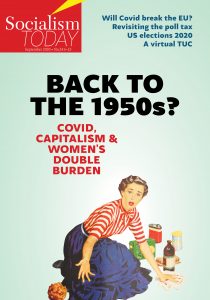

An absorbing new book looks at the changing patterns of women’s work in Britain since the industrial revolution. With Covid-19 potentially marking a new pivotal moment in the history of women’s employment, it could not have been published at a more opportune moment, writes CHRISTINE THOMAS.

Double Lives: a history of working motherhood

By Helen McCarthy

Published by Bloomsbury, 2020, £21

There is hardly any aspect of society that has not been seriously impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. One of its main consequences has been to magnify and exacerbate all of the existing inequalities in capitalist society. The interplay of class and race, for example, has influenced who catches the virus, its severity, and how likely people are to die from it. The same factors determine who suffers from the economic fallout.

The interaction between class and gender inequalities has also been highlighted and intensified. While it’s true that men with coronavirus are more likely to become seriously ill or die, women – working-class women in particular – are more likely to work in areas where there is a greater exposure to Covid-19. They have been 30% more likely to be furloughed, 47% more likely to have lost their jobs, and 50% more likely to have had their hours cut.

Just as women were disproportionately affected by the austerity that followed the 2007-08 financial crisis, the double disadvantage that working-class women already suffered in capitalist society before Covid-19 struck – treble for black, Asian, and ethnic minority women – places them at the sharp end of the post-pandemic economic devastation that looms. A recent study by the University of Sussex reported that lockdown had pushed some women’s lives back to the 1950s. While an exaggeration, there is no doubt that decades of hard-won gains are at risk. Exactly how far back they will be rolled depends on the level of resistance the working class is able to wage.

Reading Helen McCarthy’s well-researched and detailed account of working mothers, one thing stands out: the extent to which social attitudes have been drastically transformed over the years – although without the corresponding structural changes in society. This has led to the contradictory situation in which women’s needs and aspirations constantly clash with material reality.

Prior to the pandemic, 75% of women with dependent children were in paid employment – up from 60% in the early 2000s. This is a far cry from the estimated 13% of married women in work in 1901 or the 10% in the interwar period. As McCarthy points out, working motherhood went from being an unavoidable ‘social evil’ for widowed and abandoned women, or women whose husbands were unemployed, disabled or in desperately low-paid and irregular work, to becoming a social norm that few people query.

While, up until the second world war, married women were barred from many jobs – in the post office, civil service, education, local authorities, etc – by the 1990s, employers and the New Labour government were using the stick and the carrot to push even single parents into the workforce. This suited the capitalists’ need for cheap flexible labour and the government’s desire to slash spending on welfare benefits. This historical process represented a dramatic shift in gender employment patterns, and has hugely impacted women’s lives and ambitions, as well as wider social attitudes.

Entrenched, historic oppression

However, it is equally striking how entrenched and enduring other social features have been. In making the point that a section of working-class women have always worked outside the home, spurred on primarily, although not exclusively, by economic necessity, McCarthy looks at the kinds of jobs women have carried out over the years, and here it becomes clear just how little has changed for working-class women in particular. They have overwhelmingly been employed in sectors of the economy that are extensions of the caring and domestic work they have traditionally carried out, unpaid, in the home. Consequently, those jobs have been devalued and underpaid.

So, women became textile workers in the mills of Lancashire, went to work in laundries and were employed as seamstresses. They became cleaners and worked in food-processing factories. As the welfare state expanded, they took on the roles of teachers, nurses, midwives, health visitors and social workers. And today, during the pandemic, those risking their lives on the frontline in the hospitals, care homes and supermarkets have been predominantly women – two thirds of all keyworkers, 79% of healthcare workers – overwhelmingly on poverty wages – 2.6 million earning less than £10 an hour. In the years since the industrial revolution, the interaction of ideology, capitalist profit needs, male workers’ fear of competition for their jobs, and the historic gender division of labour in the home, has ensured that gender workplace segregation has continued until the present day.

Double Lives looks only at working mothers in capitalist society, beginning in the early Victorian period. As such, the book does not consider the origins of women’s second-class social status and the oppression they have endured because of their gender. During the recent Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality and racism we have often explained, quoting Malcolm X, that you can’t have capitalism without racism. Capitalism and racism arose in tandem, with the emerging capitalist class employing racist ideology to justify the slave trade that enabled capital to be accumulated for the development of the broader capitalist profit system.

