Rising strike action and economic and political crises are central features of the situation in Britain as we enter 2023. How do we see these processes developing in the period ahead? Below Socialism Today prints the draft British Perspectives document written for debate at the Socialist Party’s national congress in February, which addresses these and other vital issues for the class struggle today.

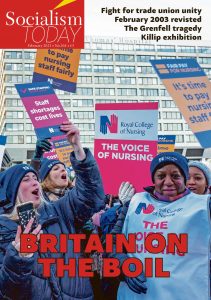

The background to the 2023 national congress is economic crisis, a weak government and, above all, dramatically intensified class struggle. In December 2022 an estimated 1.5 million days were lost to strike action, the highest level for over thirty years. As January 2023 opens, the strike wave is continuing to escalate. It has widespread popular support.

What, however, are the prospects for class struggle beyond the immediate period? As this statement elaborates, the as yet uncertain outcome of the current strikes will be an important factor shaping future developments. But regardless of the results of these battles, we are at the beginning of a new period of increased working-class combativity.

Clear successes for the trade unions in the present disputes would partially relieve the desperate of cost-of-living squeeze and enormously strengthen the confidence of the working class for inevitable future battles. On the other side, even if the current wave of struggle does not lead to clear victories for workers, or if defeats are suffered, it will not prevent new conflicts erupting. The current strike movement marks a turning point, a decisive departure from the previous period of prolonged low levels of struggle.

At root, the reason for this lies with the accelerated decline of British capitalism, against the backdrop of increased instability and crises worldwide. As Marx and Engels explained, we do not have a mechanical approach that class struggle, or events in general, are simply determined by economics. On the contrary, there is a constant interaction between the superstructure – politics, the state, media, culture and so on – and the economic base of society. Nonetheless, the economic foundation of society, and the increasing inability of capitalism to develop the productive forces, is ultimately decisive in setting the broad parameters of developments.

The immediate cause of the current strike wave is clearly the highest level of inflation for 41 years leading to a dramatic fall in real pay. In addition, the shortages of labour in some sectors – particularly HGV drivers – increased some workers’ confidence to strike. Both of these factors exist in numerous countries, but are particularly acute in Britain. However, there are other longer-term, deep-seated difficulties for capitalism worldwide, which Britain is particularly vulnerable to. They will have a profound effect in the next period.

The international context

Internationally, capitalism has entered a new phase of crisis. The IMF predicts that 2023 will be “tougher” for the world economy even than 2022, a year when global stocks and bonds lost more than $30 trillion – the heaviest losses in asset markets since the 2008 worldwide financial crisis. The economies of China, the US, and the EU are all slowing simultaneously. The war in Ukraine continues, and has markedly increased the already existing tensions between the major powers.

The 1990s era of globalisation is now definitively behind us. That is not to suggest that world trade overall has fallen dramatically. On the contrary, for example, the volume of world container shipping reached an all-time high in September 2022. What is past is the period when US imperialism really was, for a short period, a hyperpower. The central feature of ‘globalisation’ was, in reality, the capitalists, particularly US capitalism, restoring profits by taking advantage of the collapse of Stalinism to step up an offensive against the world’s working class.

They were able to do so because of the billion plus additional workers added to the world capitalist economy, coming together with the weakening of workers’ consciousness and organisation. When, for example, Chinese factories began on a large scale to act as assembly plants for Western capitalist companies, with workers paid a tiny proportion of the wages of workers in the US or Europe, it was a powerful means to increase profits and to drive down wages globally. Of course, like all capitalist ‘solutions’, it intensified other problems. It exacerbated the inability of the working class to buy the goods it produces, and helped lay the basis for new capitalist crises.

For a period this was partially overcome with low interest rates and ‘cheap money’. Sections of workers in Britain, for example, were able to spend beyond their means via mortgaging and re-mortgaging their homes as well as accumulating credit card debt. There was an enormous accumulation of debt globally. Even after the financial crisis triggered the ‘Great Recession’, new financial bubbles were created via Quantitative Easing and other measures. Huge state intervention during the pandemic further increased the amount of debt. Today, world debt is equal to more than 350% of global GDP.

Now, however, with inflation soaring globally, central banks are taking the road of ‘quantitative tightening’, desperately trying to squeeze inflation out of the system by reducing the amount of money in circulation. They are compelled to do so, but are deepening the developing world recession. Capitalist commentators are busy debating whether the era of ‘cheap money’ is over for ever. Clearly, it is likely that, under the impact of economic crises, and above all mass movements against their effects, at different stages some central banks will have to reverse their current direction regardless of the consequences for inflation. Inflation, after all, is a ‘tax increase without a vote’, cutting the value of workers’ wages.

