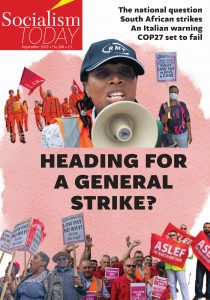

With even TV presenters talking about the possibilities of a general strike, things are definitely changing. HANNAH SELL looks at the historical experience of general strikes and the prospects for one of the most powerful weapons of the working class being on the agenda in Britain.

In Britain in 2017 just 33,000 workers took part in industrial action, the lowest level since records began in 1893. The numbers, at 39,000, were barely higher the following year. Against this background many on the left, including some who parted ways with the Socialist Party, turned away from the organised working class as the key force in the struggle to change society.

Now, in 2022, RMT general secretary Mick Lynch’s declaration that “the working class is back” is palpably true. The first national rail strike led to the Trade Union Congress (TUC) having a 700% increase in enquiries about how to join a trade union. Suddenly, the proud history of the working class in Britain is featured in the mainstream media for the first time in decades. The evening news has included references to the heroic revolutionary Chartist movement, to the 1926 general strike – the greatest show of strength to date by the British working class – and to 1972 when a general strike began to develop from below demanding the freeing of five London dock stewards jailed under the anti-union Industrial Relations Act.

Are we heading into events of a similar scale? Without doubt the workers’ movement is on an upward curve. Under the cover of the pandemic the government stopped collecting strike statistics, but it doesn’t require official confirmation to see that a major strike wave has begun.

The RMT national rail strike came after months of local strikes in different sectors, often organised by Unite. And the RMT strike alone involves more workers than the total number who struck in 2018. Other rail unions have also taken national action, as have CWU members in British Telecom, and now in Royal Mail, after a gigantic 97.1% vote in favour of striking.

Other national ballots are due to take place in the coming months. The largest nurses’ union, the RCN, is holding its first ever strike ballot in Britain, finishing on 13 October. A week later the UCU higher education ballot result is announced. The civil servants union, the PCS, has a ballot finishing on 7 November and the education union, the NEU, starts balloting in November. The biggest public sector union, Unison, has agreed to ballot in both health and local government, although there is no date yet in the former and the latter starts with a consultative ballot without recommendation.

There are other signs of increasing militancy, including the bus workers’ disputes across 47 companies at the last count, and the strike by Unite members at Felixstowe docks, an extremely powerful group of workers responsible for processing over 40% of all containers entering the UK. Also notable is the victory by the Coventry refuse drivers, who, in the longest strike in Unite’s history, over seven months succeeded in defeating the attempted strike-breaking by the Labour council.

There are also growing instances of unofficial action. These include the struggle by the industrial construction workers, with a record of militant strikes, but also the sit-ins, by the – up until now – largely unorganised Amazon warehouse workers.

Fuelling the strike wave is an enormous accumulation of grievances. Long term wage stagnation, severe cuts to public services, and then the pandemic – which dramatically sharpened class divisions – with the majority of the working class seeing that, while they did essential work, the elite were making huge profits from our misery. For many the corruption and hypocrisy of Johnson and his coterie summed up the behaviour of the whole elite.

All of this is the backdrop, but the immediate issue is soaring inflation, the highest in the G7 – not least because of crippling energy prices – leading to the worst fall in living standards since the mid-1950s. Wages have fallen 3% in real terms over the last three months alone. Strike action is the only means open to the majority of workers to combat this. When Mick Lynch appeared on TV programmes expressing the basic idea that all workers needed a pay rise and that they should fight for it, it electrified the country.

How strong is the class enemy?

As we head into a ‘hot autumn’ the whole of society is watching the unfolding drama. It is clear that Johnson’s replacement will be savagely anti-working class and aiming to inflict a defeat on the surging trade union struggle. The two groups of workers in the frontline – rail and postal – have been in the crosshairs of the capitalist class for a whole period. The government has so far spent millions in order to bail out the train companies during the strikes. This has conclusively demonstrated that the Tories’ Great British Rail initiative was not genuine nationalisation, but was designed to guarantee the income of the Train Operating Companies regardless of ticket sales, therefore freeing them up to try and defeat the rail unions. The government, and behind them the capitalists, are also determined to take on Royal Mail workers, whose 2019 overwhelming vote for strike action was blocked by the courts.