Women’s oppression, however, predates capitalism – its roots going back thousands of years to when societies first divided along class lines – with an exploiting class having ownership of the means of producing wealth, and an exploited class of slaves, peasants, etc. As an integral part of that process, women’s role in society became primarily a private one within the family, bearing and raising the future generation and looking after the household. Women of the ruling class were considered the property of their fathers/husbands, who were expected to control their sexuality, through the use of violence if necessary. This second-class status became enshrined in law and reinforced through ideology. (See: Engels and Women’s Liberation, Socialism Today No.181, September 2014)

So, women’s inequality did not originate with capitalism but, as a system, it built on and took advantage of that existing inequality for its own economic, social and political interests. It has been used to justify paying women lower wages in order to increase profits; to offload onto women in the family the burden of public-sector service cuts; to blame women for the poor health of children and make them scapegoats for social problems, such as youth crime, drug taking and truancy; to turn women’s bodies into a commodity, directly through the sex industry and indirectly through advertising and the beauty industry, etc; and to divide men and women, especially in the workplace, to prevent them from uniting to fight exploitation and the capitalist system which breeds it.

Unequal division of labour

With Covid-19, the inequalities that women have experienced historically – at work, within the family and in wider society – have combined to create specific problems during lockdown, and potentially much bigger ones for the economic disaster that looms. McCarthy’s book shows that, notwithstanding the huge change in social attitudes towards women with children working outside the home, the assumption that they have the main responsibility for childcare and domestic chores remains deeply embedded in society. Before Covid, women carried out, on average, 60% of unpaid work in the home. This unequal division of domestic work has been magnified under lockdown.

Although surveys have found that men who are furloughed or working from home have increased the time they spend looking after children and doing housework, women average four times more than men. The University of Sussex survey revealed that 70% of women were doing all or most of home schooling. Sixty-seven percent felt like the default parent children went to whenever they needed anything; mothers working from home were twice as likely to be interrupted as fathers. As one woman said to the Guardian, if her house was the school, she was the cook, cleaner, caretaker and teacher. All of this has led to exhaustion and stress, and contributed to mental health problems, which have been higher among women than men during the pandemic.

This unequal gender division of labour in the home has determined the kind of jobs that women with children have been employed in. Both of these factors are already impacting on women’s job prospects and are likely to have an even greater effect as the economic crisis really starts to bite. Women went into lockdown with the disadvantage of a gender pay gap of around £9,000 a year, on average. Struggles by women and the working class as a whole led to legal gains for women in the 1970s. But many employers immediately attempted to circumvent the Equal Pay Act through regrading, for example, where women and men were not doing the same job so their pay could not be compared.

Even though the legislation was extended in 1983 to cover work of ‘equal value’, the fact that men and women working for the same employer continue to be segregated in mainly ‘female’ and ‘male’ sectors means that huge battles still have to be waged to secure pay equality. Female Asda shop workers have been involved in a long legal fight to secure equal pay with male distribution workers. The historic victory of 8,000 predominantly low-paid women working for Glasgow city council following militant strike action in 2018, backed up by solidarity action from male bin workers, is a better model for how equal pay can be won.

Because of caring responsibilities, 40% of women are in part-time work where wages tend to be low. Surveys have shown that most would prefer to increase their hours or work full-time but are not able to do so because of a lack of affordable childcare. When schools closed because of Covid, in some households, decisions had to be made about who would continue to work and who would stay at home and look after the children. With working-class women generally earning less than a male partner or working fewer hours, in most cases it made more sense economically for the woman to stay at home. Of course, in lone-parent households there was no choice to be had.

Even when the schools return, it is unlikely to be on the same basis as before Covid. What happens if they are not open full-time or the start and finishing times are staggered? Or if there are more local lockdowns like the one in Leicester? What will happen to the jobs of women who do not have flexibility with their working hours or for those forced to be at home to look after the children? When employers are deciding who to take back after furlough and who to make redundant, women with caring responsibilities are likely to be penalised because they are viewed as unreliable. According to a Pregnant Then Screwed questionnaire, 50% of working mothers said that lack of childcare had a negative impact on how they were perceived at work.

Capitalist ideology

Double Lives shows how attitudes and policies on childcare have been shaped to the detriment of working mothers throughout capitalism’s history. For families of the capitalist class in the 19th century a breadwinner husband and a stay-at-home domestic wife became a sign of wealth and respectability. The economically dominant class also influences the ideas and values in society, and this ‘bourgeois’ family form became the norm to which all classes aspired.