However, there will be no return to the previous period of prolonged low interest rates and ‘cheap money’, seemingly without serious consequences, which was only possible in a world situation that has now vanished. The US remains the most powerful capitalist country, economically and militarily, but is in decline, and is progressively more unable to call the shots. China is no longer content to act as an assembly plant for the West, but is an increasingly powerful rival which US capitalism is desperately trying to prevent climbing up the value chain (i.e. developing advanced manufacturing).

Inter-imperialist rivalry, instability and conflict are on the rise. The Ukraine war, with the resulting sharp rise in world energy prices, will not be the last geopolitical event to trigger increased economic turbulence. Nor are geopolitical events the only possible shocks. New financial crises globally, or economic shocks to any of the major economies – not least Britain – can also act to trigger broader economic crises.

Britain’s parlous situation

Against the background of this increasingly fractious and unstable world situation, British capitalism is in a particularly parlous situation compared to other economically developed countries. The 2023 Financial Times annual survey of economists found that more than four fifths of them expect the UK to fare worse than other G7 economies, with GDP shrinking for all or most of 2023. The OECD predicts the UK will be the G20’s ‘worst performer’ bar Russia in the next two years.

There are immediate weaknesses in the British economy that are given by capitalist commentators as explanations – including being heavily reliant on gas with very limited storage facilities, the disruption of Johnson’s Brexit deal, having a high percentage of mortgage holders with time-limited fixed rate deals and, more broadly, having the highest current account deficit of any of the G7 countries; and the fourth highest of the 38 advanced economies that the IMF tracks. A current account deficit shows by how much the total value of goods and services a country’s imports exceed the amount it exports. Imports of course, become more expensive when the currency falls in value.

All of these immediate factors are, however, inseparable from the underlying weaknesses of British capitalism. British capitalism has been at the leading edge of one thing – restoring profits by driving down wages! Prior to the current surge of inflation, in 2020, the median household income per person, in real terms, was lower than the US, Canada, Australia, Germany or France, and – unlike any of them – was already falling markedly. According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, real household disposal income is a third less than the pre-2007 trend. Meanwhile the Sunday Times Rich List shows, for example, that during the pandemic the number of billionaires in Britain grew by 24%, and billionaires’ collective wealth increased by 22%. Today’s anger at the cost-of-living crisis is being enormously fuelled by the preceding long period of wages squeeze, while a few at the top accumulated unimaginable riches.

However, alongside an increase in the share being taken by the super-rich, there has also been an incredible slowdown in the growth in British capitalism’s productiveness. From 2007 to 2016 increases in labour productivity (increases in how much each worker produces) have been virtually zero, growing at a paltry 0.09% a year. The fall in the rate of growth, from the already very low pre-‘Great Recession’ level, is equivalent to an output shortfall of close to 20%. Some capitalist economists have concluded that this is the worst productivity slowdown for 250 years – in other words since the dawn of capitalism! The historical justification for capitalism was its ability to develop the productive forces – industry, science and technique. Today, globally, capitalism is an increasingly sclerotic system, but in Britain it has been incapable of even the tiniest increases in productivity.

Capitalism developed first in Britain, and is particularly decrepit today. Levels of investment have languished below other developed economies for more than forty years. ‘Green’ investment is sixth out of the G7 countries, with only Japan having lower levels. Long-term planning has been jettisoned for making a fast buck – hence, for example, the lack of gas storage facilities. Britain led the international trend to privatise previously state-owned companies, services and infrastructure with little thought to the importance of their efficient functioning for capitalism as a whole.

The results have been particularly starkly revealed in the recent period. For example, the French government was able to force the main energy provider, EDF, to cap price increases at 4%, because it already owned a majority of the company -and has since moved to fully nationalise it. In contrast, consumers’ energy bills in Britain have increased by an average of 80%. Meanwhile, the government intervention to prevent them rising even further, limited as it is, has thrown an estimated £89 billion at the energy companies.

The increased dominance of finance capital globally also went further in Britain than other major economies. Now, however, even Britain’s finance sector is falling behind its competitors. Johnson’s Brexit deal has accelerated this trend, but it is since the 2008 financial crisis that decline has really set in. In terms of market capitalisation the London Stock Exchange has slid to eighth place in the world. While it is dubious how much real economic development it represented, prior to 2008 Britain’s finance sector appeared to contribute to slightly higher productivity increases, but that is no longer the case, even on paper.

