The recent national congress of the Socialist Party, held from 14-16 May, began with a discussion looking at global developments and perspectives for national conflict, economic crises, and the struggle for socialism. Here we reproduce the introduction to the discussion, made by the Socialist Party general secretary, HANNAH SELL.

Today we are assessing the world that is emerging on the other side of the Covid pandemic. It threw all aspects of society into flux. It has created enormous economic uncertainty and increased tensions between nation states, different sections of ruling elites and, above all, between classes.

Of course even now the pandemic is not over. Part of the reason that the Chinese regime has set its lowest growth rate target in three decades is that it is struggling to deal with a huge surge in Omicron. There are currently 290 million people in harsh total lockdowns, which are increasingly ineffective and unpopular. There are numerous reports of people in Shanghai protesting because they have been locked down without food for days at a time. Nonetheless, on a global basis – while Covid is still an ongoing cause of stress in people’s lives, and a disruptor of the economy – it is increasingly becoming seen as an endemic disease: one more problem that society has to deal with.

Plunge in living standards triggers revolt

There was never any prospect of the post-pandemic world being one of sunny economic uplands, rising prosperity and capitalist stability. But instead we’ve seen an escalation of the crises of global capitalism, with all existing trends intensified. The first months of 2022 have seen a dramatic, global, fall in the real living standards of the working class and poor. Food prices are at the highest levels ever recorded. Billions of people, especially in the neo-colonial world, face starvation.

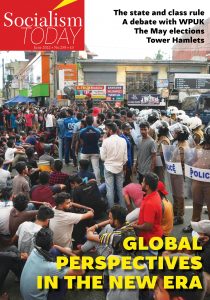

This nightmare will lead to revolts developing in different countries. Just as increasing food prices were an important trigger for the revolutionary wave which swept the Middle East and North Africa in 2011, the current crisis will inevitably lead to new uprisings, as we are already seeing in Sri Lanka. Historically, Sri Lanka has had higher living standards than much of South Asia. Now there are huge shortages of everything. Faced with this situation the whole society has gone into revolt against all existing politicians. The country has been shaken by the biggest general strike since 1980. The movement has so far forced the resignation of one prime minister and as yet shows no sign of abating. It is a foretaste of what is to come in other countries and poses sharply the central issue of the coming period – this enormously heroic movement began without any clearly defined leadership.

The forces of the Committee for a Workers International (CWI) in Sri Lanka, organised in the United Socialist Party, are able to have an important influence. But they are not yet strong enough to have a decisive effect. What is needed is an established determined leadership, fighting for a workers’ government with a clear programme – starting with non-payment of all debts, nationalisation of the banks and capital controls, but not leaving it at that. Also required is nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy, the implementation of an emergency plan to meet people’s needs, and an appeal to the working class of other countries for solidarity. That programme is not unique to Sri Lanka but will apply in numerous countries.

The world situation poses ever more urgently the need to build revolutionary parties capable of successfully leading a struggle to overthrow this rotten system and establishing a new democratic socialist order. That does not only apply to the neo-colonial world. The working-class of the economically-developed capitalist countries also faces what gets called, in a complete understatement, a ‘cost of living squeeze’. In Britain we’re facing the biggest fall in living standards since 1956 and the same tale can be told in the US and across the EU.

Just as we’re seeing the first beginnings of a new wave of industrial militancy in Britain, the same is true in other countries. There has been a marked increase in strikes and strike threats over pay in Germany, the biggest economy in Europe. And in the US, from an even lower base than here, we are nonetheless seeing very important unionisation struggles, like the successful ballot for recognition in Amazon Staten Island. Last year there was a 50% increase in the number of ballots for union recognition in the US.

The multipolar world

The urgent need to build parties with clear socialist programmes is also posed by the other side of world developments. It is absolutely clear that, as we predicted, the post-pandemic world is one with a qualitatively increased level of tension between nation states, as is currently being played out on the battlefields of Ukraine.