Working married women became socially unacceptable: their ‘natural place’ was in the home nurturing the children and attending to their husband’s emotional needs. Working-class mothers who had no choice but to work if their families were not to starve or end up in the workhouse were either forced into sweated home work or left to sort out their own childcare, making informal arrangements with family members or neighbours. For many women today that is still how childcare is organised. Covid has revealed just how much women rely on grandparents who, because of social distancing rules, were no longer able to look after their grandchildren.

Capitalist ideology regarding women’s role as homemakers and nurturers continued to dominate during the interwar period. Reforms were posed as bettering women’s ‘natural role’ through improvements in maternal and child welfare. The Beveridge model for the post-war welfare state was also predicated on a situation where most married women would be full-time housewives. Local authority nurseries actually decreased from 40,000 in 1950 to 28,000 in 1955, and 21,500 in 1963. The criteria for eligible children were tightened towards the end of the 1960s so that day nurseries became a public service accessible almost exclusively for ‘problem families’.

While nursery classes were expanded, these were seen as mainly assuming an educational role for young children, not as a means of enabling women to participate in the workforce. In 1965, there were places for just 3% of 3-5-year-olds. In 1977, as spending cuts hit after the 1974-75 economic crisis, only one in 30 pre-schoolers had access to a council day nursery. Places in nursery schools were mostly part-time, typically 2-3 hours a day, of limited use for working mothers.

The only time the state really stepped in and took collective responsibility for childcare was during the first and second world wars, when central governments subsidised day nurseries. With men fighting at the front, women’s labour was desperately needed, especially in the munitions factories, but also in transport and other sectors. Although the quality of nurseries varied, they nevertheless enabled mothers to combine work and family responsibilities. Once the wars were over, however, the subsidies were withdrawn, most nurseries closed down, and women were forced to leave their relatively well-paid jobs to make way for men returning from the war.

During the 1930s depression, with mass unemployment rife, finding work was all but impossible for women, let alone those with children. Those few working married women with a wage-earning husband were demonised and labelled selfish for taking up employment that could go to an unemployed man (even though men and women rarely competed for jobs in the same sector). In the cuts that were imposed, married women were denied unemployment benefits on the basis that they had no chance of finding employment – because they were married.

Women in the workforce

The situation after the second world war was very different. While from 1943-47 the number of women in paid work dropped by almost a million, by 1947 the government was already campaigning to bring back into the factories the same housewives who had only just left them, to boost essential export sectors. Those answering the call were mainly older women whose children were grown up or of school age. This was seen as a temporary expedient but was actually the beginning of the change in working mothers’ employment that has continued to the present day. A growing capitalist economy’s need for more labour in a period of full male employment, the expansion of the welfare state, women’s ability to plan and restrict pregnancies due to the wider availability of contraception, and the value of women’s additional wages to improving working-class families’ living standards, all contributed to women’s increased workforce participation at that time.

McCarthy gives a comprehensive picture, using their own words, of the reasons why working-class women with children were working outside the home in growing numbers. The ability to buy consumer goods, go on holiday or stay above the poverty line was one aspect. The women interviewed, many of whom worked in low-paid ‘menial’ jobs, also spoke about the importance of the independence that having their own wage conferred: being able to socialise outside of the isolation of the home; having a break from the drudgery of housework; feeling good about themselves. Going out to work transformed women’s aspirations and outlook.

Work became an integral aspect of their lives. They became more confident about leaving an unhappy relationship. They discovered that domestic violence was not a private problem specific to them but a social problem shared by millions of women. Working alongside other workers, they developed a collective consciousness and campaigned for issues such as domestic violence, sexual harassment and reproductive rights to be incorporated into a fighting programme of the trade unions. The transformation in their outlook, in turn, helped shape attitudes more broadly in society on the question of gender equality, discrimination and oppression.

In the last few decades, further economic and social changes have spurred labour market participation by working mothers, most importantly, the shift from manufacturing to service industries. Other factors, such as the increase in divorce (mostly initiated by women) and the rise in lone parent families, have also played a part. In the 1970s and 80s, growth in part-time work, mainly the preserve of women, was already outstripping full-time work, and this trend has continued as the capitalists seek to cut labour costs and exploit a more flexible workforce – increasing insecurity for all workers but especially women. The precarious nature of work was compounded by the mass privatisation of public services.