Drowning in debt

In Britain, like in other countries, capitalism’s fault lines have been partially obscured by ‘cheap money’. Debt – corporate, government and personal – is at huge levels. As interest rates have gone up, however, that situation is becoming less sustainable. Corporate bankruptcies are already running at a higher level than their post-2008 peak, with an average of 47 shops a day closing, for example, and will go much higher in the course of the next year, as recession bites. Household debt has not reached its 2008 all-time peak, but was still at an enormous 133% of household disposal income in the third quarter of last year. As mortgage rates increase, arrears will become widespread and, despite the banks promises to ‘lean in to help’, repossessions are likely to rise, perhaps dramatically.

Government debt is also at a historically high level. Public sector debt reached 101% of GDP at the end of June, a level last seen in the early 1960s as a consequence of the debt accumulated during the second world war. It is expected to reach 106.7% in 2023-24. In an indebted world this is not the worst – France and Italy both have higher levels. However, the weaknesses of British capitalism, and its increased international isolation, leave it among the more vulnerable of the most advanced capitalist countries to be punished by the markets, as the Liz Truss mini-budget fiasco clearly demonstrated. For now, Tory Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Chancellor Jeremy Hunt have managed to stabilise the situation, but new sharp crises are possible.

Over the next few years, the scale of UK government debt means that the Treasury will need to sell an average of £240 billion of gilts (government bonds) each year for the next five years. That eclipses all previous records, other than the vast borrowing during the pandemic. At that stage, however, the Bank of England bought the majority of them as part of its Quantitative Easing programme. Now ‘quantitative tightening’ means the Bank of England is selling them too! When he was Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney described Britain’s government as being “reliant on the kindness of strangers” to finance its debt. At the time, in reality, the bank he headed was financing the bulk of it. Now, however, his assessment will be accurate. However, it will not be kindness but the profits to be made that will determine whether they will buy up UK government debt.

The possibility of a new disaster in the markets could not be clearer. Such a crisis could potentially have wide consequences. When Truss’s mini-budget trashed the markets it came close to causing a catastrophe in pension funds in particular, which are massively overleveraged, based on huge financial bubbles in the economy. Pension funds have relied on ‘Liability Driven Investments’, which usually involves buying gilts and then, in effect, borrowing up to seven times their value. Those that lend the money demand collateral. In the case of the Truss debacle, as the price of gilts tumbled, more and more pension funds had to sell gilts in order to provide the promised collateral, but were increasingly unable to do so as their price plunged. If the Bank of England hadn’t stepped in and promised to buy long-term gilts, major pension funds would have folded which, like the US subprime crisis in 2007, could have triggered a world financial crisis. The problem has not gone away. The total UK assets covered by Liability Driven Investments has exploded over the last decade from £400 billion in 2011, to £1.6 trillion in 2021.

Tories strike tactics

The problems of British capitalism place real limits on the room to manoeuvre for any capitalist government, but especially the current Tory government, which has lost virtually all authority, and is riven with splits. Sunak and Hunt’s coming to power represented a certain limited stabilisation, at least compared to the Truss debacle. Nonetheless, from day one Sunak has led an extremely weak government. Throughout the second half of 2022 it was like a rabbit in headlights, unable to respond effectively to the rising tide of strikes. Their seeming intransigence does not stem from a position of strength but from their complete inability to come up with, never mind agree, an effective response.

Undoubtedly, the government and the employers hoped that financial hardship would result in those strikes that started first – particularly the CWU and RMT – starting to crumble, allowing the imposition of management attacks. However, the resounding RMT re-ballots – which revealed an increase in union membership, a turnout of 70%, and an average ‘yes’ vote of 91% for continued strike action – have shattered the Tories hopes on that score. Nonetheless, that danger can exist in the future, and our demand for the whole trade union movement to build a massive strike solidarity fund, in order to prevent any group of workers being starved back to work, and to make it easier to escalate the action, remains very important.

At this stage, however, the determination of the strikes has forced the government to ‘blink first’ and abandon its unwillingness to even discuss pay with striking trade unions. Large sections of the establishment have been urging them to do so, rightly fearing that their extremely brittle intransigence would result in the government shattering under the pressure of the strikes. It is fear of the deep, radicalising effects of a strike wave forcing the Tories out of office that is motivating serious capitalist commentators – including editorials in the Financial Times and Evening Standard – as well as the head of Britain’s military, Admiral Tony Radakin, to attack the government’s approach. Pressure has also been building in the Tory backbenches to make concessions to the nurses in particular.