At the same time, Liz Truss, the most likely victor, is accumulating a long list of anti-trade union measures she has pledged to introduce within thirty days of becoming prime minister, such as needing to get 50% of an entire workforce to vote yes in order to strike, minimum service levels for public services, increasing the notice period for strikes from two to four weeks, and taxing strike pay. Rishi Sunak is competing with her to be just as rabidly anti-union.

However, it is also clear that next Tory leader will be heading an extremely weak, divided government, which has spent the summer publicly at each other’s throats, with “blood and thunder and eye-gouging” as former Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson put it. The pages of the serious capitalist press are full of unremitting gloom at the hopelessness of their political representatives.

Writing shortly after the gigantic workers’ struggles which dominated the early 1970s and defeated the 1970-74 Tory government led by Ted Heath, Militant (now the Socialist Party) drew a comparison with the general strike of 1926 saying, “the contrast between the wavering and bungling moves of the Heath government and the ruthless and determined tactics of Baldwin’s government in 1926 is another indication of the changed relationship of forces that exists today”.

Heath, however, appears a giant compared to the utterly inept figures that make up the current Tory Party leadership. A party that, during the period of British capitalism’s ascendency, was said to plan decades ahead, is now reduced to wondering how to get through the next five minutes. Clearly the working class can inflict defeats on this bunch of clowns. A serious struggle could very quickly force them out of office altogether.

However, the complete degeneration of the Tory Party is ultimately a reflection of the long, inglorious decline of British capitalism. Today its reserves and room to manoeuvre are far less than in the past. The British economy has historically low levels of investment, predictions of zero-growth at best this year, and is lagging behind every other major economy except Russia. Therefore, regardless of the weakness of its political representatives, the capitalist class will be impelled to try and make the working class pay for the multiple crises it faces. There is no prospect of a prolonged period of social peace. Nor are the Tory Party the only political representatives available to British capitalism to carry out its programme. Unlike in the Corbyn era, they can rely on Starmer’s ‘New Labour’ to do their bidding if elected.

We are at the start of a new era of more intense class struggle. The current round of strikes can play an important role in shaping that era, but there is no result which could prevent them being the beginning, and not the end, of a period of increased working-class combativity. Successes for the trade unions in the current battles would relieve the desperate cost of living squeeze and enormously strengthen the confidence of the working class, but new battles would quickly arise as the bosses renewed their attacks. On the other side, even if the current wave of struggle does not lead to clear victories for workers, or even if defeats are suffered, we would be likely to see at most a pause, a drawing of breath, before new conflicts erupt.

The strength of the workers’ movement

Certainly, despite the weakness of the Tory government, and the great potential strength of the workers’ movement, victories in the current rounds of struggle are not guaranteed. The “ruthless and determined tactics” of Tory premier Stanley Baldwin in 1926 would not have resulted in a victory for the capitalist class without the failings of the leaders of the workers’ movement, and today as well the strength of the workers’ movement, and the character of its leadership, are the key questions.

Comparisons have been drawn with the 1970s. While some are valid, this is a very different period. Then the working class was in an exceptionally powerful position. A combination of factors, including the world balance of forces in the cold war era and the rapid economic growth of the post-war upswing, created a situation where the capitalist class was forced to make significant concessions to the working class. In 1979, 53% of workers were union members and, in 1980, around 70% of employees’ wages were set by collective bargaining. In the mid-1970s there were at least 300,000 shop stewards in Britain.

In the decades afterwards the working class suffered serious defeats in Britain and on a global scale. The Stalinist regimes that had existed in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe bore no resemblance to genuine socialism, but based on a distorted form of a planned economy they still represented a threat to capitalism. Their collapse enormously accelerated a worldwide offensive against the working class, with the capitalists restoring their profits at our expense. Privatisation of state industries, huge cutbacks in state welfare spending, and an assault on established trade union strength were the order of the day. The era of globalisation – in reality the increasingly unfettered global movement of capital – was used to bludgeon workers’ wages, terms and conditions in the ‘race to the bottom’.

