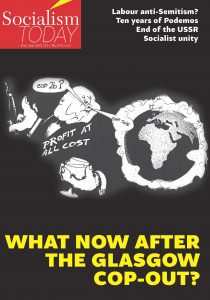

The conclusions to be drawn from the Glasgow-hosted twenty-sixth Conference of the Parties UN climate summit (COP26) that closed on November 13 should be clear for climate campaigners. They are certainly not new.

Once again representatives of the world’s most powerful capitalist nation states – and the formally ‘non-market economies’ in World Trade Organisation (WTO) terms also present – were unable to overcome their competing economic and political interests to avert the prospect of future catastrophic climate change.

Nicholas Stern, author of the authoritative 2006 UK government commissioned report, at the time famously called climate change the result of “the greatest market failure the world has seen” – a failure, in other words, of capitalism. Nothing that transpired in Glasgow contradicts that now well-established assessment.

Once again COP26 has also confirmed – in the negative unfortunately – that only mass movements of those with no stake in capitalism could compel the political representatives of the ruling capitalist classes to act against their different national interests (and geopolitical concerns); and accede to the system-threatening measures that are necessary to combat climate change.

To build such sufficiently powerful movements requires, above all, a struggle to mobilise the working class and its mass trade union and community and social movement organisations for the battle to save the planet.

Despite the failure of the talks, however, Glasgow should not be a cause for unremitting pessimism.

The environmental crisis is now unavoidably integral to the economic, social and political crises that will confront the capitalist system in the years ahead. Boris Johnson’s one perceptive moment at the talks was when he warned the assembled leaders that the developing climate crisis risks a “backlash from the people [that] will be immense and it will be long-lasting” (10 November).

Climate change and its escalating consequences will both generate and feed into the mass movements that will come. In the process it will certainly not be impossible to compel different capitalist classes across the globe to enact climate measures – in their national terrains and internationally – if they see their rule in jeopardy; even if only in partial and temporary (and thereby potentially reversible) retreats.

But it is this constant tension between the interests of the planet and those of capitalism which is also the reason why the potential threat to the ruling classes posed by mass opposition to climate change needs to be followed through; the most important conclusion not just from COP26 but the almost 30 years of failed climate talks that preceded it.

It is not the working class and the poor, nor the middle classes either, who are responsible for the possibility of runaway climate change. It has been under the capitalists’ stewardship of society that the planet has been brought to the perilous position it is in today.

If mass movements in response to the climate crisis, and other crises, can be built that seriously challenge the capitalists’ rule – the only way the ruling classes will be forced to act – why should they stop there? The struggle to save the planet is not separate to but part of the struggle to take power out of the hands of the capitalists and begin a new collaboration of peoples in a socialist world.

Glasgow failure

The capitalists’ establishment media had been prepped to hail the Glasgow summit for ‘keeping 1.5C alive’, a reference to the 2015 Paris climate talks which had formally agreed to hold global temperature rises to “well below two degrees Celsius” (2C) above pre-industrial levels – still catastrophically high – but to “pursue efforts” to limit the increase to 1.5C.

The Guardian’s environment correspondent Fiona Harvey duly portrayed the rebuttal of some delegates’ attempts to argue that focusing on 1.5C was “reopening the Paris agreement”, as a victory. “The argument at Glasgow was firmly won in favour of 1.5C”, she wrote, “in itself an achievement for the UK hosts”. (15 November) But generally even the most ideologically pro-capitalist journalists struggled with the brief.

The Economist magazine was realistically brutal. “The painful reality suffusing the conference”, they reported, “was that the world is failing to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, despite promising to do so in the Paris agreement of 2015”. (20 November)

The pledges on greenhouse gas emissions made in 2015, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), would have led to a likely 2.7C warming by 2100. The Glasgow pledges reduced that by 0.3C, to 2.4C.

Another metric is to quantify the greenhouse gas emissions reductions, in addition to current commitments, that need to be achieved to get to no more than a 1.5C rise. The Climate Action Tracker research group, studying 32 countries accountable for over 80% of global emissions, estimated that before the COP26 talks, a further 23 billion to 27 billion tonnes of emissions needed to be avoided by 2030 to ‘keep 1.5C alive’.

The new NDCs presented in the run-up to Glasgow reduced that by just four billion, with a further two billion agreed at the summit in pledges on methane, coal, electric vehicles and forestry. So well over 70% of the emissions reductions needed by 2030 on top of existing targets are still to be pledged, never mind implemented. The world’s capitalist leaders are irrefutably not delivering.

