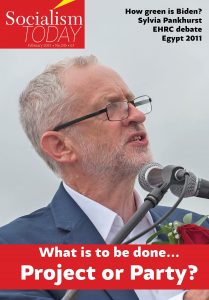

Jeremy Corbyn, just a year ago the left Labour leader and now suspended from sitting as a Labour MP, has launched a new Peace and Justice Project. HANNAH SELL analyses what it represents and whether it matches up to the tasks facing the workers’ movement.

Around 10,000 people attended the online launch of Jeremy Corbyn’s Project for Peace and Justice on January 17. Speakers – in addition to Jeremy Corbyn – included Len McCluskey, general secretary of the Unite trade union, Labour peer Christine Blower, and Yanis Varoufakis, the former finance minister of the Syriza government in Greece.

Did this represent a significant new development in British politics? It was taking place at a time when Britain’s Covid death rate is the highest recorded globally and 6.2 million people are being forced to rely on Universal Credit. Poverty is at its highest level for many decades.

As the working class faces this unprecedented crisis the priority of Labour leader Keir Starmer has been to show that – unlike Corbyn – he can be relied upon to act in the interests of the capitalist elite. He has spent the pandemic acting as a prop for the Tory government. Even when education trade unions forced the government into a humiliating U-turn on schools opening, Starmer refused to back the unions’ demands.

At the same time Starmer has presided over a systematic campaign to stamp out the embers of Corbynism. Less than a year after his resignation as Labour leader Corbyn is being forced to sit as an independent MP, having had the Labour whip removed on entirely spurious grounds. Now Richard Leonard, who was elected as Scottish Labour leader on a left ticket, has resigned, further undermining the already severely weakened forces of the Corbyn wing of Labour. It has been reported that pressure was exerted on Leonard to step down by Starmer, Angela Rayner (Labour’s deputy leader), and Labour general secretary David Evans, claiming it was necessary to secure the support of millionaire donors. Meanwhile swathes of Labour Party members and local party organisations have been suspended for speaking out against Corbyn’s suspension.

There is clearly an urgent burning need for the Labour and trade union left to come together and discuss out a strategy for how to fight back and to organise effectively in the interests of the working class. Unfortunately the launch of the Project for Peace and Justice bore no resemblance to the kind of event that is needed.

What was launched?

Zara Sultana, the Labour MP for Coventry South, was one of the few speakers to talk about the need for socialism and “a society run by and for the working class”. However, she – like all the speakers – did not address the question of how this could be achieved and ignored the elephant in the room that the party that the speakers based in Britain were all part of – Labour – is led by pro-capitalist politicians.

The only speaker based in Britain to make any reference to Corbyn’s suspension from the Parliamentary Labour Party was Len McCluskey, left general secretary of Unite, who supported Corbyn throughout his leadership. But while he correctly called for his reinstatement, he suggested that Jeremy had “changed the Labour Party forever” and that in the Labour leadership contest all “three candidates ran on socialist platforms, although we have to keep reminding Keir”.

This is when one of the candidates – Lisa Nandy (now shadow foreign secretary) – was part of the 2016 attempted coup against Corbyn. The victor, Starmer, has spent his time as leader systematically breaking from Corbyn’s policies. From largely backing the government’s approach on Covid, to whipping Labour MPs not to vote against the government’s Covert Human Intelligence Sources (Criminal Conduct) Bill – the ‘Spycops Bill’ – to failing to sign a letter to stop a Windrush deportation flight, Starmer’s every action from the smallest to the largest is designed to show that he does not have a socialist programme.

Any final shreds of doubt should have been obliterated by the recent statement of his shadow chancellor, Annelise Dodds, on the economy which was praised to the skies by the Financial Times, like all the capitalist press, as “backing away from the hard-left economic policies of Jeremy Corbyn”, using the word “responsible” 23 times in her speech.

No amount of ‘reminders’ will change Starmer’s direction. It was clear from the live feed of written comments that many participants fully understood this and had come to the launch hoping it would offer them a way forward.

Instead they heard general comments supporting ‘peace’, ‘justice’, ‘hope’ and, as Corbyn put it, “a more decent and just economy”. Nobody – including the pro-capitalist Starmerites – would be able to oppose these general aspirations. However, they were mostly not couched in terms that would resonate with working-class people suffering in the Covid crisis. And what these words actually mean, and how they were to be achieved, is largely absent from the material produced so far promoting the Project.

Is research the priority?