While the fundamental strength of the working class remained intact, in 2020 only 23.7% of workers were members of trade unions. Nonetheless membership was 6.5 million, making trade unions by far the biggest democratic workers’ organisations in the country, and the first means of defence for workers moving into action.

Many capitalist commentators point towards ‘deindustrialisation’ to argue that the working class in Britain today has no collective power. However, while the structure of the economy has changed, the potential power of the working class remains. Today, for example, manufacturing makes up less than 10% of the UK economy, the lowest proportion of any country in the G7. However, those manufacturing workers still have huge potential strength. There is a third as many car workers in Britain today as in the 1970s, but increased productivity mean they still produce the same number of cars. Meanwhile, the weakness of Britain’s manufacturing sector leaves it particularly reliant on imports, which overwhelmingly come through Britain’s ports. The defeats of the past, and the implementation of containerisation, have resulted in far fewer dock workers today than in the 1970s, but they too have enormous power as the Felixstowe strikers are demonstrating.

Transport workers continue to play a key role in the economy. At the same time there are new cohorts of the working class, with the Amazon workers, 75,000 strong, as the ‘prime’ example, with potentially considerable industrial muscle and just beginning to organise. Other sections of society – the majority of whom in 1926 and to some extent in the 1970s were hostile to the working class – have had their living conditions undermined and are increasingly looking to working class methods of struggle as the current action by barristers graphically illustrates.

Trade union membership increased year-on-year for the four years up to 2020, and has certainly accelerated since. But we will not see a return to the more stable high levels of trade union membership of the 1960s and 1970s, which was possible due to the class balance of forces at that time and the long post-war boom.

We are heading into a period of huge class battles, nonetheless. There is no direct correlation between union density and the scale of struggle. In 1926, during the general strike, 5.3 million were members of trade unions, just under 30% of workers. The numbers had been higher. In 1919 a massive 35 million days were lost to strike action, and union membership peaked at 8.3 million in 1920. However, the deep slump of 1921-22 led to soaring unemployment. The failures of the right-wing trade union leaders allowed savage cuts on workers’ terms and conditions, and a sharp fall in union membership. Yet none of this prevented the general strike.

Today, while absolute union density is broadly comparable to 1926, levels of cohesion and workplace organisation are not as yet close to the levels prior to the general strike. At that stage a quarter of all trade unionists were aligned with the National Minority Movement, in which the Communist Party played a leading role and which aimed to act as a rallying point for left and revolutionary elements in the trade union movement. The proportion of trade union activists was far higher than is currently the case.

The number of stewards was also much higher in the 1970s. In 1980, for example, there were 328,000 workplace representatives, of whom 174,000 were in the private sector. By 2004 that figure had fallen to 128,000, with only 56,000 in the private sector. In the eighteen years since there is no doubt the number of workplace representatives has fallen much further, particularly under the impact of the 2016 anti-union legislation – which cut rights to facility time for trade union duties. Unison, for example, the biggest public sector union with 1.3 million members, estimated that last year there were only 12,000 members active in its structures.

However, the number of shop stewards was also relatively low – despite high union membership – in the 1960s; it was the surge in struggle which forged a new generation of workplace leaders, leading to a doubling of the number of shop stewards in manufacturing between 1966 and 1976. The same process has begun today. While union membership may fluctuate along with the rhythm of struggle, the new generation of fighters that are beginning to gain experience now have the potential to transform the trade union movement.

Socialists have a vital role to play in helping to cohere the new forces currently joining the trade unions into consistent fighters to transform their unions, as well as winning them to the struggle for a new society. The beginning of the development of combines in Unite, under the leadership of Sharon Graham, has the potential to aid this process by bringing together stewards across particular sectors. Trades councils, often little more than empty shells in recent decades, could now start to take on life and coordinate struggles at a local level. In addition the National Shop Stewards Network, with nine unions affiliated to it, has the potential to be filled out and to play a critical role in the next phase of struggle. Also important will be the development of left organisations within specific unions, campaigning for fighting policies under the democratic control of the membership, including calling for trade union officials to be regularly elected, subject to recall by their members and paid a worker’s wage.

