Of all the problems facing the British capitalist establishment in the summer of 2019, the “for now” departed Boris Johnson was only ever perceived to be the answer – or more accurately, part of an answer – to just one of them. The most pressing and urgent question of how to stop a Jeremy Corbyn-led government coming to power, with all the hopes and expectations so dangerous to the system that such a prospect being realised would have unleashed.

Under the leadership of Theresa May, the Conservatives – the oldest party in the world, and the political vehicle through which the capitalist class had traditionally preferred to exercise their rule – were in complete disarray. In the elections to the European parliament that had taken place on 23 May, the Tories had polled just one-and-a-half million votes, an 8.8% share, the first ever national election in which they had won less than 10% of the votes cast.

The fact that the European elections had taken place at all was itself evidence of how dysfunctional the party had become from the capitalists’ point of view. The government was obliged to stage the elections because it had been unable to meet the March 2019 deadline to agree a withdrawal treaty to leave the EU, following the 2016 referendum, due to the divisions on the Tory benches. The poll was won by Nigel Farage’s newly formed Brexit Party, with a 30.5% vote share, supporting a ‘no deal’ exit.

While a small minority of Britain’s capitalists favoured a ‘hard’ Brexit or even no deal, mainly among those in the more speculative, offshore-linked wing of the UK’s financial sector, this was not the position of the overwhelming majority. Recognising that they could not overturn the 2016 result, which was at bottom a mass cry of rage against the ruling establishment and the years of austerity it had delivered, they wanted to retain, at least, the closest possible alignment with the EU bosses’ club.

The European economic area is the largest single regulatory market in the global economy (in GDP terms), while reaching common positions with the EU amplifies the economic and political-diplomatic-military heft of British imperialism on the world stage. A new configuration of relations with the remaining EU27 members had become necessary after the 2016 referendum, but not a rupture. Yet all May’s efforts to deliver a deal had been repeatedly blocked in parliament and, the day after the European elections disaster, she announced her intention to resign.

The Labour Party, on the other hand, was no longer the completely safe alternative for the capitalists that it had become through Tony Blair’s transmutation of the party in the 1990s into ‘New Labour’. Even though Jeremy Corbyn, by May 2019 nearly four years into his leadership, had failed to decisively overturn the ideological and organisational legacy of Blairism and transform Labour into a democratic mass socialist workers’ party – not least in the composition of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) – the ruling class still looked on with horror at the possibility of a Corbyn victory. Workers’ expectations would have been aroused, and their confidence raised by a Corbyn-led government which, in turn, could have been pushed to go further than it originally intended in encroaching upon the capitalists’ profits and power.

Somehow, the Tory party had to be revived. Enter, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson.

One job Boris

The allegedly charismatic ‘Boris’ was presented as the only person up to the job. He had carefully cultivated a persona as ‘an election winner’, only ever having lost a contest once, in the 1997 general election in the Clwyd South constituency in North Wales. Preserving this ‘brand’ is something that explains his explosive resignation as an MP in response to the House of Commons privileges committee report – denouncing as he went “a tiny handful of people” forcing him out of parliament in a witch hunt “to take revenge for Brexit” – rather than be tarnished in a likely by-election defeat.

But back then Rishi Sunak was not alone in enthusing on Johnson’s ‘popular appeal’, as he did in a Times column headed, “The Tories are in deep peril. Only Boris Johnson can save us”. (5 June 2019) Meanwhile, putting aside Johnson’s role in the Vote Leave campaign during the 2016 EU referendum – a position he notoriously reached only after drafting two versions of a Daily Telegraph article before deciding for leave – a remainers-for-Boris group of Tory MPs was formed who hoped that he could sell a ‘soft Brexit’.

In the event, with the Tory leadership decisively won against the ‘One Nation’-backed Jeremy Hunt, Johnson agreed a withdrawal treaty with the EU that was 95% the same as that negotiated by Theresa May. The most substantial difference was the protocol to effectively leave Northern Ireland within the EU’s economic jurisdiction – insouciantly creating destabilising new contradictions for British capitalism that are still unresolved today.

Despite this, however, and the ruling establishment’s anguish at Johnson’s trashing of constitutional conventions as he lost his parliamentary majority – expelling 21 MPs from the parliamentary Conservative Party for opposing a ‘no deal’ Brexit option, and incurring a Supreme Court ruling against his five-week long prorogation of parliament – they still saw him as the ‘lesser evil’ when the December 2019 general election was called.