Of course, war isn’t new. And we understand the sometimes angry reaction of refugees from wars in Asia and Africa, when they see the wall-to-wall coverage by the capitalist media in Britain of the nightmare in Ukraine, while, to give one of many examples, the 10,000 children who’ve died at the hands of Saudi-backed and US-armed forces in Yemen are never mentioned. Nonetheless, the horrific invasion of Ukraine does mark a major turning point in world relations. It has a large element of a proxy war between Western imperialism, the US in particular, and Putin’s gangster-capitalist regime.

The very fact it is taking place is itself an indication of the decline of US imperialism. While it is still the world’s strongest power events are not in any sense under its control. There was a very brief period, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, where there was a ‘unipolar world’ with US imperialism able to a considerable extent to ‘call the shots’, while world markets were increasingly opened up to unrestrained access for Western, particularly US capitalism. That short period has long since been shattered by events, including the overreach of the Iraq war, and then the 2007-08 financial crisis.

The decline of US imperialism is combined with China rising as the second global power. That does not mean China is about to overtake the US. While its military spending has accelerated enormously, for example, to second in the world, it is still less than a third of that of the US.

China itself, with its peculiar form of state capitalism, is riven by contradictions, which will come to the fore at a certain stage. It has an enormously wealthy capitalist class, its 626 billionaires second only to the US. At the same time the ‘Communist Party’ controlled Chinese state is not simply an agent for the Chinese capitalist class. It learnt lessons from the collapse of Stalinism in the Soviet Union, and was determined to keep control while fostering the development of a capitalist class. Today it still has a large degree of autonomy in steering the development of capitalism in a way that best preserves its own power.

Over the last year we’ve had a glimpse of the huge tensions inherent in that situation, as Chinese President Xi has acted – and so far got away with – curbing the power of different sections of the capitalist class. However, particularly on the basis of slowing economic growth, more open conflict is likely at a certain stage. And as the Chinese state attempts to mobilise support, it could rely even more on whipping up nationalism, including the possibility of escalating threats against Taiwan.

Both sides are more than dimly aware that the tension at the top of Chinese society could spark revolution from below. And that the biggest danger to both their interests will be when the Chinese working class – potentially the most powerful in the world – moves into action. However, knowing that will not mean that they can indefinitely paper over the cracks.

But while China’s rise will face all kind of complications, it is clear that the US is no longer all-powerful. Putin’s regime felt confident to invade Ukraine, knowing that US imperialism and the NATO powers were powerless to prevent it, and that China, while formally ‘balancing’ on the issue, would not be carrying out sanctions against Russia. As a result the multipolar world we have described is now expressed militarily in East Ukraine.

Puny Russian imperialism

That is not to suggest that this brutal war is a sign of the strength of Russian imperialism. On the contrary, it is a huge miscalculation by Putin which is likely at a certain stage to finish him off. The Russian regime did not foresee the ferocious Ukrainian resistance they have faced. It is estimated that 15,000 Russian soldiers have been killed so far, more than the whole decade of Soviet Union intervention in Afghanistan. Even if those figures are not accurate it is very clear that the invasion has so far gone badly for Putin.

The Russian army has been forced to change tactics, with its retreat from the fantasy of taking Kyiv, and is now engaged in a brutal metre-by-metre slog to gain territory in the east, with all the horrific accompanying bombing of civilians that we have seen on our TV screens. Even the Economist magazine has quoted the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky about the state of the Russian army, when he said, “the army is a copy of society and suffers from all its diseases, usually at a higher temperature”. Russia is in reality a very weak and primitive economy – around the size of Belgium and the Netherlands combined – and completely dominated by the production of oil, gas and raw materials.

The Stalinist Soviet Union was a brutal bureaucratic dictatorship which bore no resemblance to genuine socialism. Nonetheless, it was based on a distorted form of a planned economy, and for a whole historical period presided over dramatic economic growth. However, that reached its limits, as the gargantuan bureaucracy at the top became an absolute fetter; unable to develop a modern economy. But its collapse, and the restoration of capitalism, was a disaster.