The Project’s mission statement declares that they “bring together academics and researchers, leaders and campaigners, and grassroots people and organisations to highlight injustices and solve problems together”. Research was also a dominant theme of the launch rally, with as much emphasis on ‘commissioning reports’, as on campaigning. Of course, the workers’ movement should highlight injustice, and research and discussion on policy development can play a useful role, provided it is linked to the real struggles of the working class. It does not, however, take research to work out the multiple crises – including health, poverty, employment and environmental – which the working class is facing now.

As Labour leader Corbyn put forward two manifestos ‘for the many not the few’ which gained nearly thirteen million votes in 2017 and over ten million in 2019. Corbyn still stands over these manifestos and the Covid crisis has driven home how correct many of their policies were. The case for free broadband, to give one example, is now unanswerable. That did not stop Starmer, when speaking to the Confederation of British Industry, refusing to commit to nationalising BT’s Openreach, only responding when questioned on it that Labour under his leadership would be “pro-business”. In the face of the Labour right’s abandonment of the 2019 manifesto ‘project’, a new ‘project’ that prioritises research to develop new policies, with extremely limited proposals for action, is unfortunately an avoidance of the burning question of what is to be done.

This is shown clearly by the ‘areas of work’ that Corbyn outlined in his speech. The four headlines were the green new deal, economic security, democratising society, and international justice. On the first Jeremy declared that, “Labour’s 2019 manifesto programme is arguably the most developed green agenda in the world”. But he then proposed that the Project for Peace and Justice will “commission new research, thinking, and policy that can be used by movements, communities and parties around the world to build a Global Green New Deal”.

Meanwhile no mention was made of the retreat from Labour’s manifesto pledge at the centre of its green new deal, to nationalise the six major energy supply companies and the water industry. In his Labour Party conference speech and since, Starmer has made no mention of these policies, while other shadow ministers – including Lisa Nandy – have publicly distanced themselves from them. Discussion with movements on the need to develop the 2019 manifesto further could obviously be positive – for example on the need to nationalise all of the major corporations and banks that dominate the economy in order to develop the only possible thoroughgoing green new deal, a socialist plan of production. However, avoiding a discussion on how to fight the retreat from previous steps forward is not helping to develop movements but disarming them.

Similarly in campaigning for economic security, Corbyn proposed that “our supporters – you – link up locally and address this economic emergency together. That may involve working with food banks, mutual aid groups, social organisations, or trade unions to support communities in this difficult period, whilst campaigning for a more decent and just economy”. No doubt many of those attending were already involved in supporting their communities by all those means and more, but how does proposing more of that lead to any decisive step forward in the struggle against inequality? Doesn’t the emphasis on food banks rather have the danger of retreating to appealing to socialists to concentrate on charity work rather than fighting to change society? Yet there are more than 120 Labour-led local authorities who have the power to introduce significant parts of the 2019 manifesto including, for example, introducing free school meals for all, increasing local authority workers’ pay, taking action in defence of private renters, and embarking on a mass council house building programme. This vital arena of struggle was not even mentioned during the entire event.

The proposals on democratising society drove home the same point. Corbyn rightly pointed out that “democracy is so much more than voting every four or five years – and sometimes with the choice of parties restricted to parties which fundamentally agree on most things”. He then highlighted the role of the billionaire-owned media and pledged that the Project for Peace and Justice would start by “taking on Rupert Murdoch” by urging supporters to sign a petition demanding a “parliamentary commission”. Yet nothing was said on how to change a situation where ‘parties fundamentally agree on things’ or even on making demands on the Labour leadership to back this incredibly modest petition.

Internationalism to strengthen – not evade – struggle at home

Unfortunately, the international character of the Project also increases its lack of a clear and effective purpose. Capitalism is a global system and the struggle for socialism has to be international. It is a starting point for all genuine socialists that workers in different countries need to be united in a common struggle against the capitalist classes of the world. In that sense all workers’ movement initiatives should have an international approach. And while we would not agree with Jeremy Corbyn on a number of international issues there is no doubt he has often taken a principled stance in opposing the crimes of British and US imperialism.

In an interview in the US-based Jacobin magazine in December 2020 on the launch of the Peace and Justice Project he gives an important illustration of this, explaining how – after the horrific Manchester arena terrorist bombing which took place during the 2017 general election – he faced enormous pressure not to make a statement that rightly completely condemned the barbaric attack, but also explained the consequences of US and British imperialism’s warmongering for the growth of terrorism. He explains “I was very strongly advised by many people not to do it: they said it would destroy the campaign, destroy our chances”. To his credit, however, he insisted and “a few hours later, YouGov produced a poll which showed 60 percent support for what I had said”.

