The Black Lives Matter movement has reignited an ongoing discussion about whether or how reparations should be made for the horrors of slavery. To coincide with Black History Month we are publishing the following article by PAULA MITCHELL as a contribution towards that debate.

Karl Marx famously said that capitalism came into being “dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt”.

By this he meant “the discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the indigenous population of that continent, the beginnings of the conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve for the commercial hunting of black skins, are all things which characterise the dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation…”.

From the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, estimates vary but between ten and fifteen million Africans were kidnapped and crammed into merchant ships, to be enslaved in the Caribbean and southern states of America. The trade was begun by the Portuguese but by the seventeenth century Britain was at the heart of it. An estimated two million perished on the Middle Passage, dying in horrific conditions or thrown overboard. On arrival they were sold and sold again as commodities; families divided, and put to work on plantations; branded, raped, lynched and mutilated. The trade in slaves and in the commodities produced on the plantations was one of the key elements in the genesis of capitalism, and in particular enabled the growth of Britain as the world’s foremost capitalist economic power.

For hundreds of years, there have been calls for reparations for enslavement and its legacies on individuals and communities; for imperialism’s subsequent exploitation of Caribbean and African countries through colonialism and neo-colonialism; as well as for the material effects of the racist policies enacted in the US and European capitalist countries – racism that was consciously promoted in order to justify enslavement, and then developed as a vital tool of divide and rule of the emergent working class created by capitalism.

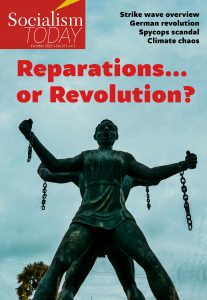

The call has revived in the 2020s since movements such as Black Lives Matter mobilised a new generation of especially young black people and raised their confidence to make demands, including reparations for slavery – as most graphically illustrated in the pulling down of the statue of Bristol enslaver Edward Colston.

Demands for reparations

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, long before slavery was abolished, demands were made in the US by former slaves and abolitionists for compensation to be paid to freed slaves. Reparations campaigning in Britain also dates back to the eighteenth century, and the ‘Sons of Africa’. The ‘Back to Africa’ movement of the 1920s and 1930s in the US, led by Marcus Garvey, was a movement involving thousands of Black Americans, demanding a version of reparations.

Reparations was also a demand of the civil rights movement in the US. Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a Dream’ speech 60 years ago famously declared: “We have come to our nation’s capital to cash a cheque”. He wrote in his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait: “No amount of gold could provide an adequate compensation for the exploitation and humiliation of the Negro in America down through the centuries… Yet a price can be placed upon unpaid wages… The payment should be in the form of a massive programme by the government of special, compensatory measures”.

The Black Panther Party’s ten-point programme included the demand for settling the “overdue debt” of slavery and racism. Malcolm X raised reparations in several speeches, for example in 1963: “All of that slave labour that was amassed in unpaid wages is due someone today. And you’re not giving us anything”.

Some modern-day campaigners in the US call for individual cash payments to the descendants of slaves; also, on an individual basis, student loan forgiveness, free tuition, housing grants and so on. Others make these demands for Black Americans in general. The first National Reparations Convention in Chicago called for Black people to receive free education, medical, legal and financial aid for 50 years, and for those choosing to leave America to receive a million dollars each. Other groups, such as the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, advocate for community rehabilitation rather than individual payments.

In 2014, ‘Caricom’ (Caribbean Community), made up of representatives of Caribbean governments, published a 10-point plan for reparations from ten European nations, including the UK. Among other things, it called for a formal apology from European governments, a repatriation programme for people of African descent in the Caribbean wishing to return to Africa, European investment in Caribbean health and education, and debt cancellation.

It is 30 years ago this year that the Africa Reparations Movement (ARM) UK was set up by MP Bernie Grant. It followed an international conference in Nigeria which called for “the international community to recognise that there is a unique and unprecedented moral debt owed to Afrikan peoples which has yet to be paid”. ARM UK’s demands included the return of religious and historic artefacts, debt cancellation, and investment in Africa and the Caribbean.

