Britain is in a pre-general election period, with the likely prospect of a Keir Starmer-led government coming to power within the next twelve months, if not earlier – the first Labour government since the ‘New Labour’ administrations of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown from 1997 to 2010.

However, even those whose memories go back to the 1974-79 Labour government cannot rely on past experience as preparation for what is coming. A hundred years after the very first Labour government, victorious at the election held in December 1923, a Starmer-led government could be the one that presides over a collapse in the party’s support similar to that suffered by the social democratic PASOK party in Greece or the Parti Socialiste in France. Both were comparable parties to Labour and were electorally annihilated as they implemented vicious austerity in government after the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

Potentially, therefore, the Tory party’s ongoing implosion could be put in the shade by the crises Labour will confront in office. A Starmer-led government will face huge economic and social upheavals, be rocked by mass struggles, and doing so with a shallow social base. This poses the question of what forces will step into the vacuum created by the further fracturing of the established parties in the next period, and whether the working class, as an organised force, can play the central role.

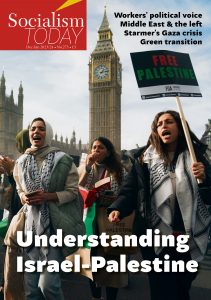

A foretaste of the pressures to come has been given by the mass movement that has erupted against the slaughter in Gaza, including the biggest pro-Palestinian demonstrations ever to take place in Britain. All those capitalist politicians backing Israel’s onslaught have been damaged, with the demonstrations leading to the sacking of the ultra-right-wing home secretary, Suella Braverman, which has further deepened the schisms in the Tory party.

Keir Starmer remains on course to become the next prime minister, but his stance on Gaza, refusing even to call for a ceasefire, has deepened his unpopularity and opened new splits within Labour. However, the parliamentary rebellion on November 15 over the Scottish National Party’s (SNP) ceasefire resolution also demonstrated how marginalised the Labour left now is under Starmer’s iron grip. Only just over a quarter of the Parliamentary Labour Party rebelled even on this issue and, of those, only 23 were Labour members of the Socialist Campaign Group of MPs, the rest acting primarily to try and shore up their vote given the character of their constituencies.

Nonetheless, this, and the resignations of over 50 Labour councillors, give a glimpse of the divisions that can develop in government – even within what has now been re-established as a capitalist New Labour party – under the impact of events. Not least will be the consequences of the weakness of British capitalism, against a background of a crisis-ridden global system. Ultimately, this is what lies at the root of the Tories multiple crises, and Labour will face a worse situation.

Shadow chancellor’s Rachel Reeves endless speeches about fiscal responsibility reflect the real constraints faced by capitalist governments in Britain. The very best that Starmer can hope to inherit economically is a continuation of the current stagnation, with a national debt of over 100% of GDP for the first time since 1961; public sector workers who have suffered over a decade of real-term pay cuts and expect Labour to change the situation; at least 26 councils facing bankruptcy and many more desperate for a bail out; and an NHS, along with other public services, at or even beyond breaking point.

Election prospects

It isn’t possible to predict now whether Britain, or the world economy, will already be in recession at the time of Starmer becoming prime minister, or whether that will lie ahead. We can predict, however, that he will become prime minister. The Tories got 26% of the vote in the 2023 local elections and opinion polls since have consistently put them at that level or even lower. To win the next general election Sunak would need a bigger swing than any post-war Tory government has achieved, including Thatcher’s re-election in 1983 in the immediate aftermath of the Falklands war. There is no prospect of that taking place.

It is possible that Starmer’s Labour will win a big ‘1997-style’ majority. However, even if that is so in the number of seats, it will be very different in enthusiasm and probably in the absolute number of votes. In 1997 there was a 71% turnout, and Labour received 13.5 million votes. By the time of New Labour’s last election victory, in 2005, turnout had fallen to 61% and Labour’s vote to 9.5 million. Since then, Labour has only got over ten million votes twice, in 2017 and 2019 under Corbyn’s leadership. These elections – particularly 2017 – were exceptional in the modern era.

In 2017, 82.3% of voters voted either Tory or Labour. It was not only Labour that had an increase in votes – the Tories’ 42.3% was their highest percentage since 1987! Prior to this the proportion of the electorate who voted for the two main parties had been in steady decline, with just 65.1% voting for them in 2010, for example. The reason for the temporary reversal in that trend is clear; it was a partial return to class politics, even with the limitations of ‘Corbynism’. On the one hand wide layers of the working class and young people voted Labour because they hoped for a government that would stand in their interests; while the capitalist class did all it could to mobilise the Tory vote as the means to stop Corbyn being elected.

