Keir Starmer launched the Labour Party’s campaign for the May local and mayoral elections in England on March 11 by majoring on Boris Johnson’s plan for a 1% rise-but-real-terms-pay-cut for nurses and other NHS workers.

This line of attack on the Tories was chosen even though, as the BBC report archly put it, “NHS pay for England is decided nationally, rather than by councils”.

Yet even then, on his chosen field, Starmer avoided media questions about whether he would join nurses on a picket line or what he felt would be an appropriate pay rise, other than saying that the 2.1% previously agreed in 2019 would be ‘a good starting point’.

But what about the council elections? A National Audit Office (NAO) report had been released the previous day showing that 94% of English local authorities expect to cut spending in the year ahead after the hit to their finances from the Covid pandemic. Yet nothing was said on what Labour-led councils would do under Starmer to resist the coming turbo-charged austerity against local public services.

The position facing councils is indisputably dire. Years of austerity mean that the 2021-22 settlement funding for local authorities in England as a whole will have decreased in cash terms by 30% since 2015-16 (while council tax rises will take in an extra £2 billion this year, predominately from workers’ pockets). And on top of this there are the extra costs of the past extraordinary year.

The Johnson government, in another example of what it can be forced to do when outside factors impel it, has provided an extra £9.1 billion to prevent a complete collapse of council finances.

In the last financial year local authorities spent an estimated additional £6.9 billion on Covid-related services – personal protective equipment, housing rough sleepers, support for those shielding at home, public health support for testing, track and trace, and so on – while losing £2.8 billion from fees, charges and other non-tax income.

But the Covid funding deficit is still £600 million. Nearly a third of local authorities will see a gap between their extra Covid costs and their additional government funding equal to 5% or more of their revenue spending. What should be done?

Labour-led Manchester city council is projecting cuts of £41 million this year, Newham and Newcastle £43 million and £40 million respectively by April 2023, and Leeds £87 million, “the single biggest amount to be taken out of its spending since the start of austerity” says The Guardian (1 March).

Starmer’s main theme at the election launch, however, was not to address this crisis but to prove once again the distance between himself and Jeremy Corbyn, emphasising that “this is a different Labour Party, under new leadership”.

Corbyn, it is true, fatally failed to confront the councillors inherited from the New Labour era – over 90% of whom did not support him for leader – with the demand to refuse to implement cuts to local public services. Instead, in one of the first of many mistaken attempts to find ‘unity’ with the pro-capitalist Labour right, a circular letter was sent with John McDonnell to council Labour Groups in December 2015 which The Guardian gleefully hailed as ruling out a “re-run of 1980s defiance over cuts”.

The resulting continued experience of cuts made by alleged ‘Labour’ councils allowed the town hall Blairites to undermine Corbyn’s anti-austerity message, particularly amongst working class voters in ‘left behind’ Labour constituencies.

But Starmer’s revived New Labour no longer even pretends that it is anything other than an alternative set of managers of capitalism and its austerity demands, locally as nationally.

Cracks in the edifice

Yet even the right-wing dominated Labour local government edifice is beginning to crack, revealed most acutely in the recent turmoil in Liverpool council and the city’s Labour Party.

Late last year the Labour Mayor of Liverpool, Joe Anderson, in office since the directly-elected post was first established in 2012, was arrested on suspicion to commit bribery and witness intimidation.

The government launched an inspection of the council’s planning, regeneration and property management functions, with rumours that these may be taken over by commissioners. Anderson denied any wrongdoing but stood aside from his mayoral duties, and withdrew from this year’s mayoral election.

Since then the Liverpool Labour Party has been involved in a process to select a new mayoral candidate. This has seen an initial shortlist of three sitting councillors overturned; a court challenge against the Labour Party, unsuccessful, by one of those excluded councillors, Anna Rothery, who had drawn the backing of Jeremy Corbyn and the national Unite union for her candidacy; and the subsequent imposition of just two candidates – both right-wingers – in a new selection ballot, with the result of that not due until the day official nominations open on March 29.

The Liverpool crisis is a product of many factors, including the abuse of power encouraged by the ‘executive mayor’ model of local government, championed by both the Tories and the New Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

They saw it as a move to a US-style system of local government, raising one individual above a wider group of councillors who have to justify themselves to a more local ward electorate, making it easier for the ‘town hall Bonaparte’ to take unpopular decisions to cut or privatise services or to favour business interests.

That is why the Socialist Party opposes council executive mayors and calls for their abolition, including where our members, as part of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC), stand in mayoral contests.

But the root of the Liverpool crisis is the desperate position facing the council finances and local public services in the city, which has seen the Liverpool Labour Mayor and councillors administer £420.5 million worth of budget cuts and tax rises from 2011 to 2020.

The budget for 2021-22 includes further cuts of £15.4 million and a 4.99% council tax rise. The trigger of Anderson’s fall has brought all the subterranean tensions this situation has created to the fore.

Anna Rothery has been a backbench Liverpool councillor since 2006 as the city’s public services were being decimated. But, not least by standing up to Starmer to call for Jeremy Corbyn’s reinstatement to the Parliamentary Labour Party, she has become the conduit for the accumulated anger in the Liverpool labour movement.