From 1991 to 1994 average male life expectancy dropped by five years as a result of a catastrophic fall in living standards for the majority. Meanwhile a few oligarchs in Russia, Ukraine and every part of what had been the Soviet Union looted the state’s resources. Putin and his coterie, utterly incapable of developing the economy, were the gangsters who clawed their way to the top (see How Russia’s Gangster Capitalists Seized Power, by Peter Taaffe, in Socialism Today No.257). Russia went from being at the centre of an economy half the size of the US to being one thirteenth of the size.

Despite Russia’s huge military spending its extreme dysfunctionality is being revealed on the battle field. While we cannot get a completely accurate picture through the ‘fog of war’, it is clear that high death rates have been combined with cases of soldiers refusing to fight, vehicles running out of fuel, tanks sinking in the mud because they have the wrong tyres, and all the rest of it. However, having started, Putin is desperate to achieve something that could be painted as a victory. Russian troops are now focusing on the East of Ukraine but any progress is extremely slow.

Western imperialism’s change in tactics

Of course it is not only Putin that has changed tactics after his forces have been tested on the battle field – so have the Western imperialist powers. We stand for the right of all the peoples of the region to genuine self-determination. The only time they had a real chance to take steps in that direction was in the period after the 1917 Russian revolution, before the rise of Stalinism. Even Putin had to acknowledge that. His main speech in February justifying the invasion consisted of an attack on Lenin, leader of the Russian revolution, for his intransigent support for the national rights of all oppressed peoples, not least the Ukrainians. But just as the rights of the people of Crimea or Donetsk are, in reality, so much loose change for Putin, neither is US imperialism – nor Johnson, among the most determined to wrap himself in the Ukrainian flag – motivated by concern for the peoples of Ukraine.

Having been surprised by Russia’s military weakness, the Western powers see an opportunity to weaken and undermine the Russian regime by providing weaponry for the Ukrainians. So in reality, neither side is seeking a peace deal at this stage, and this war could grind on for some time. At some point a stalemate is likely to lead to negotiations along a fragile ceasefire line, but where that line would be drawn is currently unknowable, and it would not be real peace but rather a continuation of a ‘frozen’ war at a lower level. Nor will this be the only war; we have entered an age of increased military conflict.

Horrifyingly, the war is being accompanied by increased talk of the nuclear threat. That has included speculation this week from Avril Haines, the US director of national intelligence, that, if facing defeat, it could not be ruled out that Putin would use a tactical nuclear weapon. Undoubtedly, an element in her motivation for raising that was a warning to Johnson and the other ‘ultras’ that at a certain stage it could make sense for NATO to negotiate a deal, possibly including accepting Russia gaining territory. The more far-sighted representatives of US imperialism are worried not only about what Putin might do if facing defeat, but also that, if he was forced out, it is unlikely he would be replaced by a pliant pro-Western regime, but rather by a chaotic and much worse situation for Western capitalism.

Putin has, of course, repeatedly indulged in nuclear posturing as a means to hold Western forces back from escalating their intervention. While such posturing has a clear logic from his point of a view, using a nuclear weapon – even Russia’s smallest which are about a fifteenth of the size of the Hiroshima bomb – would have disastrous consequences, not only for those it killed and injured, but also for the Putin regime. It would be opposed by China which Putin is increasingly economically dependent on. More importantly, it would lead to mass anti-war movements that would be likely to quickly end Putin’s rule. Nonetheless, while nuclear war is not on the agenda, Putin ordering preparations for a so-called ‘tactical’ nuclear strike can’t be totally ruled out, given the highly dysfunctional character of the Putin regime which lacks many of the checks and balances of more ‘normal’ capitalist regimes.

However, the current absence of many such checks doesn’t mean Putin and the small clique around him will indefinitely remain – as currently appears to be the case – able to take whatever decisions they like on behalf of the Russian state. At some stage we could see a ‘palace coup’, as a section of the state moves to remove Putin because he is so badly damaging the interests of the capitalist class in Russia. Any move from empty to real threats on the nuclear question could be a trigger for such a coup. But aside from that, at a certain stage the Putin regime will come under threat because of the growing unpopularity of the war and its consequences. The Russian economy is predicted to contract by 10% this year, while body bags are starting to pile up.