Now, with a return to ‘New Labour’ and no fundamental class differences between the major parties, we have again increasing fragmentation, protest votes, and lower turnouts. For example, Labour won both the Mid-Beds and Tamworth by-elections on October 19, but its votes flatlined compared to the supposedly ‘dire’ 2019 result; it was only the collapse in the Tory vote that enabled it to claim victory. It is perfectly possible that Labour will fail to break the ten million barrier again in the next general election, yet still win a sizeable majority as a result of a low turnout and small Tory vote.

This was true before the Israeli onslaught on Gaza, but Starmer’s slavish alignment with US imperialism has enormously added to the anger with him. In the 2019 general election 71% of Muslim voters supported Labour. Polls vary on what that has fallen to, but it is clear the drop is substantial. The growing anger and distrust in Starmer demonstrates the space that exists to the left of Labour. If the absence of authoritative forces from the workers’ movement stepping into that vacuum continues, however, it will lead to more people staying at home, and an increase in votes for other parties including the Greens. Obviously, though, it will not do anything to rescue the Tories. Nonetheless, it is not excluded that it could deprive Starmer of a majority, forcing Labour to rule as a minority government or in coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

Different character of this Labour government

The economic backdrop is central to why there is no prospect of a Starmer-led government achieving the relative stability of New Labour’s early years under Blair. In 1997 the economy grew by 4.9%, the fifth successive year of relatively strong growth. The national debt was 40% of GDP. New Labour had promised to maintain the Tories spending plans and did so for their first three years in office, but beyond that was able to increase public spending, albeit with privatisation and the embedding of private capital into public services. Despite Starmer’s determined refusal to promise anything, there will still be an expectation that his government will substantially improve the current dire situation, but – given his total acceptance of the dictates of the market – he will at best be able to marginally reallocate the pain.

It is not only the economy, however, that could push a Labour-led government into crisis quite quickly. It will also lack authority among the working class from day one. Historically, British capitalism has relied on Labour governments, when Labour was a ‘bourgeois workers party’, to introduce measures which the Tories could not. In 1974, for example, the Labour government, in power during a period of economic crisis, was able to get away with implementing wage restraint for some time before mass struggle erupted against it. Labour was then a bourgeois or ‘capitalist workers party’, with a working-class base which via its democratic structures could exert pressure on its capitalist leadership. This was a Labour government elected after the Tory prime minister Ted Heath had gone into the February election asking, ‘who runs the country – us or the miners?’ The vote for Labour was a conscious vote by workers for a party they saw as ‘theirs’, which had implemented real reforms in the recent past. For a period, trade union leaders were therefore able to hold back struggle on the basis the government had to be ‘given a chance’. A Starmer-led government will not have one-tenth of the authority with the working class that Labour had in the 1970s.

Nor will the situation be comparable to 1997. Labour by then had been transformed into an unalloyed capitalist party. Its democratic structures, via which the trade unions could exert pressure on the leadership, had been largely destroyed. None of that is fundamentally different today, but the world has changed dramatically. This was after the collapse of the Stalinist regimes of Russia and Eastern Europe – which were not models of genuine socialism but a grotesque caricature of it – in a period in which capitalism was widely seen as the only viable option, and support for socialism was marginalised. Illusions existed in Blair’s alleged ‘third way’, for example, which claimed to combine neo-liberal economics with ‘progressive’ social policies. The trade union movement was in retreat. As a result, there were no national strikes against the Labour government until the firefighters strike in 2002.

In contrast, today most of the generation that have grown up in the years since the Great Recession would consider themselves left-wing. Their consciousness has been shaped by their experience of capitalism. Even today, those born in the late 1980s are earning an average of 8% less at 30 years-old than the generation before them. No wonder one recent YouGov poll estimated that only 12% of 25-49 year-olds intend to vote Conservative at the next general election, whereas 67% consider themselves to be ‘socialist’. The popular support for Corbyn, especially among the young, was a reflection of the search for an alternative to capitalism.

At the same time the working class, far from being in retreat, has begun to recover its fighting capacity. Last year saw the highest level of strike action for over three decades, since the collapse of Stalinism. All of these ingredients, combined with the dire state of the British economy, mean that Starmer will have an infinitely rougher ride than Blair in his first term.