Which, of course, Johnson won, with the tacit backing, in varying degrees and means, by all the capitalist media without exception. Purported ‘Labour-supporting’ outlets did their bit more discreetly, in particular by feeding anti-Semitism smears against Corbyn, while the fifth-columnist Blairites within and without the PLP openly discussed how they would slow-sabotage any government that he led. The Tory vote recovered from 1.51 million in May to 13.97 million in December – which was actually only an additional 330,000 votes to that polled by Theresa May in 2017, but enough to do the job.

As the election result came in the Socialist Party wrote, in a special supplement of Socialism Today’s sister publication, The Socialist, that “the seeming strength of Johnson’s government will be shattered by coming events”. (Stand Firm for Socialist Policies to Stop the Tory Attacks, 13 December 2019) Not for us the prostration of others before Johnson as a ‘new Benjamin Disraeli’, the nineteenth century leader who recast the Tories as a ‘workers party’ – attracting support from some skilled workers in a completely different historical era of capitalist progress! – to win them office for 23 of the 31 years from 1874 to 1905. Where are those impressionistic pundits today, just three-and-a-half years later?

The reality was that, with Corbynism defeated, the glue holding the Tories together behind Boris Johnson would rapidly dissolve as the other social, economic and geopolitical challenges facing British capitalism mounted. And so it proved, with his right-wing populist playing to the narrow social base that is the Tory party membership, becoming repeatedly at odds with the wider interests of the system.

The defenestration of Liz Truss, the installation of the 2019 loser Jeremy Hunt as chancellor, and the uncontested elevation of Rishi Sunak, her defeated rival in the summer 2022 leadership race – in what was effectively a coup by the parliamentary party against the party membership – was the beginning of a concerted attempt at a ‘re-bourgeoisification’ of the Tory Party, with Johnson’s ignominious retreat from parliament just the latest twist.

Parallel process in Labour

But Johnson, to repeat, was only part of the capitalists’ answer to the problem of stopping a Corbyn-led government, and not the decisive one at that. A similar job of re-securing the Labour Party for capitalism had to be conducted too.

Even with a Labour majority in 2017 or 2019 Corbyn would effectively have been at the head of a minority government, with the most formidable pro-capitalist opposition organising against him sitting on his ‘own side’ in the PLP. Also critical to the Stop Corbyn operation were the Labour Party officialdom he inherited.

This was graphically revealed in the report on ‘The Work of the Governance and Legal Unit in Relation to Antisemitism 2014-2019’, particularly around the 2017 general election. That the evidence of the outright sabotage of the Blairite officials then was only leaked in 2020, and not made available at the time, was just one of the many mistakes made in fighting the Labour machine by the leading group of Corbyn supporters. And then there was the unchallenged caste of Blairite councillors – the ‘local face’ of Labour continuing to implement an austerity agenda – identified as a “force for sense” that could be “relied upon to rescue the party” by the New Labour guru Peter Mandelson from the outset of Corbyn’s leadership. (The Guardian, 1 January 2016)

It was the fatal flaw of the Corbyn Labour leadership that he and his leading supporters continually sought to conciliate with the representatives of capitalism within the workers’ movement rather than mobilise the mass support that his leadership had generated to remove them from any positions of influence that they held. Instead, remaining in post, they recovered so that after Corbyn’s replacement by Sir Keir Starmer in April 2020, step by methodical step they have worked to ensure that Corbynism will not rise again within the Labour framework.

Personnel and policy have been purged, up to and including Jeremy Corbyn himself being barred by Labour’s national executive committee from being a candidate at the next general election. The 2019 Labour manifesto has, in Starmer’s words, been “put to one side. The slate is wiped clean”. Speaking in May at the conference of Progressive Britain, formerly the Blairite Progress organisation, Starmer described his ‘project’ for the party as going “further and deeper than New Labour’s rewriting of Clause IV”, the move made by Tony Blair in 1995 to replace the historic 1918 commitment to “the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange” with support for the “enterprise of the market and the rigor of competition”.

“This is about rolling our sleeves up, changing our entire culture – our DNA”, Starmer intoned. (The Guardian, 13 May) “This is Clause IV on steroids”.

Could the Tories still win?