Next step coordinated action?

What will the next phase be? Is a general strike on the agenda? The TUC congress, taking place in the second week of September, has a number of resolutions – including from the RMT, PCS, Unite, Unison and the NEU – which call for the TUC to “coordinate a campaign of industrial action across the public and private sector to win pay rises”, and other similar proposals. Up until now Frances O’Grady, the outgoing TUC general secretary, has abdicated responsibility, saying that she wouldn’t ‘rule out’ coordinated strike action, but “workers are coordinating themselves, not out of any deliberate strategy”.

Striking together isn’t a principle in and of itself. No-one should suggest that any of the groups of workers currently involved in strikes should stop prosecuting their own struggle in order to wait for coordinated action. Nonetheless, generalised coordinated strike action can play a very important role in raising the consciousness and confidence of the working class – acting together ‘as a class’ – on the one side and, on the other, act to cow and undermine the confidence of the capitalist class.

At this year’s TUC congress there will be the greatest pressure for coordinated action since at least 2011. The coordinated action that took place then was significant, and could have led to the ousting of Cameron’s government were it not for the retreat of the right-wing trade union leaders. Nonetheless, this time the struggle is potentially broader and more deep-rooted. Then action was focused overwhelmingly in the public sector, and was mainly one-day ‘protest’ strikes. Now action is across the economy and many of the strikes that have taken place are of a more sustained and serious character.

However, there is not yet any concrete proposal for coordination. An essential part of the role of Marxists is to argue for the next material steps needed to take the movement forward. The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky commented on the 1925 TUC congress that, “the resolutions of the congress were the more to the left the further removed they were from immediate practical tasks”. Phrases about coordination are important, and reflect the pressure from below, but the right-wing TUC leadership will do all it can to resist them being turned into meaningful action.

The TUC has, however, called a lobby of parliament for Wednesday 19 October, although the leadership sees it as a small scale ‘polite’ lobby of MPs. However, turning this into a massive midweek demonstration, with an appeal to as many workers as possible to attend, and all live strikes coordinating their action on that day, would be a powerful warning to the new Tory prime minister. Such a mass mobilisation should be organised around a programme of demands that could appeal to broad sections of workers and young people. Central would be opposition to the anti-trade union laws, but also including inflation-proofed pay rises for all, a minimum wage of at least £15 an hour, nationalisation of the energy companies, and living pensions and benefits. Without question such an approach would help to draw into active participation the millions who are currently looking towards the trade unions, and be an important step towards a 24-hour general strike.

Twenty-four hour general strike

During the wave of struggle that followed the 2008-2009 great recession many one-day general strikes took place in some southern European countries: there were more than 30 in Greece alone. Now they are just beginning to come onto the agenda again. In countries with a tradition of one-day strikes the trade union leaders can accept them as a means to let off steam. In Britain, however, even a 24-hour general strike would be a big step forward and of immense importance in helping to prepare the working class to carry through decisive action to defeat the capitalists.

At this stage the Socialist Party argues the case for a 24-hour general strike, and puts forward slogans like ‘all strike together’ that point in that direction. We also have to recognise, and explain how to overcome, the obstacles that exist to such a strike. The already-existing repressive anti-trade union laws have slowed down the moves towards strike action in many of the big unions. In a number of unions, including PCS and the NEU, Socialist Party members have been campaigning for many months for a national lead to build for strike action, which would have enabled earlier ballots. However only now, under pressure from below, have their leaderships moved to ballot, meaning that legal coordinated strike action involving the big majority of unions balloting will not be viable before the late autumn at the earliest. However, turning the 19 October TUC lobby of parliament into a mass midweek demonstration would be an important step in that direction.

