HANNAH SELL explains how a misunderstanding of Marxism is shaping the mistaken approaches of most parties on the left towards the basis on which the newly formed Your Party should be organised.

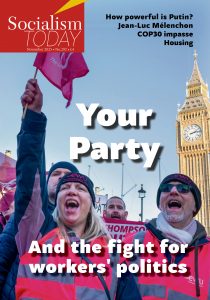

The declaration for a new party announced by Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana began with a bang, with 800,000 signing up in support. Since then, of course, public divisions at the top have dampened some of the initial enthusiasm. However, the party’s foundation is under way. It is at an early stage of development, and its future course is uncertain, but it is, nonetheless, potentially an important step towards a mass workers’ party with a socialist programme.

Socialist Party members are participating in the new party arguing for the approach we think is needed. Often those disagreeing most firmly with us are also members of organisations that consider themselves Marxists. This article looks at some of their arguments to try and help clarify the tasks facing Your Party.

Of course, none of the criticisms we raise justify trying to exclude any left organisation from participation in Your Party. On the contrary, one of the potential great advantages of a new party is an opportunity to debate all of the major issues facing the working class, with all members, including organised trends, having the opportunity to test their ideas against the reality of a living struggle.

The obvious need for a new workers’ party

The Socialist Party was certain that the struggle to create a new party would be on the agenda under Starmer’s New Labour government. We agreed at our National Committee in January 2024, six months before the general election, that “union funding of Labour, and the need for the unions to instead found a new party, will become a sharp debate in the trade union movement” because of the combination of “economic crisis, resurging trade union militancy, widespread support for broadly left or socialist ideas, and the hopes that were raised by Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party”.

It is no surprise that, in contrast, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Britain, which continues to hedge its bets about Labour, concluded in his report on the 2024 general election that it was still yet to be determined “whether the Labour Party can play a progressive role in the struggle for a socialist transformation of society”!

However, they are not alone. It is true that the Revolutionary Communist Party, formerly Socialist Appeal, now say a new party was “entirely predictable” but they were still looking to a left development within Labour just four months ago. In their May 2025 document on Perspectives for Britain, for example, they concluded that only if a “left development within the Labour Party is blocked off for any length of time developments can express themselves in other ways, to be determined by events. Given the intense volatility, it cannot be ruled out that some left formation will emerge”. Similarly, the editor of the Socialist Workers’ Party magazine, International Socialism, Joseph Choonara, declared in June this year that “the creation of a new full-blown left-reformist party, is presently unlikely”.

Clearly, they do not understand that a new party is posed by the objective situation. It is glaringly obvious that the growing hatred of Starmer’s Labour government – and the growth of workers voting for Reform in protest – raises the question of building a new workers’ party. However, to fully grasp that requires understanding the character of the Labour Party, both now and in the past.

Vladimir Ilych Lenin, key leader of the Russian revolution, described Labour in its early years as a capitalist-workers’ party: with a leadership that ultimately defended the interests of the capitalist class, but also a mass working-class base which was able to exert pressure on the leadership via its democratic structures.

Most other Marxist forces in Britain think that remains true today, and that the difference between Labour now and in the 1960s, 1970s or 1980s is only one of quantity rather than quality. The significance of the Blairite ‘counter-revolution’ in the 1990s was lost on them. But the abolition of Labour’s socialist Clause IV and the gutting of the party’s democratic structures via which the working class could exert pressure on the leadership was a fundamental change. Formal trade union affiliation remained, but Old Labour was destroyed and the capitalist New Labour party born.

The backdrop to Blairism’s victory was the collapse of the Stalinist regimes in Russia and Eastern Europe, and the wave of pro-capitalist triumphalism that accompanied it. In that period socialist ideas were marginalised. Levels of working-class organisation were pushed back, and workers’ parties were transformed into pro-capitalist formations.

In government New Labour Mark I acted as utterly reliable representatives of the capitalist class, and as a result they lost five million votes from 1997 to 2010. The idea that Labour was the party of the working class, which most workers voted for, was broken. Only under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership did an element of class politics return, with Labour able to temporarily regain lost ground and get over 10 million votes, with a peak of close to 13 million in the 2017 general election.