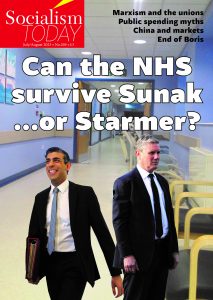

But has Starmer gone too far, putting at risk an election victory, in making his revived New Labour party almost indistinguishable from Sunak’s new Conservatives?

Even the former Tory chancellor George Osborne argued that Labour was being “too safe” when he commented on the recent decision by the shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves to delay – in the cause of ‘fiscal responsibility’ – plans for a £28 billion a year ‘green prosperity fund’. This was already a retreat from the pledges for a £250 billion green transformation fund, a publicly owned National Grid, and the nationalisation of the supply arms of the Big Six energy companies, as part of the Green Industrial Revolution promised in the 2019 manifesto. “To win an election, it’s not enough to be sort of safe and boring” said Osborne, the architect of the Con-Dem coalition’s austerity programme, the deepest cuts made in public spending since 1945. (The Guardian, 10 June) “You have to be a bit exciting, and you have to have something to offer the country about the future”.

But there does not have to be mass enthusiasm at the prospect of a Starmer-led government for the outcome of the next general election to be… a Starmer-led government. In 2005, after the Iraq war, Blair still won a 64-seat majority with just 9.55 million votes and a 35% vote share, with the Tories polling 8.34 million (32.4%) and the ‘anti-war’ Lib Dems 5.99 million (22%). The turnout was just 61.4%.

The projected national vote share that Labour polled in this year’s local elections was also 35%. The Conservatives were on 26% (with the Liberal Democrats at 20%). To win from that would require Sunak’s Tories to achieve a bigger swing for a general election than that recorded by any post-war Conservative government over an equivalent period, including Margaret Thatcher’s government after the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas war.

It suits some even on the left to exaggerate the prospect of a Tory victory, in order to avoid the conclusions the workers’ movement needs to draw. The most likely perspective is for a Starmer-led government. His revived Blairism will be operating without the cushion of the ‘great moderation’ of steady growth that characterised the world economy from the 1990s to the 2007-2008 financial crash.

The working class will need its own mass vehicle to politically represent its interests in the turbulent times ahead – and the steps to achieving that should begin now.

Contesting the vacuum

Significantly, not only was the vote of 9.55 million recorded by Blair in 2005 less in absolute terms than the 12.88 million votes Labour won under Corbyn in 2017 (and the 10.27 million in 2019). It was also less as a percentage of the total registered electorate too, 21.6% in 2005 under Blair compared to 27.9% in 2017 (and 21.8% in 2019). These latter calculations take into account population growth (the electorate increased by 2.89 million between 2005 and 2019) as well as rising abstentionism and the erosion of stable party loyalties – which were defining features of the New Labour era.

Effectively disenfranchised by the transformation of what they had seen as ‘their’ party, millions of working-class voters expressed their disenchantment by not voting at all – Labour under Blair lost 3.97 million votes from 1997 to 2005, while turnout fell by 4.1 million. Meanwhile the authoritative British Election Study recorded the proportion of the electorate reporting a strong party identification plunging to just 10% in 2005, from 45% when the survey launched in 1964.

Corbynism partially cut across this trend, with the return of at least an element of class polarisation expressing itself through the electoral arena. The biggest rise in the Tory Party’s vote since 1918 from one general election to the next – other than when facing an incumbent Labour government in 1924, 1931, 1950, and 1979 – was achieved not by Stanley Baldwin, Winston Churchill, Harold MacMillan or Margaret Thatcher but, in 2017, by Theresa May! While Corbyn increased Labour’s vote by the greatest amount ever, in absolute and percentage share terms (3.53 million, 9.6%), since 1945.

But while, with the triumph of Starmer, the vacuum of working-class political representation has returned with a vengeance – we have already seen a new angry alienation from ‘politics’ beginning – the economic, social and political conditions that produced the insurgent aspect of Corbynism have not gone away but only intensified.

What Johnson plans with his ‘for now’ departure from parliament cannot be predicted. But the age of political volatility has also shown how right-wing populism – through the Tory party or outside – can feed on the rage, bitterness and despair which is all that capitalism in decline can offer. A Starmer-led government faithfully implementing attacks on the working and middle classes in the interests of the capitalists will only add fuel to the fire.

That makes it all the more urgent, in what is now a pre-election period, to step up the fight for a union-organised workers’ list of candidates in the general election as the first step to a new mass party of the working class, and the socialist programme it would need to meet the crises ahead.