory re-selection of MPs – with unions having the right to directly nominate candidates onto parliamentary shortlists. Then there was the situation in local government, with right-wing Labour Mayors and councillors discrediting Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-austerity message by implementing local cuts and privatisation agendas. The call here was for a restored ‘district Labour Party’ structure – with union branch delegates sitting alongside ward party delegates with the power to democratically decide local election manifestos and elect council Labour Group officers. Similarly the demand to restore representative democracy in the administration of local parties, with a full role for affiliated union branches in Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs).

Another demand was the abolition of the National Policy Forum, where unions held just 16% of the votes – the RMT would have had less votes than the House of Lords Labour Peers Group if it had affiliated! – and the restoration of policy-making power to the party conference. And an end of the MPs’ veto over who could be a leadership candidate – by introducing a qualifying threshold based on CLP and trade union nominations only.

And the call for an explicit commitment to socialism, which remains part of the objectives of the RMT in its rulebook clause “to work for the supersession of the capitalist system by a socialistic order of society”. A new Clause Four was needed – replacing that introduced by Tony Blair in 1995 praising “the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition” with a commitment to a democratic socialist society based on the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange.

And finally, reinstating socialists who had been expelled or otherwise excluded, with their right to be organised ensured – to allow the affiliation of socialist parties and anti-austerity, anti-racist, socialist feminist and Green campaigns and organisations in a modern version of the early federal structure of the Labour Party.

But none of these featured in the affiliation ‘offer’ made to the RMT and after a full branch consultation, not convinced that their working-class voice would be represented, a special general meeting voted to preserve the union’s own, independent political position. There are lessons here for the new party.

Seizing moments

In 2017 Jeremy Corbyn had gone over the heads of the overwhelming majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP), including Keir Starmer, to present a radical general election manifesto. If the same had been done for proposals to democratise the party on the lines above, as the Socialist Party argued at the time – appealing directly to the new membership, trade unionists, and registered supporters as in the 2015 and 2016 leadership contests – would the Blairite counter-revolution in Labour have succeeded?

At every stage, however, the leaders of the Corbyn movement, including many of those now involved in the new party discussions, sought to find ‘common ground’ with the capitalist wing of Labour rather than mobilising to remove them from their base in the PLP, the council groups, and the party machine. Yet the interests of the capitalist class and the working-class majority are diametrically opposed. What the working class needs is a party which does not attempt to conciliate them but instead that organises an unbending struggle for its independent interests.

As our feature article concludes, “the question of how a new broad party of the working class is organised and structured is therefore not an unimportant issue, but part of a process of workers becoming aware of their central role in the socialist transformation of society, and of developing the programme, tactics and strategy necessary for achieving it”. The fight for the new mass workers’ party that we need has begun.