Sir Keir Starmer’s leader’s speech at this year’s Labour Party conference “was more John McDonnell than Tony Blair”, the former shadow chancellor under Jeremy Corbyn told the fringe meeting organised at the Liverpool gathering by the Socialist Campaign Group of left Labour MPs.

“It demonstrated just what you have done throughout our movement” McDonnell said, praising the dwindling minority of left-wingers remaining within Starmer’s new New Labour party. “By sticking around, you’ve forced our ideas onto the agenda again” he claimed, “so even the Blairites have to accept them”. (BBC News, 28 September)

Others joined in, pointing to the conference votes for a £15 an hour minimum wage and at least inflation-linked pay rises; a “commitment to a publicly-owned railway” proposed by the ASLEF train drivers’ union; and the resolution – moved by the Communications Workers’ Union (CWU) general secretary Dave Ward as the bitter dispute of the postal workers raged on – that “the next Labour government will bring Royal Mail back into public ownership”.

Describing policy announcements such as Starmer’s plan for a state-owned Great British Energy company as “genuinely transformative” and a “victory for the left”, the Nottingham East MP Nadia Whittome appealed to “those with power in our party” to recognise that “the left are not the enemy, we are the future”.

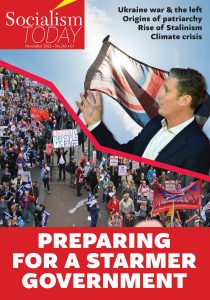

With the Tories’ unfolding – and unfinished – implosion producing an average opinion poll lead for Labour of 33% by mid-October, up from 8% in the days before the then chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s notorious ‘mini-budget’, Starmer could well win a government majority even of 1997 proportions in an election at any point over the next two years.

But is dressing up Starmer’s unambiguous restoration of New Labour-style pro-capitalist politics within the party after the defeat of Corbynism really preparing the working class, and particularly the most militant activists, for the stormy times ahead?

One outcome of the next general election, if even a couple of the fighting trade unions like the CWU, the RMT transport workers union or Unite organised an independent working class candidates’ list, could be to get at least a small block of MPs elected – unbound by the Labour whips – from which to challenge a Starmer government’s inevitable Tory-lite austerity policies.

This would have a far greater impact in the struggle for workers’ interests than lining up behind every ‘official’ Labour candidate (while not opposing, of course, the handful of left MPs and candidates who do manage to be selected for Labour). Surely this would do more to get the socialist ideas necessary to defend the working class ‘onto the agenda’ than the left in general, and the left unions in particular, ‘sticking around’ for individual policy gains – contestable in their value at that – in Starmer’s now thoroughly capitalist party?

Blair came to power in May 1997 with the UK economy recovering after the recession of 1990-1992. In fact the 4.9% rise in GDP for that year became the peak growth rate recorded during the subsequent 13 years of New Labour government.

This was against the benign backdrop – for capitalist politicians not the working class – of the broad shift in the balance of class forces that characterised the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Stalinist states of Russia and Eastern Europe from the late 1980s.

Feeding capitalist globalisation through the opening up of new markets and cheap labour, capitalism’s ‘ideological victory’ also impacted on the combativity of the organised working class, in contrast to the revival of working class struggle being seen today. This is not 1997.

Nor is it 2010. Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England then, has recently warned of a “more difficult” era of austerity to that pursued in the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government of David Cameron, the Tory chancellor George Osborne, and the Liberal Democrat leader and deputy prime minister Nick Clegg, which made the deepest cuts in public spending since 1945.

Meanwhile Starmer and his shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves, who previously worked as a Bank of England economist, could not be clearer in their commitment to ‘sound finance’ – in other words, to follow the dictates of the ‘markets’ for austerity in this new era of global capitalist crisis.

A more serious analysis is needed on how the working class can have its interests politically represented in the events ahead than the wishful thinking displayed at the Campaign Group rally.

Starting with a realistic assessment of what happened at Labour’s conference and what it signified.

Blairism triumphant

The Campaign Group meeting opened with a reprise of the White Stripes’ Seven Nation Army song but this time with the chant, ‘Oh, Zarah Sultana’, for the Coventry South MP who has recently seen off a deselection challenge, a small victory for the left.

But the irony that the object of the original adaptation of the song, Jeremy Corbyn, not present at the meeting, had had his exclusion as a future Labour candidate endorsed by the conference, didn’t seem to register.

A move for a rule-change to allow Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) to be in control of who their candidate is rather than the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) was one of the first conference debates, and its outcome showed more clearly than the policy sessions could how securely Blairism has re-entrenched itself.

Proposed by Islington North CLP, whose MP is a certain local Labour Party member called Jeremy Corbyn – who is suspended from the PLP – the constitutional amendment was opposed by the Labour Party National Executive Committee (NEC) and put to a card vote.

Just under 60% of delegates duly voted against the effective re-adoption as a Labour candidate of the party’s leader at the general election less than three years ago.

The actual policy positions adopted by the leadership were also far less than they have been presented by the Labour left.

Even before the conference, when over the summer Starmer announced that “what we’ve done with the last manifesto is to put it to one side. We’re starting from scratch. The slate is wiped clean” (The Guardian, 29 June), he distinguished between the 2019 commitments to the re-nationalisation of water and energy, and nationalisation of the railways.