However, so far the government’s change of stance amounts to a ‘big stick’, in the form of introducing new draconian ‘minimum service’ anti-union legislation to parliament, and only the faintest whiff of ‘carrot’, with some vague talk of an unconsolidated lump sum which, outrageously, they are initially trying to tie to ‘productivity increases’. Most workers will treat this alleged concession with the contempt it deserves. Let’s remember that before Christmas 2022 much was made about the SNP government in Scotland being willing to make concessions, in contrast to the Tories, and thereby avoiding strike actions by nurses there. The average wage increase of 7.5%, however, was rejected by RCN members in Scotland by a massive 82%!

As we have demanded, the trade unions should meet the Tories’ combination of showing both weakness and contempt for workers by stepping up the struggle, and naming the day for every trade union with a live ballot to strike together, as a major step towards a 24-hour general strike. Short-sighted as they are, the Tories are at least dimly aware they risk provoking such a response, hence their hesitation about introducing new anti-union laws up until now. They have seen how their sister party in Ontario, Canada was forced to withdraw new anti-strike laws over the course of a weekend in the face of the trade union movement threatening general strike action. The workers’ movement in Britain should take the same approach. Such a day of co-ordinated strike action should of course demand inflation-proof pay rises for all, but also withdrawal of the new anti-trade union laws and repeal of the old, and emergency action to save our NHS.

Our demand for a 24-hour general strike is inherent in the situation, and serious steps towards it may take place even before our National Congress. At the time of writing 1 February has been announced as a TUC day of action, with the possibility of coordinated strike action on that day. However, this does not mean there are no obstacles to coordinating the strikes. There is a general enthusiasm among workers to ‘all strike together’ but there are also pressures in the other direction. Pat Cullen, general secretary of the Royal College of Nursing – which is not affiliated to the TUC – has opposed coordinated action, saying that “Our dispute is about the nursing profession and doing a deal for nursing is my only priority.”

There is a material basis for skilled sections of workers, like the nurses, wanting to fight apart from the cleaners and domestics in the same hospitals, never mind the broader working class. The same is true of other sectors such as the train drivers, who are mainly organised in ASLEF, and the station staff who are overwhelmingly in the RMT. Encrusted union officialdoms, even sometimes those on the left, lacking confidence in the working class, can have an interest in playing on those divisions in order to defend their own material interests.

Beyond these issues, the right-wing leaders of the trade union movement share the capitalist class’s fears of the effect of generalised action. At the start of 2023 the new TUC general secretary, Paul Nowak, tried to dampen down any talk of a general strike. He said to the Financial Times, for example, that “such a mass walkout would fall foul of trade union legislation, and would make little sense to groups as disparate as teachers and physiotherapists who were worried about pay, but hardly inclined to militancy.” There is no doubt that much of the TUC leadership prefer that protests such as on 1 February are no more than another polite lobby of parliament. The right’s fear of coordinated action has the same root as our campaigning for it. Fundamentally, they cannot conceive of the working class taking power and are desperate to avoid taking responsibility; they see the limits of the trade union movement’s role as putting pressure on the capitalist class and capitalist politicians. For us coordinated action is not a question of principle. Sometimes the ‘uncoordinated waves’ of strikes in the recent period can be effective in maximising disruption while minimising loss of pay.

However, ‘all striking together’ would have a much greater effect in increasing the cohesion and understanding of the working class as a whole about its potential power. Millions having taken part in a 24-hour general strike which led the Tories to call a general election would undoubtedly make it harder for right-wing trade union leaders to hold back struggle under a future Labour government, and the right-wing leaders understand that. Despite the obstacles, however, the mood for coordinated action is very strong and, under its pressure, meetings of representatives of all the TUC-affiliated unions with live ballots have taken place, and have begun to discuss the possibility of a day of coordinated strike action in February. Under pressure from below even the most right-wing trade union leaders can be forced to take militant action which they had previously considered unthinkable.

Trade unions are basic organisations of the working class through which millions of workers can defend themselves against their employers in the workplace. However, the constant attempts of the capitalist class to incorporate the union tops into the capitalist state mean that there is always an internal struggle within the trade union movement. On one side stands the pressure of the mass membership, who the union tops ultimately depend on for their positions. On the other, the huge pressure exerted by capitalism on all representatives of working people, especially in the unions. The counter-pressure of the most militant trade union activists being organised in democratic trade union broad lefts is therefore vital.

Trade union activists’ outlook

How strong is that pressure from below at the moment? Already, over six months of struggle, an enormous amount has been learned by a new generation, particularly by the workers who are at the forefront of the strikes. That does not mean, however, that no marks of the previous decades remain. Although wave after wave of workers are joining the strike movement, there are also sizeable sectors who have not managed to overcome the anti-union turnout thresholds. The vast majority of workers who are on strike have never been out before, including many of those who are now stewards and reps.