Right now polls show there is still majority support for the war in Russia. This is no surprise. It is usually true that capitalist classes can successfully whip up support in the early stages of a war. Today we remember the huge demonstrations and mass opposition here to the Iraq war before it began. However, in fact, once it had started there was initially majority support for the war, and a widespread mood that we had to back ‘our’ soldiers. And to give a very famous example from the start of the first world war, at the beginning the socialist internationalists from all countries – including the Bolsheviks from Russia – fitted into two stage coaches, so small were their numbers. Yet two years later the Bolsheviks led a mass movement which overthrew capitalism in Russia.

Particularly given the scale of repression they faced, the size of the anti-war demos at the time of the invasion indicates that there is already significant opposition to the war in Russia. Even recent opinion polls, particularly those that ask less direct questions which people feel more able to answer honestly without fear of reprisals, show, for example, that as many Russians predominant emotions around the invasion are fear and worry as are national pride. It could indicate growing disquiet that five regional leaders in Russia resigned this week. While timescales are uncertain, it is clear this war will ultimately weaken the Putin regime, and is preparing the ground for gigantic struggles convulsing Russian society.

NATO’s divisions and unpopular leaders

However, the US and the NATO powers will also be weakened by this conflict. Clearly, there is a concerted attempt to use the war to strengthen the Western imperialist powers. The role of NATO has been reasserted. Less than a year ago the US didn’t even bother to inform its NATO allies before its headlong retreat from Afghanistan. At the same time there is an attempt to increase the social base of the Western imperialist powers, as they falsely pose as the defenders of democracy.

Will either attempt work? Momentarily there has been a drawing together of the Western powers behind US imperialism. The moves by Finland and Sweden to join NATO are one indication of this. However, it would be a big mistake to think sustained unity on any longer term basis is on the cards.

The decline of US imperialism, the various capitalist crises, and the growing centrifugal forces as different national capitalist classes attempt to defend their own interests: these factors cannot be fully overcome. The US government’s sharp criticisms of the Tories threat to rip up the Northern Ireland Protocol as ‘endangering the united front against Russia’ is just one example of the conflicts that will erupt between the allies.

Look at the question of Europe’s reliance on Russian oil and gas, resulting in the EU countries putting €44 billion into Russian coffers since the war began. There are deep divisions on if, when and how that can be ended – between the EU and the US, but also within the EU. For Germany, for example, the cost of abruptly stopping Russian gas has been estimated to be €400 billion – 12% of annual output. And of course Putin knows that and is also stepping up threats to cut off supplies.

It is very unlikely that the NATO powers will get through the war and even more its eventual end game without deep divisions being revealed, not least on the terms for any peace deal. Even Germany’s moves to rearm are not simply about backing up US imperialism, but rather the drive to increase independent military strength in an unstable world where German capitalism’s interests will not always align with those of the US.

And on the other question – will the social base of Western capitalist leaders be increased by the Ukrainian war? Look at Britain. Johnson had managed to cynically use the invasion to momentarily distract voters from Partygate – but that phase is now over.

The same is true elsewhere. In Germany, the new government is in crisis, the biggest coalition partner, the SPD, has fallen in the polls. In France Macron won the presidency, but with the support of only 38% of registered voters, the lowest since 1969, the year after the general strike. And a big chunk of those who voted for him hated everything he stands for, but held their noses and cast their vote in order to block the right-populist candidate Marine Le Pen. Meanwhile in the US Biden’s approval rating is at a record low of 38%.

Falling living standards at the forefront

For the mass of the working class in the West Ukraine is a tragedy, and it is deeply worrying, but it is in the background compared to the overwhelming issue which is bearing down on everyone – the economic crisis of capitalism and the consequences for living standards.