In the general election just 17 days later Labour increased its vote by more than any party in a single election since 1945, including winning the support of more than a million people who had previously voted for the right-wing populists of UKIP. This is a concrete demonstration of how, despite the frenzied attacks from the capitalist press, a party which puts forward a programme in the interests of the working class majority, and is prepared to ‘say what is’, can win mass support.

The Jacobin interview, however, regrettably also reveals the weakness of the Project’s approach on internationalism. Neither capitalism nor the working class are mentioned at all, and much of the thrust is on the need to implement World Health Organisation (WHO) or United Nations edicts. On the pandemic, for example, Corbyn says “this crisis has revealed all of the inequalities in the world. And there’s going to be more of these kinds of novel viruses. So we’ve got to get real about the need for a World Health Program. The WHO have been talking for years about the need for access to universal health care. If the world can get together and give support to deal with Ebola, it could do the same with the coronavirus”.

Yet the fight against Ebola is not an example of the world ‘coming together’. It is true that, very belatedly – as a result of fearing the consequences if Ebola spread globally – drugs have been developed to treat it. Nonetheless, outbreaks are still taking place, and African countries have had to fight Ebola over many years with extremely weak health systems, often privatised under pressure from the global institutions of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. Sierra Leone which has suffered a number of outbreaks, for example, only has free healthcare for pregnant and breast-feeding women and children under five. It pays more in interest on debts to the World Bank and IMF than it spends on healthcare, education, or infrastructure.

While the World Health Organisation can often give better advice on health issues than individual capitalist governments, as has been the case during the Covid crisis, it is not truly an independent body but is made up of representatives of the governments of the world, and is dominated by the major imperialist powers. It is therefore part of the framework of global capitalism that codifies and enforces imperialist exploitation, and not a tool to help the working class and oppressed fight back against it.

The need to struggle for socialism internationally cannot be separated from the need to address the questions facing the working class in the country where you are based. Had a Jeremy Corbyn-led government been elected and implemented socialist policies that would have had a thousand times more effect on giving confidence to the working class globally to fight for decent healthcare than any numbers of pleas to governments to listen to World Health Organisation advice.

Similarly, had the left anti-austerity government elected in Greece in 2015 been prepared to defy the institutions of European and world capitalism, in order to implement a programme in the interests of the Greek working class, it would have had a transformative effect on the confidence and outlook of the working class across Europe. It unfortunately says something about the character of the Project that the final speaker at the launch event was the ex-Syriza finance minister Yanis Varoufakis who, rather than drawing out the lessons of the capitulation of the government of which he was part, chose to make abstract and incorrect points about the enemy today being not capitalism but “neo-feudalism”.

Heroism is not enough

Both in Corbyn’s speech to the January 17 rally and his interview with Jacobin, he emphasised that the movement shouldn’t be demoralised by short term setbacks, but should see the longer term positive legacy of struggles even if they are defeated. He gave as an example the legacy of Salvador Allende’s left-wing Popular Unity government elected in Chile in 1970 which was “overthrown by the CIA in conjunction with the Chilean military in a brutal coup. But his spirit lives on. Who remembers Pinochet with affection, who remembers Allende with affection? I think we know the answer”. This is undeniable. One of the many inspiring features of the mass movements that swept Chile in 2019-2020 was the way the slogans of the Popular Unity were adopted by the new generation more than forty years later.

Nonetheless, serious representatives of the working class have a duty at every stage to try to ensure the movements they lead are victorious rather than defeated, and if defeats are unavoidable that they are minimised as far as possible and the lessons are learnt for future battles. The Chilean masses suffered terribly as a result of the defeat. Thousands were murdered and the working class had to live through decades of brutal neo-liberal dictatorship. Yes Allende died a hero, but heroic defeat was not pre-ordained. Broad sections of the working class – who could see that a bloody coup was imminent – were demanding arms to defend the government which would have completely changed the course of events.

If Jeremy Corbyn retires tomorrow he will be remembered affectionately by the next generation of young people, many of whom first heard of socialism as a result of his leadership of the Labour Party. However, given his authority flowing from the last five years, he has the opportunity to be remembered for more than going down to heroic defeat at the hands of Starmer, but also for playing an important role in forging a mass political party for the working class and young people which could enormously strengthen their position for the struggles coming in the post-Covid era. Conversely if he, and as importantly the trade union leaders who support him, do not take steps in that direction, it can increase the period of time in which workers and young people have to face a choice of evils; between different brands of pro-capitalist politicians. This would inevitably increase confusion, and leave more room for right-populist forces to gain ground.