Labour and Tory governments have responded to capitalism’s need for flexible female labour by pushing childcare up the political agenda. But, in line with neoliberal thinking, provision has been left overwhelmingly to the for-profit private sector with the allocation of credits or vouchers to buy childcare in the privatised market. The emphasis has continued to be on women sorting out their own childcare, in a situation where provision has often been non-existent, inadequate or unaffordable. For most working-class women with children, life has been a constant struggle to juggle work and caring responsibilities, leading to stress and a large dose of guilt.

Facing the viral fallout

The coronavirus pandemic has now laid the basis for a childcare disaster. According to the Fawcett Society, up to 150,000 childcare providers could close because they are unable to operate at a profit. Closures on this level would be devastating for both the overwhelmingly female workforce in the industry and the women depending on those providers so they can work. The only solution to a crisis of this magnitude is to take the whole of the private childcare sector into public ownership, fully funded and democratically run by those employed in it and by service users. This would enable the provision of high-quality, flexible childcare, benefiting parents and children. It gives a glimpse of the enormous difference a socialist planned economy could make to the lives of working-class women, with the state also providing good quality housing, transport and other services, such as eldercare, care for the disabled, and even restaurants. It would eliminate the disadvantages of the ‘double shift’ that so many working-class women still face.

In every major recession since the second world war women have lost their jobs, although men have generally been hardest hit and the long-term process of mothers entering the workforce in ever greater numbers has not been reversed. However, the current economic crisis and impending jobs tsunami could be the first time that more women than men are made unemployed. This is due to the negative effect that their caring responsibilities could have on their jobs, and because women work in the sectors that have suffered most from lockdown – hospitality, retail, leisure, etc – and will continue to be impacted by social distancing measures. Finding alternative employment will not be easy, even if some limited areas of the economy are taking on workers. How many women with childcare responsibilities made redundant from a clothes shop on the high street are going to apply for a job as a self-employed driver working irregular shifts for a distribution company?

Mass female unemployment will not just have economic repercussions for the women concerned. It could also restrict the ability of women to leave an abusive relationship. The massive increase in women accessing domestic abuse helplines and services during the pandemic, and the rise in the number of women killed by partners, has lifted the veil on the extent of domestic violence in society. It has also highlighted the dire shortage of short-term refuge spaces and of long-term accommodation for women fleeing abuse. Unless a serious fight is waged for the government to fully fund all local services, working-class women will bear the brunt of future spending cuts, just as they did during the austerity decade.

No turning back

In terms of social attitudes regarding working mothers there is no prospect of a return to the ideology of the 1950s. Even in the recession of the early 1980s, right-wing media attacks on married women taking jobs from unemployed men held little sway. In this sense, conditions are very different from the 1930s. Working mothers are a social reality and their right to work is unlikely to be challenged in this crisis, though their ability to do so could be seriously undermined.

Women will not be prepared to passively accept a return to the home – and not only for economic reasons. It is true that, during the pandemic, some households have gained an idea of what a different ‘work-life balance’ could look like. Everyone should be able to work much shorter hours, on a decent wage, leaving more time for leisure and personal relationships. However, that would require a fundamental change in the way the economy and society are structured, removing the profit motive and implementing democratic planning on a rational basis.

Women will want to fight to keep their jobs and get back into the labour market, but they will need organisations and a leadership up to the task. One of the positive aspects of the Covid pandemic has been the influx of workers into several of the major trade unions. While this has not been an even process, it reflects a rising consciousness of the importance of unions as tools to fight for safety and in defence of working conditions, pay and jobs. Moreover, many of them have not just signed up to the union but immediately put themselves forward as safety reps and stewards. Even before Covid, women made up over half of trade union members, compared to 27% in 1975, although overall union membership was higher then. Looking at the sectors registering the biggest increases, such as teaching and social care, it is clear that women will have a crucial role in the vital task of transforming the unions into organisations capable of fighting to defend their interests and those of all workers.

Covid-19 is a watershed moment in history. It has shaken the whole of society and will awaken both a desire to fight and to search for a better way of organising our lives. Mighty battles will be necessary just to hold the line on jobs, pay, working conditions and the services working-class women especially depend on. Part of that battle will be fashioning a political vehicle for working-class people that popularises on a mass scale united, collective class struggle against not just the effects of capitalism in crisis but the system itself, and the need for public ownership and democratic socialist planning. The Covid crisis has revealed how necessary this is. It’s the only way of ending the double oppression working-class women face – and transforming the lives of all working-class people.