The war in Ukraine has dramatically intensified the economic problems facing capitalism but it did not create them. The same can be said for the pandemic. The world is now facing ‘stagflation’ – a combination of stagnant economies and the highest levels of inflation in decades. There were a number of causes of the inflation, which had already begun to develop prior to the war. They include the surge in demand that took place as economies reopened, which was related to the consequences of the huge stimulus packages pumped in by all governments of major economies, in order to limit the effects of the Covid lockdowns.

Inevitably – just like the quantitative easing of the Great Recession era – the various stimulus packages led to huge bubbles on financial markets and mega profits for a few at the top. But while the big majority of the lucre still went to the capitalist class, some, unlike in 2008 – via furlough schemes and similar measures – did go into the pockets of the working and middle classes. That allowed some sections to accrue savings which – unlike the vast wealth of the rich, which tends to be sat on – resulted in an increase in spending once economies opened up. That, of course, was combined with the disruption to global supply chains created first by the pandemic and now massively intensified by the war.

That is not to suggest that these crises result from the pandemic or the war and are somehow separate from the inherent problems of capitalism itself. Far from it. Before Covid the world economy was already heading towards a new recession. And it was already utterly failing to deal with climate change, which led to a record 55 million being forced from their homes in 2020. It was already an ailing system. In a sense the historical justification for capitalism has been its development of the productive forces, and yet for decades massive profits have been combined with historically low levels of investment into the development of science and technique. That includes the super profits of the energy companies being combined with virtually no investment of any kind; least of all in the development of clean energy.

Prior to the pandemic levels of indebtedness were already at record highs with total debts – government, companies and households – over three times the size the global economy. That background of huge debts – with, for example, 20% of UK and EU companies being ‘zombies’ that are only able pay the interest on their loans – is an enormous complication for capitalist classes struggling with rising inflation now.

Moderate inflation is not necessarily a problem for capitalism. It is a means to make us, the working class, pay for the Covid crisis by lowering real wages. It is also a means to lower the level of historic debts in real terms. But the current surge in inflation, which is not under their control, risks undermining national currencies and with them different capitalist classes – as we can currently see graphically in Turkey. It is not on anywhere near the same scale but the value of sterling has also been falling.

Globally capitalist classes have no choice but to act. The usual response to inflation historically has been increasing interest rates, and steps are being taken in that direction. But that – especially given debt levels – risks triggering a serious new recession. It is fear of that which is the main cause of the turbulence on stock markets in last few days.

The previous era of low inflation, globalisation, and fat profits was based on the world balance of forces after the collapse of Stalinism, where briefly the US was dominant, and China did act as an assembly plant for the major powers.

That era is finished. As a result there is a general lack of room to manoeuvre for capitalist governments and central banks. They will always try to find policy measures to ameliorate crises, but each ‘solution’ will tend to very quickly create new crises. The most important conclusion for us to draw is that this is preparing the ground for massive social explosions.

Surging struggles

In Britain there has been a certain increase in the confidence and class consciousness of sections of the working class. This is combined with a very real feeling that there is no choice but to fight given falling living standards, with ten million predicted to be unable to pay basic bills by autumn. Those moods exist in every country, even though the absence of fighting trade union leaderships means that in most cases it does not yet have any clear expression.

Despite this we’ve seen first steps by workers to find a means to fight back. Like Macron’s re-election being met with the biggest May Day demonstration for years, the opening shots in the struggle to stop his attacks on the retirement age. Or the whole workforce of Amazon and its subcontractors in Italy – 40,000 workers – who successfully struck for union recognition and wage increases.

Where the organised workers’ movement fails to act it will not stop struggle, but it can lead to it having a more sporadic and confused character – like the ‘gilet jaunes’ (yellow vests) movement in France. Some on the left in Britain mistakenly condemned that movement as an indication of a move to the right by the French working class. Yet look what we’ve just seen in the presidential election. The left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon has limits, programmatically, and above all not having taken the opportunity since the last presidential election to start building a democratic workers’ party. Had he done so he would have been able to get into the second round.