What kind of project is needed?

When Jeremy was Labour leader there was an opportunity to transform Labour into a mass workers’ party. As we have explained elsewhere, this was not done, allowing Starmer to take the leadership with the party machine, MPs, and structures ready and waiting to do his pro-capitalist will. Given that missed opportunity, a struggle for working-class political representation will not now succeed within the confines of the Labour Party. That is why the Socialist Party is arguing that we need to build a new mass workers’ party. It was recognition that the successful transformation of Labour is no longer posed that led some Corbyn-supporters to hope that the Project represented a step towards a new party outside of Labour.

Clearly, as it is currently envisaged, it does not. However, there are projects which Corbyn could grasp which would have a seismic effect in galvanising and enthusing the workers and young people who initially flocked to his banner, and scoring real blows against the pro-capitalist Starmerites. For example, the London Regional Council of the RMT transport workers’ union has agreed to consider standing or supporting an anti-cuts candidate for the Mayor of London. The right-wing Labour incumbent, Sadiq Khan, is threatening to pass on government cuts to London Transport via attacks on workers’ conditions and regressive charges for residents. If Jeremy Corbyn was to take up the London RMT’s suggestion and to stand on a left platform to be mayor of one of the biggest cities in the world, backed by a slate of socialist and trade unionists for the London Assembly, he could win. The ‘supplementary voting system’ also means that he could do so without giving space for the Tory candidate to come through the middle.

There is historical precedence for such a campaign. Back in 2000 Ken Livingstone broke with Labour and stood as an independent, winning the contest. Unfortunately, he used the position to re-gain acceptance by Blair’s New Labour, rather than to build a political force to represent working-class Londoners. On the contrary, he went onto call on workers to cross RMT picket lines. Corbyn, however, could use the position as a significant mobilising force against both the Tory government and today’s incarnation of New Labour.

Up until now, it has unfortunately not only been the Project but, it seems, all forces on the left that are studiously ignoring the need to fight on the electoral front – with the exception of the Socialist Party, the RMT, Chris Williamson’s Resist and others involved in the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC). Sometimes this is dressed up in radical phraseology about the struggle in the workplace or streets being the priority, and sometimes it takes the form of waiting for the problem of working class political representation to be solved ‘organically’.

However, for the majority of working class people disillusionment with pro-big business politicians is not the same as thinking it is possible to ignore politics altogether. On the contrary, most people recognise that having someone to vote for that will fight on your behalf in parliament or the council chamber is desirable. For example, for council workers whose jobs and conditions are under threat in the new era of post-Covid austerity, it will be clear that it will not help their struggle on the streets or in the workplaces to only have council candidates to vote for who are intent on continuing to threaten their jobs and conditions. No doubt some, especially those who are taking strike action to defend themselves, will ‘organically’ decide that their struggle will be strengthened if they stand themselves, and TUSC will be there to offer them a banner under which to do so. However, if Jeremy Corbyn and the left trade union leaders were to take steps to encourage them their numbers would be qualitatively swelled.

The six Labour-affiliated left-led trade unions that are rightly opposing Corbyn’s suspension, and seem to also be supporting the Project, need to urgently call a conference to discuss how best they can fight back against Starmerism, and for effective political representation for their members and for the wider working class. Representatives from outside of Labour, including the non-affiliated trade unions, the Socialist Party and others, should also be invited. If a conference agreed on even limited steps, such as freeing trade union branches to stand or back anti-cuts candidates in this year’s elections, and setting up a trade union group in parliament with Corbyn as its chair, it would do more to take the struggle forward in Britain than any amount of trying to convince Starmer to change direction or establishing projects to develop policy.

Jeremy Corbyn’s Jacobin interview also referenced Keir Hardie, one of the founders of the Labour Party, and how he, like Corbyn, had to withstand endless abuse from the capitalist media. Hardie was among those who, on the basis of their experience of bitter class struggles, drew the conclusion that workers in Britain could not just support the capitalist Liberal Party but had to find their own political voice. The establishment of the Labour Party was a prolonged process, with all kinds of setbacks and difficulties, but it represented an important step forward for the working class. Today, in an era of profound capitalist crisis, the working class needs its own voice more than ever before. A party, not a project, is the way forward.