Openly resisting the anti-trade union laws on a mass basis is posed in the next period, especially if the Tories try to introduce a new raft as they are likely to. Growing numbers of workers are already moving to take unofficial action and, as in past struggles, at a certain stage it will be mass defiance that renders the anti-union laws powerless. The Emergency Powers Act of 1920 could not prevent the 1926 general strike. In the early 1970s Heath’s Industrial Relations Act – under which the five London dock stewards were imprisoned – was made toothless by the powerful strike that developed from below and won their release.

Nonetheless, at this stage the existing anti-trade laws are seen by the majority of trade union activists as an objective fact which has to be ‘worked around’ in order to have some limited legal protections when striking. With no counter-arguments prepared by the leadership in advance, generally there is not the confidence to ignore the cumbersome process of campaigning to win and get the necessary turnouts in national ballots. Such are the undemocratic character of these laws that, despite huge anger over the cost of living, it is not guaranteed that all the big general unions will meet the turnout thresholds for legal action. In such cases tactics like disaggregated ballots, alongside the national ones, can help to ensure that strike action can still take place.

However, ultimately the anti-trade union laws cannot be allowed to prevent the struggles that are needed to defend workers’ interests. If any of the unions currently involved in struggle are threatened by the government and the courts – under existing or new anti-union laws – the whole of the workers’ movement would need to come to their defence. That would urgently pose the need for a 24-hour ‘warning’ general strike. If the TUC did not call action, the left union leaders would need to form a coalition of the willing to do so and, while taking whatever action is needed to try and preserve the legal protections underpinning trade union organisation, not be constrained by them.

Why not an unlimited general strike?

Why stop at 24 hours? Wouldn’t it be more ‘revolutionary’ to call for an all-out general strike? It is not the job of Marxists to just advocate the most ‘radical’ sounding demand possible at each stage, but to weigh up concretely the stage of the struggle and what steps are needed to take it forward. As Trotsky explained, calling for an all-out general strike – which is on a far higher level than a one-day strike – “requires a painstaking Marxist accounting of all the concrete circumstances”, especially in “the old capitalist countries”. In some circumstances, he explained, “there are conditions in which a general strike may weaken the workers more than the immediate enemy. The strike must be an important element in the calculation of strategy and not a panacea in which is submerged all other strategies”.

There are times when the ruling class is frightened by the scale of a general strike movement and quickly makes concessions. That was the case in Russia in 1905, for example. However, once an-all out general strike develops, if the working class is not able to take power into its hands, then the capitalist class can inflict a defeat on the working class which takes a period to recover from. The scale of the defeat in 1926, when the TUC leadership capitulated after nine days, was limited by the heroism of the many workers who stayed out after the strike had been called off in order to win guarantees against victimisation. Nonetheless, the impact of the defeat was considerable.

However limited the issue around which a general strike is called, once it has begun it has its own logic and cannot be kept within narrow, partial aims. Its being called reveals a fundamental conflict between two opposed classes contending to reorganise society. Once it is underway the question is posed even more sharply. In 1926, despite the TUC leadership’s desperate insistence that the general strike was not political, on the ground workers were beginning to take steps towards running society. This is vividly described in Peter Taaffe’s excellent book, 1926 General Strike: Workers Taste Power. Around 400 trades councils and over a hundred councils of action organised at local level and began to coordinate with each other. In the strongest areas the government’s representatives had to come, cap in hand, to beg the workers’ organisations for permission to act. Lorries had to carry posters saying ‘by permission of the TUC’.

In an unlimited general strike, as the working class moves to take things into its own hands, and the ruling class feels the levers of power slipping out of its grip, the problem of power – of which class will run society – is unavoidably posed in immediate practical terms.

Britain’s capitalist class understood that was on the agenda in the 1920s. They also understood that the leadership of the TUC was terrified of power. Prior to 1926 the British prime minister, Lloyd George, told the trade union leaders in 1919, “if you carry out your threat and strike you will defeat us, but if you do so have you weighed up the consequences? A strike will be in defiance of the government of this country, and, by its very success, will precipitate a constitutional crisis of the first importance. For if a force arises that is stronger than the state itself, they must be ready to take on the functions of the state, or withdraw and accept the authority of the state. Gentlemen, have you considered, and if you have, are you ready?” As one right-wing trade union leader admitted, “from that moment on we were beaten”.