No alternative routes

Even the (minimal) pledges on methane, forest protections and others were not the result of consensus agreements between all the 197 countries represented in Glasgow. Instead, in a departure from previous UN climate talks, they came from what The Economist described as “assorted coalitions of the willing” of different nation states, regional blocs, and industry or sector alliances, reflecting their own particular interests.

This included the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) of banks, insurers, asset managers and asset owners, holding a combined $130 trillion of assets, who pledged to try and cut the emissions from their lending and investments to net zero by 2050.

As an Economist editorial commented, however, “pledges like GFANZ are good as far as they go” but private financial firms exist to “maximise risk-adjusted profits for their clients and owners”. (6 November) “If you can brush off the stigma, it can be profitable to hold assets that can legally generate untaxed externalities [an unearned benefit from outside the market] – in this case pollution”.

The Economist points to the problem in order to make its case for a widely enforced carbon emissions price or tax, so that “the job of the financial system would then be to amplify the signal sent by the price of carbon”, creating a market mechanism to draw capital away from fossil fuels. But, whereas a nation state can enforce a tax or a regulation to effectively place a value on nature within its jurisdiction (or at least attempt to), who would do so internationally?

After all, the first ‘coalition of the willing’ – which actually did re-shape global energy markets – was the 2003 US-led Iraq invasion force (with the UK under Tony Blair a mini-me sidekick), intervening to protect the economic interests of western imperialism, especially at that stage the oil industry ironically, and to re-assert the prestige of the USA on the world stage after the 9/11 attacks. Is there really anything in that model for the task of combating climate change?

Some climate campaigners, however, welcomed the idea of such ‘plurilateral’ action, after the failure of Glasgow’s multilateralism.

The former Guardian environment editor John Vidal, urged “governments” that “want progress” – representing who, which class? – to “take the gloves off, treat the few countries (sic) that are preventing climate action as criminals, and reward those that do act with trade deals, contracts, investment and aid”. (15 November)

What is this really but a greenwash of the inevitable energy and technology trade wars – between the US and China, for example, despite their joint Glasgow declaration – clashes over environmental refugees etc, and the general heightened tensions between the world’s major powers that will develop if capitalism is not overturned and as the climate crisis unfolds? Argued with the best of intentions, no doubt, but a cry of hopeless despair. The capitalists shall remain in power and the system shall remain in place.

Other climate campaigners though, like the 350.org campaign group founder Bill McKibben and the Guardian columnist George Monbiot, correctly drew the conclusion from Glasgow of the need, in Monbiot’s words, to “build the greatest mass movement in history”. (15 November)

But the questions still remain: how can movements be built that are sufficiently powerful, nationally and internationally, and what should their aims be?

Lessons of previous movements

There has been debate amongst climate campaigners about the levels of support that are needed for mass movements to succeed. George Monbiot has previously argued that “a maximum of 3.5% of the population needs to mobilise… when a committed and vocal 3.5% unites behind the demand for a new system, the social avalanche that follows become irresistible”. (The Guardian, 15 April 2019)

But instead of what can be a somewhat academic argument, a better approach would be to study real mass movements that have taken place in recent history, such as the anti-poll tax rebellion that brought down Margaret Thatcher in 1990, or the lessons of the anti-war movement in 2002-03.

The battle against the poll tax in the late 1980s and early 1990s unquestionably had mass support. Just the magistrates’ courts of England and Wales saw 25 million cases brought before them for non-payment of the tax in the period between April 1990 and September 1993, according to Home Office figures collated by the House of Commons Library for the former Militant Labour MP, Dave Nellist.

Even then, however, the victory that was achieved was not a forgone conclusion. The state powers to enforce the tax were formidable. If there had been no organised movement against the tax it may well have survived, with some modifications such as expanded rebates.

But a campaign with sufficient weight to shape events was organised, by Militant, the predecessor of the Socialist Party. We were able to provide the politics, strategy, tactics and organisation – beginning from a debate at a Scottish conference of Militant in April 1988 – to weld the mass discontent with the tax into a coherent movement. Two and a half years later Thatcher fell and the abolition of the poll tax was announced in March 1991.

We were able to accomplish this, with just 5,700 members across Britain (as recorded at our national congress in November 1989), because we had a clear programme and perspective for socialism, which was far from being an obstacle to building and leading a mass movement but a vital necessary ingredient.