The British working class is still at the beginning of a steep learning curve from which a new generation of trade union militants are being formed. At this early stage, however, some of the traditions of the past have not been fully rebuilt. In most cases pickets are seen as important but symbolic protests, rather than democratically organised mass picketing aimed at persuading workers not to cross and enter the workplace. The national strikes have also generally not been indefinite at this stage.

Clearly, with a more farsighted and determined leadership, some of the strikes could have gone much further than they have so far. For example, if the TUC had led a serious campaign to demand that the whole of the workers’ movement builds a mass strike fund to prevent any group of workers being starved back to work, it could have already raised confidence for key sectors to move to all-out action. At the same time, we recognise that, given the obstacles at the top, and the still early stage of the rebuilding of the workers’ movement, the outcome of this wave of struggle remains uncertain. While decisive victories are possible, draws and even defeats can also not be ruled out.

It is possible that the government could end some of the strikes with a combination of a lump sum and improved pay offers for next year, even if they are objectively pay cuts given inflation levels. This could, in some cases, mean imposing the deals in opposition to the unions, but without effective union action being organised against it. In others, workers may choose to bank what they’ve won, even if it is inadequate, and prepare for the next round. Depending how things develop at a certain stage, in some disputes, it could be necessary to retreat in good order and prepare for the next battle, rather than suffer a serious defeat.

Particularly for the workers who are facing fundamental attacks on their terms and conditions, what will be essential is ensuring they come out of this with their unions’ fighting capacity intact. However, even if the outcomes of some of the strikes are setbacks, broad sections of the working class will draw the same conclusions as Bob Crow, late general secretary of the RMT, that “if you fight you won’t always win, but if you don’t fight you will always lose”. Already, numerous strikes, particularly some of those in the private sector, have demonstrated that workers can win big victories.

Whatever the outcome of this wave of struggle, there will be no return to complete calm. Instead, it will prepare the ground for future battles. These will inevitably have a different character than this first phase, both because of the experience that has been gained, but also because of new circumstances. In a recession, with workplaces closing and unemployment rising, mass workplace occupations can be posed. And, while developments in the workplaces and trade unions are key, we also have to be prepared for all kinds of other eruptions of struggle.

The first glimmerings of student protests against the cost-of-living squeeze are currently developing, but could take place on a much bigger scale, like the movement that developed in Southern Ireland in 2022 in response to the planned 2.8% rise in student maintenance loans – which is more than a £1,500 real-terms cut. New Black Lives Matter demonstrations, movements against climate change, mass campaigns in opposition to violence against women, community campaigns against evictions, protests to defend the NHS, and much more are inevitable.

Our role is always to participate in and help build those movements, but above all to put forward a programme to take each movement forward. The essence of our programme: that we fight for every step forward but that a prerequisite for ending racism, overcoming women’s oppression or halting climate change is the overthrow of capitalism, and that the working class is the key force to achieve that, will be understood by far wider layers today than at any time for many decades as a result of having seen the working class begin to show its potential power in the current trade union struggles.

The trade unions only organise a minority of the working class, but they remain its basic, core organisations because they are the first line of defence for its collective class interests. Capitalist commentators try and dismiss the trade unions’ strength in the twenty-first century, by comparing it to the much higher level of trade union membership in the 1970s. In 1979, for example, 53% of workers were union members. After the defeats of the previous era, while the fundamental strength of the working class remained intact, in 2020 only 23.7% of workers were members of trade unions.

However, the current union membership levels are not atypical historically. The much higher levels in the 1970s were based on an exceptional situation and class balance of forces. In 2021, trade union membership was 6.5 million, and was already rising before the current strike wave, increasing year-on-year for the four years up to 2020, and has certainly accelerated since. This has included the beginnings of union organisation in previously unorganised sectors, like the Amazon warehouses. While stable levels of trade union membership like those that existed in the 1970s are not on the cards, there is no direct correlation between union density and the scale of struggle.

The number of stewards was also much higher in the 1970s. In 1980, there were 328,000 workplace representatives, of whom 174,000 were in the private sector. By 2004 that figure had fallen to 128,000, with only 56,000 in the private sector. In the eighteen years since there is no doubt that the number of workplace representatives fell much further, particularly under the impact of the 2016 anti-union legislation, which cut rights to facility time for trade union duties. Unison, for example, the biggest public sector union with 1.3 million members, estimated in 2021 there were only 12,000 members active in its structures.