Corbyn becoming Labour leader was in a sense an accident of history. The rule changes which allowed non-Labour members to vote in the leadership contest for £3 were designed by the pro-capitalist tops of the Labour Party to break the last vestiges of union influence in the party. However, to their surprise – and to Corbyn’s – in the absence of a mass workers’ party, hundreds of thousands of people, desperate to see a left alternative to the Tory government, signed up to back Corbyn.

Corbyn’s leadership victory offered an opportunity to transform capitalist New Labour into a workers’ party. That, however, would have required mobilising the workers’ movement into a determined struggle to re-democratise Labour and remove the pro-capitalist elements that still dominated its structures. Instead, the new left leadership attempted to compromise with the right of the party, retreating in the face of their demands. The inevitable result was defeat.

Having regained control of Labour, the Starmerites – and behind them the capitalist class – have pursued the driving out of the left from the party with frenzied zeal. However, they cannot destroy the popularity of Corbyn’s anti-austerity programme, nor can they overcome their own deepening unpopularity. Under Blair Mark I the British economy was growing, now it is in a much sicklier state, meaning that acting in the interests of the capitalist class requires more savage attacks on a working class which has begun to re-discover its collective power in the strike wave of 2022-2023, the biggest since the collapse of Stalinism. Against this background it was clear that the question of a new party would be posed in this parliament.

However, the development of a new party or parties in this era is inevitably going to be stormy. The post-second world war era, where capitalism was forced to concede reforms to the working class over a period of decades, is long gone. Today capitalism is a system in crisis and will resist tooth and nail all attempts to wrest concessions from it. The choice between mass struggle and fighting for socialism or capitulating to the demands of the ruling class will be posed for a new party sooner rather than later.

But what kind of party?

The first point in Karl Marx and Fredrick Engels’ Communist Manifesto is that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. In 1848 they wrote that “today society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into great classes directly facing each other: bourgeoisie and proletariat”. They go on to write that “every class struggle is a political struggle” and point to the necessity of “the organisation of the proletarians into a class, and consequently into a political party”.

The experience of the class struggle in the 177 years since the Communist Manifesto was written have led to many further conclusions being drawn by the great Marxists, not least those subsequently made by Marx and Engels themselves. Nothing, however, negates their basic starting premise. In Russia, in 1917, the first time that capitalism was successfully overthrown, it was the working class, despite being a small minority, that was the key social force that led the revolution.

The organised working class is the force in society which has, because of its role in economic production, the potential collective power to end capitalist rule and to democratically run a socialist society that would replace it. And today, far more than in 1917 never mind when the Manifesto was written, society is split into ‘two great hostile classes’, the working class and the capitalist class, with the ‘middle layers’ a much smaller section of society, and increasingly pushed down into the working class and, like the resident doctors, adopting working-class methods of struggle.

The need for the working class to develop its own party is as clear as day, and a vital prerequisite to conquering power. And yet, most of those Marxist organisations in Britain who are now belatedly enthusing about the prospect of a new party see it as “a chance to build a big, left alternative to Labour” (Socialist Workers’ Party), or “a new left party” (Counterfire and RS21). Where the working class features at all it as only one in a list of oppressed groups that a new party should cater for.

Central role of the trade unions

Only a minority of workers are members of trade unions, but they are by far the biggest democratic workers’ organisations in the country, and the first means of defence for workers moving into action. Yet even those that do talk about the need for a new working-class party do not recognise the central role of the trade union movement in creating such a party. Some argue that we don’t want a ‘Labour Party Mark II’, and then point to the problem with the Labour Party being that it has “historically represented the expression of the trade union bureaucracy’s ambitions within the state”. (RS21, Your Party Needs To Bury Labourism, 10 September 2025) Therefore, they conclude in the same article, a new party must break from “labourism”, which means that “while we want to attract the support of trade unions, it cannot be at the cost of member-led democracy. The days of trade union leaders settling arguments behind closed doors and casting votes ‘representing’ thousands of members must be put behind us, along with the unaccountability of leaders and elected representatives to the party as a whole”.

The same fundamental approach is also taken by the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP). Given the support for a new party in the trade unions they are forced to recognise that, “at grassroots level there should be a big push to win support for Your Party especially in the unions that aren’t affiliated to Labour” in their pamphlet, The New Left Party: Seize the Time. However, in the entire pamphlet they say nothing whatsoever about trade union representation in the new party. This is worse than the draft Your Party constitution, which at least says the issue will be thought about over the next twelve months. The SWP’s woeful position is no surprise given that they, like RS21, consider the historic problems with Labour being down to the fact that “the party was set up as the political expression of the trade union bureaucracy, a social layer that negotiates between workers and bosses”.