The majority of the trade union leaders of the time were not prepared to mobilise the working class to take power. The right only called the general strike because they understood that if they did not it would develop from below, outside of their control. However, even the very best of the left leaders, like the miners’ leader AJ Cook, did not have a clear idea of how the working class could take power, seeing industrial militancy alone as enough.

And today

This is still ahead of the outlook of the left wing of the TUC today, however, who in general see the current wave of strike action as a means to fight the immediate cost of living crisis, but do not see any possibility of systemic change. Some hope to be able to kick out the Tory government, which would be welcomed by millions of workers, but do not tackle the problem that, as Mick Lynch has put it, “Starmer’s Labour could be another version of the Tories”. Mick has referenced the revolutionary general strike of Chartists. However, the Chartists were demanding the right to vote but in order to build a society in the interests of the working class, not to vote for different brands of pro-capitalist politicians which is the situation facing the working class today.

One of the important defeats suffered by the working class in the period after the collapse of Stalinism was the transformation of Labour from a ‘capitalist-workers’ party’ (with its leaders susceptible to pressure from the working-class base of the party via its democratic structures) into New Labour, an out-an-out capitalist party, which was considered by Margaret Thatcher one of her greatest achievements, because there were now two major parties that capitalism could rely on to govern. Briefly, during the Corbyn era, there was an opportunity to transform Labour into a party of the working class. However, following Corbyn’s defeat, the pro-capitalist New Labourites have a more iron grip on the party than ever, with undemocratic rule changes pushed through to ensure there cannot be a repeat of Corbyn’s election as leader.

Of course it is true that, if the Tories are finally ejected from office as a result of a strike wave, an incoming Labour government would be under pressure from a resurgent workers’ movement. But that doesn’t mean that Starmer’s New Labour would act in the interests of the working class under that pressure. His reason for abandoning public ownership, for example, is not that it isn’t popular. On the contrary, the most recent polls show that 66% of the public – including 62% of Tory voters – support nationalisation of the energy companies, yet Starmer has repeatedly and pointedly refused to call for it. His priority is to demonstrate to the capitalist class that he is ‘their man’.

A New Labour government acting in the interests of big business during the next period of developing capitalist crisis, will be compelled to take far more brutal anti-working class measures than in the Blair era.

Unfortunately, none of the national trade union leaders have yet tackled this question. The most militant have sharply criticised Labour. Unite general secretary Sharon Graham, for example, withdrew funding from Midlands Labour council candidates over the Coventry bin strike. However, for her the political issues are mainly for the future and her focus is not to “let the political tail wag the industrial dog”. For many workers, who can see no possibility of them having their own political party at this stage, this resonates, but no long-term victory for the working class can be won by industrial action alone. The ‘industrial dog’ will need its own political voice if it is to take power out of the hands of the capitalist class and begin to build a new socialist society.

The development of a mass workers’ party, politically armed with a socialist programme, will be an essential element in the working class getting ready for the seismic struggles ahead, which at a certain stage could include a general strike.

Posing the question, but not giving the answer

However, a general strike alone is not sufficient for the working class to take power; it poses the question but does not answer it. For that a programme for the working class to take power is necessary. This in turn requires the development of a mass party with a revolutionary programme and a tested leadership.

In 1926 the young Communist Party of Great Britain had around 4,000 members before the strike, plus considerable influence via the Minority Movement. Although it was a small force it nonetheless could have had a much greater influence on events had it put forward a clear programme, strategy and tactics, and had been prepared to criticise the mistakes of the trade union leaders, including those on the left, instead of acting as cheerleaders for the latter. The Communist Party’s main slogan, “all power to the TUC general council”, summed up their wrong approach and contributed to politically disarming the most advanced sections of the working class.

Today as well the role of Marxists is not to uncritically tail end even the most left wing of trade union leaders, but rather to put forward at each stage a clear, independent class struggle programme linked to the need for the socialist transformation of society. With that approach, during struggles ahead wide sections of the working class can be won to a Marxist programme and the fight for socialism.