However, the number of shop stewards was also relatively low – despite high union membership – in the 1960s; it was the surge in struggle which forged a new generation of workplace leaders, leading to a doubling of the number of shop stewards in manufacturing between 1966 and 1976. The same process has begun today. While union membership may fluctuate along with the rhythm of struggle, the new generation of fighters that are beginning to gain experience now, have the potential to transform the trade union movement.

We have a vital role to play in helping to cohere the new forces currently joining the trade unions into consistent fighters to transform their unions, above all by recruiting as many as possible of them to our party. The beginning of the development of combines in Unite, under the leadership of Sharon Graham, has the potential to aid this process by bringing together stewards across particular sectors. Trades councils, often little more than empty shells in recent decades, could now start to take on life and coordinate struggles at a local level.

In addition, the National Shop Stewards Network, with nine unions affiliated to it, has the potential to be filled out and play a critical role in the next phase of struggle. Also important will be the development of left organisations within specific unions, campaigning for fighting policies under the democratic control of the membership, including calling for trade union officials to be regularly elected, subject to recall by their members and paid a worker’s wage.

Prospects for the general election and beyond

It is not yet clear when the next general election will be. It is possible that the Sunak government will manage to stagger on until the last possible moment, with the election towards the end of 2024. However, it could fall apart in office well before then, resulting in a general election this year. Splits in the parliamentary Tory party could develop explicitly around issues relating to Sunak’s inability to respond effectively to the strikes. On the NHS, in particular, they are already developing. More Tory MPs switching to the Labour benches is entirely possible. A new market crisis could also trigger a dramatic acceleration of the Tories’ implosion.

However, it can also be other issues, superficially unrelated to the strike wave, which lead to a new high-pitch of rebellion by Tory MPs. The Tory right keep demanding ever-more brutal measures against refugees, and threaten to hold Sunak’s feet to the fire to ensure he carries out his utopian and pointless pledge to remove most EU-derived laws from the statute book by the end of the year. If it is even partially implemented this will further exacerbate the problems of businesses, particularly smaller businesses, which trade with the EU. Meanwhile, the slightest hint of moving towards a closer relationship with the EU, which the majority of the capitalist class badly wants, leads to a renewed hysterical outcry from a swathe of the Tory backbenchers. Despite the improved ‘mood music’ between the British government and the EU, the problems of the Northern Ireland protocol have not been resolved and are likely to flare up again.

In reality, even if the issues which most bitterly divide the parliamentary Tory party appear unrelated to the economic weakness of British capitalism or to the class struggle, this will not actually be the case. The complete breakdown of Tory party discipline is ultimately as a result of the increasing hatred for the party among wide sections of the working and middle class. Facing electoral catastrophe at the next election, many of them can no longer see much point in trying to maintain even a façade of unity. The Tory party was once among the most successful capitalist parties on the planet. Its hollowing out, over many decades, has reflected the decline of British capitalism and its increasing failure to meet the needs of the majority.

The Tories have been in power for twelve years now but during that period, even at their strongest, their support and social base has been extremely weak. Initially, in 2010, they were only able to limp back into power as part of a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. They won a majority in 2015, but with the support of only 24.4% of the total electorate. This was the lowest share for any majority government since the introduction of universal male suffrage in 1918. The savage austerity they have implemented has deepened hatred towards them among wide layers of the working class.

Membership of the Tory party fell to 150,000 in 2012 – compared to an estimated three million in the 1950s – and hasn’t made it back to 200,000 at any point in the decade since. It was claimed that Johnson’s right-wing populism won a new generation of workers to the Tories. In fact, while a limited number of workers did lend the Tories their vote in 2019, Tory party membership only increased to 185,000. Even allowing for higher than average death rates, given the age of the Tory membership, no more than 50,000 people – 0.1% of the population – can have decided to waste £25 on joining. Now, after three leaders in the space of six months, after the pandemic and the current cost-of-living crisis, even the limited, shallow, increase in support that Johnson achieved in 2019 has shattered. There is a widespread feeling that everything in Britain is broken, above all the NHS, and that no one can afford to live; and the Tories are to blame.

It is extremely difficult to imagine what Sunak, or any Tory leader, could now do to significantly dent this mood. Therefore, while all elections represent just one moment in time, and outcomes are therefore uncertain, by far the most likely result is Labour leader Keir Starmer becoming the next prime minister, possibly at the head of a Labour government with a large majority. The main motivation for voting Labour will not, however, be enthusiasm for Starmer or his programme, but rather that they appear the only viable means to get the Tories out.