Contrast this to the approach of the great Marxists on the early Labour Party and its precursors. For example, Engels, in a letter to Plekhanov on 21 May, 1894, says of the leader of the Lancashire textile workers, Mawdsley, “he’s a Tory: in politics a Conservative and in religion a devout believer” but, Engels goes on, “in a quite recent manifesto Mawdsley, who last year was a fierce opponent of any separate policy for the working class, declares that the textile workers must take up the question of separate representation in parliament”. It is, Engels went on, “the branch of industry and not the class that demands representation. Still, it is a step forward. Let us first smash the enslavement of the workers to the two big bourgeois parties; let us have textile workers in parliament just as we already have miners there. As soon as a dozen branches of industry are represented class consciousness will arise of itself”. Not for one minute did Engels confuse the outlook of the leaders with the importance of the working class taking steps towards political independence.

Three decades later Lenin was urging the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain to apply to affiliate to the Labour Party. The Labour leadership’s defence of capitalism was clear to Lenin, but so too was the fact that the big majority of the organised working class saw the party as representing their interests in parliament. Similarly, in 1925 in Where is Britain Going?, Trotsky describes the Labour leaders and trade union bureaucrats as objectively “the most counter-revolutionary force in Great Britain, and possibly in the present stage of development, in the whole world” but nonetheless sees the importance of the Labour Party which had sprung up “as if out of the earth itself”, as the trade unions, “the most unalloyed working-class organisations” in Britain, had lifted it “directly onto their shoulders”.

Trade unions were not the only bodies that played a role in founding the Labour Party. Alongside them socialist and community organisations affiliated, as they should be able to do to a new party today. Nonetheless, the trade unions provided the class ballast that was central to Labour’s strength.

Lenin and Trotsky’s characterisation of Labour was graphically confirmed in the events of 1931. The capitalist class were demanding that the second Labour government implement savage austerity. A narrow majority of the cabinet were willing, but Ernest Bevin, the right-wing general secretary of the Transport and General Workers Union, had to reflect the anger of his members and tell the government in no uncertain terms that the trade union movement would not countenance it. Therefore, in order to drive through their programme, the capitalist class had to split the Labour government, with the Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald resigning and then forming a national government with Tories and Liberals.

Trade union democracy

In 2025 it should be clear to anyone who considers themselves a Marxist that fighting for steps towards a political voice for the organised working class is vital and that, if Your Party is to meet its potential to play a positive role in that process, it needs a federal structure with union representation prominent. It is ludicrous to oppose that on the grounds of the role of the right-wing trade union leaders. Both the SWP and RS21 work in the existing trade unions despite right-wing leaderships rather than set up new ‘red unions’ because they presumably understand that they need to be part of these mass collective organisations via which the working class defends itself in the workplaces. How, then, can it justified to fail to call for those mass collective organisations to also have a political voice?

Of course, the majority of trade union leaders will oppose that, whether by defending the Labour link in the case of the eleven unions that are still affiliated to Labour, or in the 37 that are not, by claiming unions should ‘stay out of politics’. However, for growing numbers of trade union members this is an increasingly important issue. Look at the almost unanimous support for the emergency motion at this year’s Unite conference, initiated by Socialist Party members and others, which agreed to reassess the union’s relationship with Labour if the fire-and-rehire of the Birmingham bin workers went ahead, as it has since done.

We do not favour non-political trade unionism. Disaffiliation from Labour on its own does not take the situation forward significantly. But nor would the unions simply giving money to a new party, without any say in its policies or functioning. Engels rightly pointed to the limits of the leader of the Manchester textile workers thinking only of parliamentary representation for his industry, rather than the working class as a whole, but that was nonetheless a much greater step on the road to building a workers’ party than a union leader just handing over money to a new party. This passive approach is, however, what the SWP and RS21 are calling for.