Workers’ political representation

This does not mean that in the early days of a Starmer-led government many will not desperately want to believe that Labour is going to markedly improve their lives or at least be ‘better than the other lot’. But in general, any hopes in an incoming Labour-led government will be far shallower than any previous Labour administration taking over after a period of Tory rule. And shattered by the reality of Starmer in power, the issue of how the working class can be politically represented will be ever more firmly placed on the agenda.

There have, however, been no significant moves towards a new party to date, and it is most likely that there will not be before the general election. No trade union leaders have taken steps in that direction. At the Unite rules conference in July the general secretary Sharon Graham, unfortunately, successfully argued to maintain the union’s affiliation to Labour at this stage. In the non-affiliated unions, at the RMT transport workers’ AGM there was unanimous support for the motion Socialist Party members had initiated to support Jeremy Corbyn if he stood as an independent. However, the general secretary Mick Lynch used his authority to argue strongly that Labour was the ‘only show in town’ in the forthcoming election. While there is no enthusiasm for Starmer’s New Labour among trade unionists, union leaders can still utilise the deep, visceral desire to get rid of the Tories in order to justify a failure to act on this question.

Nonetheless, the possibility exists of the RMT and BFAWU bakers’ union backing independent workers’ candidates at the general election, including under the banner of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC). It is right to campaign still for the idea of the broadest possible workers’ list at the general election and it is possible, as the anti-war movement is demonstrating, that events can push the issue forward. The likelihood of Corbyn declaring he is standing as an independent, alongside some other left former or suspended MPs like Emma Dent Coad, will also have an effect.

So campaigning on this issue, including mounting some challenge in elections, is vital preparation for what is coming under the next government. It is possible, although not certain, that mass struggles and strikes will develop before the issue of a new party to the left of Labour is posed. However, it can be said with certainty that union funding of Labour, and the need for the unions to instead found a new party, will become a sharp debate in the trade union movement.

Danger of reaction

Arguments to support Labour as the ‘lesser evil’ will not cease after the general election, however. The spectre of Suella Braverman, or someone like her, becoming prime minister if ‘the unions don’t back Labour’, will be raised. In fact, of course, as discontent with New Labour Mark II grows the only way to prevent the right populists being the main force to take advantage of that will be the development of a mass anti-racist workers’ party fighting Labour from the left.

Reform UK currently have 8% in opinion polls, but Britain has not yet seen the development of the kind of far-right and right-populist parties that have grown in many European countries. Mostly this is because the increasingly ‘populist’ Tory right wing are occupying that space. As a hated party of government, the Tories’ attempts to whip up racism in order to gain a few votes have not worked, at least in gaining them any votes! Nonetheless, there has been a foretaste of what they or their ilk could whip up under a Starmer-led government in some of the anti-refugee protests that have taken place.

The Tory party is the historic party of Britain’s capitalist class, but it is no longer a reliable tool for them. Rishi Sunak is a more ‘reliable’ representative of the general interests of British capitalism than Boris Johnson or Liz Truss, but he is unable to consistently act on its behalf given the right-populist character of the parliamentary Tory Party, reflecting the narrow social base of the party membership.

Beyond the general election it is clear that the Tory civil war will accelerate. The right populists aim to sweep the board, but the capitalist class will not lightly give up on a potential political vehicle for their rule. David Cameron’s appointment as foreign secretary is only secondarily about trying to save the Tories from oblivion in the general election. It is more about the ‘establishment’ Tories campaign to try and wrest back control of the party beyond the election. It is not possible to say now what the outcome of those battles will be. It is not even possible to say who the depleted band of Tory MPs conducting them will be, given the number who will be booted out in the general election. A reconfiguration of British politics will be on the agenda, however. Possibilities include a new more powerful right-populist party emerging outside of the Tories, or bigger sections of ‘traditional Tories’ giving up on their party and leaving it to the ‘swivel-eyed loons’.

Capitalism offers no way forward for humanity, and the working class will be forced by that reality onto the road of struggle. Mass support for socialist ideas will develop. That process is still in its beginnings, but in Britain – along with other countries – it is of huge importance that the working class has begun to feel its collective power. At the same time there is a searching for an alternative to this rotten system among millions of young people particularly. All this is preparing the ground for the much greater steps forward in building the forces of socialism that will be possible in the coming period.