If the Tories do manage to limp on, more or less in one piece, until the general election, they will fragment further once they are out of power. Already, in December last year, Nigel Farage’s Reform Party – with him having ‘retired’, at least for now – was being highlighted by the capitalist media after reaching 7% in the polls, clearly indicating the space for a right-wing populist party to emerge strengthened from the Tories’ wreckage in the next period.

The most important factor that would weaken such a development is the building of a new mass party of the working class. A tiny glimpse of the effect such a party could have was shown in the 2022 Erdington by-election when, even in the difficult circumstances of the immediate impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, TUSC was able to come third, pushing the Reform Party into fourth place, compared to the 2019 position when, standing as the Brexit Party, they came third with 1,441 votes.

Capitalists looking to Starmer’s Labour

For the big majority of the capitalist class, a Labour government would now be a huge relief. There are several reasons why. They include Starmer’s intention to increase alignment with the EU, for example by adopting the same standards for food and agricultural products as the EU, which would have the potential to at least partially ease the problems of the Northern Ireland protocol. However, the overwhelming reason that they are looking to a Labour government is that it would be able to oversee attacks on the working class more effectively than this broken Tory government.

Historically, when Labour was a capitalist-workers’ party, the capitalist class repeatedly relied on the pro-capitalist leadership of the Labour Party to use its authority as the party of the working class to implement unpopular policies in government. The character of the Labour Party was fundamentally transformed into an out-and-out capitalist party in the period after the collapse of Stalinism. Corbyn’s leadership was a brief opportunity to begin its retransformation, but this was not realised. Nonetheless, it still has a residual place in mass consciousness as the party ‘for workers’, not least because of the propaganda of the capitalist media to paint it as such.

Starmer has ruthlessly re-established an iron grip over the party apparatus for capitalist interests, while making every imaginable statement to demonstrate unequivocally that his government would act loyally in the interests of the capitalist class. This includes his declaration that he, like the Tories, would attempt to block a new referendum on independence for Scotland. Over time, this will further fuel support for independence in Scotland among the working class. In Wales too, support for independence has risen in recent years under the Tories, albeit from a much lower level than in Scotland, and could grow further as discontent with Starmer’s New Labour grows.

Nonetheless, in the short term a Starmer-led government would undoubtedly have more ability to ‘sell’ cuts to workers’ living standards, etc. more effectively than Sunak does. Firstly, because, at least in the initial phase, there would be widespread hopes that Starmer was going to be a least some improvement on the last twelve years. Crucially, sections – in fact probably a big majority – of trade union leaders would attempt to hold back struggle by arguing to give Labour ‘a chance’ and point towards any reforms they promise, however, limited – such as the repeal of some elements of the anti-union laws. This is the significance of Paul Nowak’s statement on becoming TUC general secretary that he understood Labour “can’t turn on the taps from day one”.

However, there would be no prospect of any prolonged honeymoon for a Starmer New Labour government, and its ability to hold back struggle would be shallow and limited. Labour today is not seen by workers as the party that represents their interests in the way that it was historically. At the same time, it would preside over a much more difficult economic situation than New Labour inherited in 1997. Even if, as is far from guaranteed, Starmer is lucky, and the worst of the developing recession has passed by the time Labour takes office, the economic situation will be dramatically worse than in 1997, when the economy actually grew by 4.9%. Undoubtedly the capitalist class will still be demanding austerity in its varying forms given the accumulated weaknesses, including the level of government debt, facing British capitalism.

Most importantly, the workers’ movement is in a very different state from 1997. At that stage, under the impact of the collapse of Stalinism, capitalism was widely accepted as the only viable alternative and the workers’ movement was in retreat. Today, while the consequences of the collapse of Stalinism have still not been entirely overcome, we have entered a new era of heightened struggle. Strikes have reached a level not seen since then. And Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party represented a first attempt in this era to build a mass political alternative to the pro-capitalist parties. Due to the weaknesses of its leadership it has been defeated inside Labour. Today, left candidates for Labour’s NEC get votes at the puny levels they got under Blair. Nonetheless, in society the popularity of Corbyn’s programme showed a search for left, ‘socialistic’ ideas among broad sections of the working class and especially youth. Regardless of the role we play, this will prepare the ground for massive opposition developing to a Starmer Labour government, which in turn will intensify the capitalists’ crisis of political representation.