Of course, that is not to suggest that our aim is to replicate the Labour Party: to create a Labour Party Mark II. Far from it. It is true that right-wing trade union leaders were sometimes able to use the union ‘block vote’ to back the right of the party over the heads of their members. However, that was not pre-ordained, as trade unionists fought to hold their leaders to account. For example, in 1982 Sidney Weighell, right-wing general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen, predecessor union to the RMT, was forced to resign because he broke the democratic mandate of his members. That was the start of a process of radicalisation in the union that led to the election of Bob Crow as general secretary, who helped pioneer the need for trade unions to stand independently in elections beginning under the last New Labour government.

Marxists should fight for every measure possible to ensure the maximum democracy in the new party, including for its MPs and other public representatives to be accountable, subject to recall, and to only take a skilled workers’ wage. We should also fight for trade union votes in the new party to be under the democratic control of trade union members, with delegates elected to represent the union within the Your Party structures held to account. Just as was the case in the early days of the Labour Party, in many unions it is likely to be local or regional bodies supporting the new party in the first instance, rather than unions as a whole. Such local union bodies could be affiliated to local cities or districts of the new party, with representation on city or district committees alongside representation from local party branches.

However, it would be a serious mistake not to take on the fight to win unions as a whole to affiliating to a new party, on the defeatist grounds that the inevitable result would be a party being derailed by the trade union bureaucracy. Are the SWP and RS21 really arguing that it would not be a step forward if a union was to elect a left leadership, a Bob Crow figure for example, that argued in favour of their union affiliating and playing a role in building a new party on clear, class lines?

It’s a struggle!

Marx said that the whole history of society is a history of class struggle. The same is true of the history of building workers’ organisations. The capitalist class have never, and will never, just stand back politely while a workers’ party evicts them from power and builds a new socialist order. It is inevitable that the capitalists will do all they can to sabotage a new party, particularly as it becomes successful. That will include, of course, all kinds of attempts to pressurise and undermine the party from the outside, but it will also include bolstering capitalist forces with a more ‘moderate’ programme inside the party.

This struggle cannot be avoided, but the most effective means to counter it are by making sure that the organised working class has power within the party’s democratic structures, and allowing full freedom for different trends to organise inside the party; allowing Marxist forces with, as Marx and Engels put it in the Communist Manifesto, “the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march” needed for the “conquest of power of the proletariat” which, if they demonstrate that in practice in course of struggle, will win the confidence of growing sections of the working class.

Unfortunately, many others on the left do not understand ‘the line of march’ and, rather than explain the concrete steps that are needed to take the struggle forward, retreat into radical ‘revolutionary’ phraseology. The Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP), as far as they reference Your Party on their website at all, limit themselves to emphasising that unless the new party is “established on the basis of a clear, anti-capitalist, revolutionary programme, it would ultimately fail”. (Ben Gliniecki, RCP general secretary, 19 September 2025) This is without one word on concrete proposals to take the struggle for a workers’ party forward.

It is no different from the approach of the Social Democratic Federation which Engels lacerated for acting “like a small sect” which has not “understood how to take the lead of the working-class movement generally, and to direct it towards socialism. It has turned Marxism into an orthodoxy. Thus, it insisted on John Burns unfurling the red flag at the dock strike, where such an act would have ruined the whole movement, instead of gaining over the dockers, it would have driven them into the arms of the capitalists”. (Interview with the Daily Chronicle 1 July, 1893) Engels is berating the SDF for the abstract, ultimatist approach which the RCP has today. The Socialist Party argues for its programme throughout the movement, including in the new party. We think that it contains the central tenets needed to successfully overthrow capitalism. But that does not mean we discount the importance of steps forward by the workers’ movement because they have more limited programmes than ours.

We never, however, act as uncritical cheerleaders for left leaders. Our role is to put forward the steps needed at each stage. To put it mildly, it is a serious case of uncritical cheerleading to suggest, as Socialist Alternative has done, in their article on the Liverpool Your Party rally, that Zarah Sultana’s speech was “a gigantic political step forward for the left and labour movement in Britain” because she had understood that “socialism is an alternative social, political and economic system to capitalism, which is based on the transformation of the fundamental social relations in society: replacing private ownership of the means of production with democratic public ownership and planning to meet the needs of people and ecology”.

Unfortunately, this is a case of hearing what you want to hear and not what was said. It is certainly positive that Zarah Sultana often references socialism in her speeches, and has declared that “nationalising a few industries isn’t enough, we need democratic control of the economy by workers”. But we shouldn’t fill out her brief remarks with our content, concluding that she agrees with the need to overthrow capitalism and develop a socialist planned economy, never mind that she agrees with the central role of the working class in achieving that. Any more than it would have been correct to draw that conclusion about the very moderate Fabians, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, who, under the pressure of the Russian revolution in 1918 drafted the socialist clause in Labour’s constitution.