As we go to press, however, it seems that she has not responded to calls to discuss standing as an independent working class anti-cuts candidate in the mayoral contest, with that banner now to be carried by the former UNISON public sector union national executive council member Roger Bannister, representing TUSC.

But the episode overall shows that, in the vacuum created by the new era of crisis opened by the Covid pandemic, combined with the defeat of Corbynism within the Labour Party framework, all types of new developments and political metamorphoses are possible – likely, in fact – as the working class seeks a way forward.

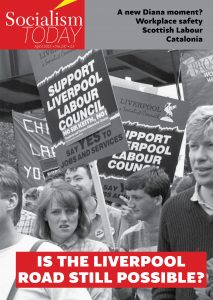

Is the Liverpool road still possible?

Roger Bannister is also a veteran of the successful 1980s Liverpool struggle against the Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher, the secretary at the time of the Liverpool Broadgreen constituency Labour Party represented by the Militant MP Terry Fields, and expelled in June 1986 as part of the then Labour leader Neil Kinnock’s purge of the Liverpool District Labour Party.

But is the Liverpool road still relevant? Hasn’t the situation completely changed since then, the argument goes from those not prepared to fight? Didn’t even John McDonnell say in the circular letter that council chief finance officers now have the legal power to set budgets themselves over the heads of councillors and “there is no choice for them anymore”?

This edition of Socialism Today is carrying an abridged version of an article by Peter Taaffe first published in the spring 1986 edition No.31 of our predecessor magazine, Militant International Review, providing a real time analysis of the historic example of a city council that was prepared to fight.

It answers in advance – from 1986! – John McDonnell’s argument, which is referring to the idea of councils not setting a budget at all. As Peter Taaffe makes clear this was not the tactic proposed by Liverpool in 1985, which went along with it only “in the interests of a united front against the government” of 20 Labour councils, “notwithstanding their misgivings on the ‘no rate’ policy”.

It is true that council chief finance officers now have greater legal powers than the Liverpool city treasurer had in the 1980s to block council expenditure or refuse to issue council tax bills – through a Section 114 notice – if they deem a council budget to be ‘unbalanced’.

In Liverpool notices for payment of rates (the local tax levy of the time) were issued on the basis of a deficit budget set by the council. But nobody today is proposing not setting a budget at all or setting a deliberately ‘unbalanced budget’.

But ‘balancing’ a no-cuts budget by the use of prudential borrowing powers and reserves, to buy time to build a mass campaign for government funding, is a different matter.

This is the strategy, building on the lessons of Liverpool, that has been pioneered by TUSC, in which the Socialist Party plays a leading role, and which has won support particularly in the local government workers’ unions.

This would not avoid a potential confrontation with council chief finance officers or the government. The alternative budgets that were presented by TUSC-supporting councillors in Southampton, Hull, Leicester and Warrington, and the example they were based on – the budget moved by Socialist Party councillors in Lewisham in 2008 – were not recommended by council officers.

But they were not ruled as ‘illegal’ either. The use of borrowing powers and reserves to meet projected deficits is a ‘matter of judgement’ for councillors to make, which could at least be legally defended while a mass campaign of opposition to the cuts is built.

The Covid crisis has shown the room for manoeuvre that still remains. The NAO report records that nearly a quarter of councils will ‘materially overspend’ the budgets they set at the start of the 2020-21 financial year which were, at the time, formally ‘balanced’.

The Department of Housing, Communities and Local Government has issued exceptional ‘capitalisation orders’ to several councils, allowing them to use capital funds for day-to-day spending.

The Labour Party in local government is not powerless. The 120 or so Labour-led councils have a combined spending power greater than the individual state budgets of 16 European countries.

They are a potential alternative power that could compel Johnson into yet another funding U-turn, if they were prepared to fight. The ‘technical’ means to do so can always be found.

Rebuilding after Corbynism

It is true that local austerity will not be defeated by action in the council chambers alone but by combining such defiance with building a mass movement, as the Liverpool struggle showed.

But that is a matter of political programme and will and Starmer, a defender of capitalism, is determined to reassure the ruling class, spooked by the mass expectations raised by Corbyn’s leadership particularly amongst the youth, that their interests are safe.

On cue the architect of New Labour, Lord Mandelson, while praising Starmer – he “radiates competence” – has called for a clear out of Corbyn’s policies as the next step to take, as the new leader “still has the 2019 manifesto around his neck” (BBC News, 21 March).

It will be another missed opportunity to challenge Starmer’s revived Blairism if, as seems likely, neither Anna Rothery in Liverpool nor Jeremy Corbyn himself in London, contest the mayoral elections this May on a fighting anti-austerity platform.

The electoral challenge mounted by TUSC, having only relaunched in September but with over 300 candidates standing in the traditions of the historic Liverpool struggle, will only be able to offer a glimpse of the potential that would be there – if the left trade union leaders, and any of the Campaign Group MPs and supportive councillors prepared to join them, took a clear and decisive lead.

Realising that potential to the full is the task of our time.