Fighting for a new workers’ party

However, what we do after a general election and also, vitally, in the run-up to it, can make a considerable difference to the speed of developments afterwards. At this stage we are virtually alone in raising the need for the working class to build a new party to represent its interests. On picket lines this idea usually gets a very enthusiastic response. But even the most combative of the national trade union leaders are as yet unwilling to engage with the issue. That does not mean that trade union leaders are openly campaigning for Labour. Generally speaking, even those that would like to recognise that their members’ anger and frustration with Starmer’s pro-capitalist stance would make it very unwise to do so. Instead, they rely on implicit support for Labour couched in terms of attacks on the Tories.

The Enough is Enough campaign, launched by the general secretaries of the RMT and CWU, now has the official support of the RMT, CWU, UCU and FBU trade unions. Over 500,000 people are reported to have signed up. Most did so looking for a way to show their support for the strikes, and for an alternative to Starmer’s Labour. In reality, the campaign shows the potential for a new mass workers’ party. However, this is not how it is conceived by its founders. At the 2022 RMT AGM, Mick Lynch was to the fore in opposing a motion from Coventry RMT which argued for support for Jeremy Corbyn standing independently in the general election, to back “pro-trade union, anti-austerity candidates in local and general elections” and, lastly, to approach the recently disaffiliated BFAWU bakers’ union and Unite to organise a conference to discuss the “historic crisis of political representation facing the working class”. Mick also argued in favour of a motion withdrawing official RMT representatives from the TUSC steering committee, if it continued to stand candidates in elections. Meanwhile, the CWU remains affiliated to the Labour Party.

Nor is it by chance that the only explicitly political body on the Enough is Enough sponsors’ list is the Labour-linked magazine Tribune – despite the Green Party having voted at their October 2022 conference to affiliate to Enough is Enough. Mick Lynch and other figureheads of the campaign have repeated clearly that they see its role as putting pressure on Labour to act in the interests of the working class, rather than as a first step to building an alternative to it. As a result, notwithstanding the appeal of it having the leaders of trade unions at the forefront of the struggle heading it, Enough is Enough is not fundamentally different to the numerous previous campaigns of this type, including Corbyn’s Peace and Justice Project, the Peoples’ Assembly, UK Uncut, the Coalition of Resistance, and more.

While the consciously pro-Labour approach of the Enough is Enough initiators is not replicated among all trade union leaders, unfortunately none at this stage are arguing for clear steps towards the trade union movement standing its own independent candidates, never mind building a new party. The general secretary of Unite, Sharon Graham, has, however, been prepared to sharply criticise Labour, and Unite withdrew funding from Midlands Labour council candidates over the Coventry bin strike.

The campaign she has initiated, ‘Unite for a Workers’ Economy’, has produced some effective agitational material and aims to organise “direct action” by community campaigners. Nonetheless, the campaign does not currently address, never mind call for, the question of those community campaigners, alongside striking workers, deciding to stand in elections. There is a danger that the effect in practise – even with a different starting point – could, like Enough is Enough, be limited to campaigning to put pressure on pro-capitalist politicians.

But while there are not yet moves from the tops of the unions towards independent working-class political representation, that does not mean that shifts can’t take place under pressure from below, including some kind of ‘workers’ list’ for the general election. We have to take every opportunity to campaign for steps towards a new party, including such a list. Corbyn, who will certainly not be allowed to contest his seat for Labour, could still stand independently. Other deselected or expelled Labour lefts standing is also possible.

Most importantly, under pressure from below, some trade unions could take steps to stand or support candidates outside of Labour. With an incoming Labour government presiding over austerity, even a small bloc of independent working-class MPs would act as a powerful pole of attraction and could rapidly gain support. However, if no more authoritative coalition is in place before the general election TUSC is aiming to act as the biggest possible umbrella bringing together a slate of trade unionists, socialists and community campaigners. Achieving this would be an important lever for the development of a new party in the next period.

Developing socialist consciousness and our role

The present strikes are only the latest experience that is forging the outlook of the new generation. Growing up in the era of the post-2008 Great Recession, they have only experienced capitalism in crisis. Then came the pandemic.

Opinion polls show that voters reaching 40 today are considerably more left-wing than when they were 20, a reversal of the ‘tradition’ of moving to the right with age. With capitalism offering them no prospect of a secure home, a well-paid job, or halting climate change, the majority are looking for an alternative to the left. At the same time, for the first time in a generation, the central role of the working class as a force with the potential to achieve fundamental change is beginning to become apparent.

However, at the moment, with the majority of even the left trade union leaders limiting themselves in the main to making demands for reforms from the existing system, we are alone in putting forward a clear programme for the transformation of society. On that basis we can win growing numbers to our party now. However, in the coming period, we will see huge struggles which will create the potential to win mass support for our ideas. The work we are doing in the current wave of struggle is vital preparation for what lies ahead.