Zarah Sultana’s current approach to the structure of Your Party, which has included opposing trade union affiliation, a federal structure, or even a delegate structure, certainly shows that she, like others in the leadership, does not at this stage agree that the organised working class should be central to Your Party and favours a superficially democratic ‘horizontalist’ structure – in which members can participate via online votes, but in practice would leave decisions in the hands of a small leadership who decide what questions are put out for consultation with the membership.

What role for electoral politics?

For the SWP, the central fault line in the new party revolves around the ‘importance’, or otherwise, of standing in elections. Since around 2015 up until the last year or so they dismissed electoral politics altogether, falsely counterposing it to strikes and demonstrations. Recently they have started to stand in a few seats, although like the RCP they have done so by hiding their banner as ‘independents’ rather than stand as socialists, despite both having been offered the use of any of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition’s socialist and working class electoral descriptions. And, in their pamphlet on the new party, they generously concede that “Your Party will stand in elections of course. And its right to do so”.

However, they argue that the new party shouldn’t repeat what they see as the ‘mistakes’ of the Independent Labour Party, which had split from Labour in the 1930s but “was too focused on parliament and not on agitation outside”. And when they say that “the new left party shouldn’t be a Labour Party Mark II”, what they are really arguing is that it should not subordinate “electoral and parliamentary calculations to boosting the confidence and organisation of the working class to fight”.

What does this actually mean? Of course, boosting the confidence and cohesion of the working class should always be primary for Marxists. And it is crystal clear that the socialist transformation of society cannot be achieved by taking over the existing capitalist state machine. A workers’ government would need to break the levers of power held by the capitalist class, beginning by taking over – under democratic workers’ control and management – the major corporations and banks that dominate the economy. That would only be possible on the basis of a mass movement outside of parliament, out of which would certainly develop the basis for a new society with a far deeper, more thoroughgoing kind of democracy than exists under capitalism, along the lines of the workers’ councils or soviets that were key to the Russian revolution.

But none of this gives a scintilla of justification for Marxists trying to evade the role elections in a capitalist ‘democracy’ play in shaping working class consciousness. Of course, it is an objective fact that the capitalist class has historically used Labour governments as a means of holding the working class in check, sometimes successfully pushing through attacks on the working class that would not have been tolerated from a Tory government. It is also an objective fact that, while the first response of the capitalists to the development of a new workers’ party in Britain will be to attempts to undermine and sabotage it, when it starts to win elections they will also attempt to use it in the same way as Labour governments were used in the past or, for example, the Syriza government was used by the Greek capitalists in 2015 (see Socialism Today No.287, May 2025). However, deciding to ignore elections does nothing to change objective reality, but only shows a deeply unserious approach to the struggle for socialism.

Fighting seriously in the electoral arena is a vital aspect of the class struggle. Take the most immediate elections looming in England: the council elections next May. If Your Party conducts a serious campaign in those contests, it could win swathes of councillors and even win control of some councils. If, as the Socialist Party is campaigning for, Your Party leads councils by refusing to implement cuts, and fighting for the resources from central government required to meet the needs of the population, it would have a tremendous effect in boosting the confidence of the working class. Struggle would be on the agenda on the scale of the mass 50,000 strong demonstrations and citywide strike action that took place in support of Liverpool city council under our leadership in the 1980s when it took on the Thatcher government.

Instead, the SWP are currently dismissing this field of struggle – as a prelude to opportunistically turning back in the future – on the basis that stepping onto it will automatically lead to betrayal. This might appear radical, but in reality it is little different to those on the putative right of Your Party who avoid seriously contesting elections in order to concentrate on community organising consisting of food banks and helping the needy, rather than fighting to take control of local councils in order to harness the resources of the local state in the interests of the working class and poor.

All these issues and more will continue to be debated. Far more important than the arguments of different left organisations is the fact that the need for a new workers’ party is being grasped by growing numbers of working class and young people. At bottom, that was what was represented by the 800,000 who initially signed up to Your Party. Whatever the complications a new phase of class struggle has begun.