How much more so is that the case when it is the future of the planet that is at stake? When the task of re-organising the economy on a net zero carbon basis, for example, has the potential to generate divisions around sectional interests within the working class?

The anti-poll tax campaign had the ‘advantage’ that Thatcher created the basis for unity by taking on the working class as a whole around a single, easily identifiable issue. How much more important will it be that the climate movement has a broad socialist programme to bring workers together nationally and internationally, alongside the development of independent working class parties to struggle and discuss collectively?

Only in this way will different sections be able to move beyond their own particular concerns and develop a wider consciousness of their class interests and the need for governmental power and a new society.

The broader political impact of the anti-poll tax movement going into the 1990s was muted by the objective fact of the ideological triumph of capitalism after the collapse of Stalinism in Eastern Europe and the USSR, the thirtieth anniversary of which we cover in Clare Doyle’s article in this issue, and the impact of this on workers’ consciousness and their organisations. (See also In Defence Of Our Great Anti-Poll Tax Victory, in Socialism Today No.241, September 2020)

But the era ahead will be completely different to the 1990s and the rich lessons of the anti-poll tax movement will be revisited in the struggles to come.

No separate climate politics

The movement against the war on Iraq also generated mass support, as the countdown to the invasion unfolded from 2002 into early 2003. A contemporary ICM poll recorded that at least one person from 1.25 million households participated in the February 15 demonstration in 2003. (The Guardian, 18 February 2003)

Motherwell members of the ASLEF train drivers’ union refused to deliver munitions to NATO’s largest weapons base in Europe at Glen Douglas, the first such incident since Britain’s war of intervention against the 1917 Russian revolution. The British ruling class were shaken but, on 19 March, the invasion began.

The stakes were high for both the New Labour prime minister Tony Blair and the capitalist ruling class that he represented. Having built up an invasion force, to have then retreated with Saddam Hussein still in power in Iraq would have been an enormous blow to the authority and prestige of US imperialism and its British junior partner. Blair’s rule, and the capitalists’ interests, had to be put at a greater risk from a movement at home than they would have been by not going ahead with the war.

But the leadership of the anti-war movement, including left-wing Labour MPs and trade union leaders and the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP), had not developed the movement from one of protests and mass demonstrations – there were six between September 2002 and March 2004 – into a mass, working class political challenger to New Labour. (The SWP’s role in stymieing the promise of the Socialist Alliance in this period is explored in two articles from the time that we reprint in this issue) Such mistakes must not be made again.

In this context the response of the trade union leaders to COP26 was far from what is required. An appeal to the summit asking it not to “agree significant reforms… without listening to workers” was signed by 14 union general secretaries representing 2.3 million workers.

It did rightly say that “workers’ organisations must be at the heart of tackling the climate crisis and building a world fit for the future”. But one signatory, for example, was Matt Wrack, whose Fire Brigades Union has a policy, going back to 2012, for the nationalisation of the banks, so that “a publically owned banking service, democratically and accountably managed… could play a central role in building a sustainable economy, investing in transport, green industries” and eco-friendly housing. So why wasn’t that promoted, to answer the hypocritical summit greenwashing of the GFANZ billionaire bankers?

Another signatory was the RMT transport workers’ union general secretary Mick Lynch. But the union also has annual conference (AGM) policy, from 2018, for nationalisation of the banks. Its constitution, moreover, commits the union to “work for the supersession of the capitalist system by a socialistic order of society”.

When is the time to raise such ideas, if not when the world’s capitalist leaders are gathering in Britain to discuss the fate of the planet? There may have been fewer signatories – the Blairite general secretaries of the UNISON public services union and the shopworkers’ union USDAW didn’t sign even the moderately-worded appeal – but it would have given a clearer lead to the millions of workers and young people looking on with alarm at the summit’s failure.

Meanwhile Tony Blair’s New Labour is being revived, with Keir Starmer jettisoning Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell’s Green Industrial Revolution policies, including public ownership of the energy and water sectors.

“We are now the pro-business party”, the shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves told a Sunday Times interviewer, who commented on the changes since 2019 when his questions for John McDonnell “revolved around Labour’s plans to nationalise the rail and water industries. ‘We’re definitely not going to talk about that’, Reeves said, laughing”. (21 November) When will it be time – while New Labour chuckles as the world burns – for the left union leaders to take the lead in the steps necessary to create a party to represent the working class?

There are no separate politics for the climate crisis. Only that the tasks after the Glasgow cop-out are even more urgent than they were before.