“I take a pragmatic approach rather than an ideological one” he said, explaining in a Daily Mirror interview that “rail is probably different from the others because so much is already in public ownership” (25 July).

But this is not a commitment to immediate re-nationalisation. As the shadow transport secretary Louise Haigh confirmed to the conference, the remaining train operating companies would be taken back into public ownership but only as their contracts expired, with five franchises not ending until 2025 or later.

A mixed system would remain, potentially for a full parliamentary term, unless a Starmer government was forced to act. Glossing over the reality does not help prepare the movement for that battle.

Similarly, the Great British Energy plan “is not about nationalisation”, a Labour spokesperson emphasised after its conference launch (The Guardian, 28 September).

Instead the proposal is to create a publicly-owned energy generation company, with a remit to invest in clean energy such as wind, solar and tidal, competing against the existing firms operating in the energy market (while carrying the high-cost overheads and unsafe legacy liabilities of nuclear power).

Starmer’s ‘pragmatic approach’ ultimately leaves economic power in the hands of the capitalists, with their imperative to maximise profit ahead of social and environmental need predominating.

The left did recognise that a conference vote does not guarantee a policy’s inclusion in the general election manifesto, which is decided at a ‘Clause Five’ joint meeting of the NEC, the shadow cabinet, the national policy forum officers and so on – so named after the relevant part of Labour’s constitution – convened when an election is called.

And their argument that overcoming this obstacle is not a new issue is also correct.

The battle to end the effective veto over the manifesto the Clause Five process gives to the leader was part of the constitutional changes – alongside the mandatory re-selection of MPs and the election of the party leader by a wider electorate than the PLP – fought for by the left in the early 1980s, including by Militant, the predecessor organisation of the Socialist Party. In his diaries Tony Benn records contributions at critical meetings by Tony Saunois, then a Labour Party Young Socialists rep on the NEC, now the secretary of the CWI.

But at that time the organised working class had democratic avenues within the Labour Party through which, potentially, its interests could be enforced (the trade unions elected 18 out of the 28 NEC members then, 13 out of 39 now).

Mistakenly, neither the political expunging of Blairism and the Blairites nor the democratic transformation of the party’s structures was carried through in the four-and-a-half years of Corbyn’s leadership.

The Clause Five hurdle was only overcome by Corbyn in 2017 by appealing over the heads of the right with the leaking of the draft manifesto, who were then confronted with a fait accompli. The situation today, of course, is completely different.

When both US president Joe Biden and the International Monetary Fund criticise ‘trickle down’ policies, while the UN Conference on Trade and Development annual report calls for price controls, windfall taxes and more regulation to combat global inflation, a new energy company and the other tweaks to the market proposed by Starmer and Reeves are not ‘transformative’ policies but acceptable variants – to the ruling class that is – of orthodox capitalist economics.

All Labour’s conference showed is that, having decisively defeated the spectre of Corbynism, Starmer and the right are more confident in their role as an alternative management team for British capitalism.

The former Tory leader William Hague concluded that Liz Truss and Kwarteng’s “mini-budget and its rapid disavowal shows that both Tories and Labour have very little room for financial manoeuvre”, which is true for any government remaining within the confines of capitalism.

“Without a huge ideological divide”, he went on, “the next election is likely to focus on competence and compassion”. (The Times, 18 October) Starmer’s Labour is not a vehicle through which the working class can achieve the political representation of its interests.

A workers’ list

Responding to the pledge of support for public ownership of the railways made by Labour’s shadow rail minister Tanmanjeet Dhesi at the RMT-organised fringe meeting at the Labour Party conference, the union’s general secretary Mick Lynch said that “what we’ve got to do now is keep the top table in the conference under pressure, and not just on transport” (BBC News, 25 September).

The RMT press release reaffirmed the message that the fight will continue, stating that “the trade union movement will be on hand to make sure these Labour values are delivered for working people” (26 September).

But in the same way that independent union action is the vital ingredient in pressurising ‘the top table’ in workplace negotiations, shouldn’t ‘building the pressure’ on Starmer’s new New Labour party include an independent union-organised list of workers’ candidates in the next general election?

The former general secretary of Unite, Len McCluskey, said in an interview with GB News, that if he remains suspended Corbyn should stand independently of the Labour Party “without a shadow of a doubt… I think he should absolutely run again” (13 October).

And then, since the Labour Party conference, there is the Corbyn-supporting former MP Emma Dent Coad, debarred from the long list of potential candidates for her old seat of Kensington despite the backing of Unite. And Sam Tarry, deselected by the Blairites as the MP for Ilford South after his ousting from the shadow cabinet for appearing on a railworkers’ picket line.

An RMT predecessor union, the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS), was one of the principal founding organisations of the precursor of the Labour Party, the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), in 1900.

The aim of the new coalition – of trade unions and different socialist organisations – was to have political representatives under the collective control of workers, even as there was a constant tension between the Labour parliamentarians bowing to the pressure of capitalist interests and the party’s working class base.

In the first general election it contested, in October 1900, the LRC’s 15 candidates – including the general secretary of the ASRS – polled 63,304 votes, just a 1.8% share. But the process of creating a party of the working class was under way.

The Socialist Party believes that the establishment of a new mass workers’ party is an urgent necessity to ensure the political representation of the working class in the tumultuous events that lie ahead.

But an independent union-based election coalition would be a significant first step and the best way to prepare the movement for a Starmer government.