Still he won 21.9% of the vote – 7.7 million votes – and came first among young people and in the working-class suburbs of many big cities. Meanwhile the Parti Socialiste (PS), the equivalent of Labour and once a party of government, was reduced to 1.8%. There is nothing guaranteed, but Mélenchon’s alliance – mixed character as it has – stands a chance of coming first in the forthcoming legislative election.

Every country has its own rhythm and characteristics. But many of the central elements of the processes taking place in France are pretty much universal, including here in Britain. Even if Labour wins the next general election because people are desperate to get rid of the Tories, by doing the bidding of the capitalist class over time it would suffer the same fate as the PS.

Here too, as Corbynism at its peak demonstrated, there is widespread support for a left, ‘socialistic’ programme. While objectively that potential still exists, right now – as a result of the defeat of Corbynism within Labour – no mass voice exists putting that programme. We’re doing vital work in the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) fighting for steps towards a new mass workers’ party, but mass forces have not – yet – moved decisively in that direction.

However, in every country a central fight in the next period will be for the working class to have its own independent political voice – its own parties, which we argue should be politically armed with a clear socialist programme. Just as we couldn’t beforehand have predicted where the first hesitant steps towards left parties were going to develop from in the era after the Great Recession – Podemos, Syriza, Corbynism and others – we also can’t say where new formations will spring from in the next period. But we can say that the intensity of the crisis, plus the hard experience of the retreats and betrayals of the first attempts at new left parties, will mean that the next wave will tend to develop on a higher level, with a more explicitly working-class character. And we can also say that we have a vital role to play in fighting for them.

Not a straight road

Of course the current absence of such parties leaves an enormous vacuum. Enormous accumulated anger against the existing order is combined with no effective outlet for it. In the US, that could result in the re-election of Trump, or a Trump-type candidate, in the next presidential election as a section of the working and middle classes vote to protest against the fall in their living standards on Biden’s watch.

That would be a nightmare for US imperialism, not only because they would have such an unreliable representative, but also because it would to lead to massive revolts of the working class and youth – a glimpse of which can been right now in the protests against Trump’s Supreme Court appointees threatening abortion rights. If a Trump-type candidate won, there is no doubt there would be huge areas of the US where the vast majority of the population would not have voted for the Republican candidate, as in all likelihood the majority of voters nationally would not have done. This reflects the ever-increasing dysfunctionality not only of the Republican Party but also of the whole US electoral system.

The growing polarisation of society in the US, the most powerful capitalist country on earth, is yet another indication of the ailing character of twenty-first century capitalism. We take very seriously the growth of right populist and far-right forces in different countries, but we also understand that the fight against them is not a separate task to the struggle for socialism. It is inevitable in this era, where governments acting in the interests of the capitalists are inherently unpopular, as illustrated by Biden’s plunge in the polls, that there will be capitalist politicians who are increasingly prepared to whip up racism, sexism, homophobia and nationalism in order to try and win or maintain power.

The fight for working-class parties independent of all capitalist politicians is therefore crucial to combating the right. It is not a new issue. But the intensity of the crisis means the need for such parties is posed more sharply now than ever, while it is also creating conditions where much bigger sections of the working class will be entering battle – which will also create the conditions for decisive steps in the formation of mass parties.

One hundred years ago, at the start of the twentieth century, Leon Trotsky, then a young man in exile in Siberia, wrote a short article describing an imagined conversation between an optimist and a pessimist. His description of what the new century had brought sounds very familiar today: “the poisonous foam of racial hatred”, “nationalist strife”, “rebellions of starving popular masses”, “hatred and murder, famine and blood”. Trotsky describes the new century appearing to try and drive the optimist into absolute pessimism, saying: “Surrender, you pathetic dreamer. Here I am, your long awaited twentieth century, your ‘future’.” But replies the “unhumbled optimist: You, you are only the present”.

Trotsky understood even then, at 21 years old, that there was an alternative to all the blood, misery and impoverishment of capitalism; that a new democratic socialist order could be achieved – not just by wishing for it – but by building forces capable of leading a struggle for it. That is our task today.