The current reparation campaign groups in the UK are particularly influenced by pan-Africanism, the idea of Africans taking back Africa. Campaigns such as the Global Afrikan Congress and the Stop Maangamizi Campaign (a Swahili term for African holocaust), come together under the banner of the International Social Movement for Afrikan Reparations, and have held annual protests in London for the last ten years. While strategies vary, there is a common idea of a more ‘holistic’ approach to reparations based on Africans taking power for themselves.

Failed compensation

So where should socialists stand on this centuries-long demand? There can be no doubt that the enslavement of millions of Africans is one of the worst crimes in human history, followed by decades of savage racism; and the impacts have been multiplied many times over through the exploitation of Africa and the Caribbean by western capitalist powers through colonialism and neo-colonialism.

In addition to the horrific human costs, the estimates of the value of stolen slave labour vary enormously. According to the Brookings Institute, in 1860, over $3 billion was the value assigned to the physical bodies of enslaved black Americans to be used as free labour. In 1861 the value placed on cotton produced by enslaved blacks was $250 million.

Lawsuits filed in New York in 2002 estimated that the wealth in the US created by the unpaid wages of slave labour was worth, at that stage, $1.5 trillion. The anthropologist Jason Hickel wrote in 2018 that, valued at the US minimum wage and with a “modest rate of interest”, the total reparations due for the estimated 222.5 billion hours of forced labour between 1619 and 1866 was a staggering $97 trillion. Earlier in 2023, a report launched at the University of the West Indies estimates the aggregate sum of total harm of enslavement at between $100-131 trillion, of which it said Britain owed 14 countries $24 trillion.

Added to these calculations are the injuries that followed. For example, in the American war of independence, the British proclaimed that all enslaved people who joined their ranks would be freed. After the war, defeated combatants went to Canada. On arrival in Ontario, the white families were given 250 acres of land each; Black families were given nothing.

Towards the end of the American civil war, Field Order 15 was issued, ordering that each freed black family should receive 40 acres, and many also a mule. It is estimated that around 40,000 freed slaves were thus settled. But after President Lincoln’s assassination, the order was reversed, and the land was returned to former slave owners. In fact, in many states the slaveowners were paid compensation. The ‘Compromise of 1877’, that meant the end of the ‘reconstruction’ period, saw many former slaves returned to the land as sharecroppers for the same slave owners, thus continuing to make their former owners vast amounts of wealth. The Economist magazine estimated in June 2020 that the equivalent of ‘40 acres and a mule’ today would be $160 billion.

In 1835 the British government took out one of the biggest loans in history to finance the slave compensation package under the Slavery Abolition Act. The £20 million borrowed, £300 billion in today’s money, was paid to slave owners for the loss of their human property. That debt was still being paid by the British taxpayer until 2015!

Incalculable costs

In 1896 the US Supreme Court ruled in favour of segregation. The ‘Jim Crow’ segregation laws in all public facilities, not least education, lasted until 1965. Racist housing policies, including ‘redlining’ to keep black and white areas separate and block black people from getting mortgages, contributed to the creation of ghettoes. There are many more effects than those directly attributed to overtly racist laws. For example, in Roosevelt’s 1930s New Deal, social security legislation excluded two professions – domestic and farm workers – from old age insurance and unemployment compensation, thus, according to the Brookings Institute, excluding 60% of blacks across the US and 75% in the southern states.

Over 150 years of post-slavery racist policies mean that, in 2020, the average white US family had roughly ten times the wealth of the average black family. According to The Economist, to equalise net wealth between black and white households would cost $8 trillion. And what price can be put on decades of discrimination in health and criminal justice – right up to the disproportionate deaths of black people during Covid and racist police killings of the 2020s.

These eye-watering amounts don’t include the wider effects of colonialism and neo-colonialism. For example, Caribbean campaigners argue that the health conditions faced by people in former British colonies – a ‘hypertension hotspot’ – are due to 300 years of being forced to produce and consume a diet based on sugar.

And what price can possibly be put on the ‘not one nail’ policy – the deliberate limits on industry in the colonies, in order to keep hold of all the means of profit creation, and prevent the development of rival capitalists – and of potentially powerful workers.

The Guardian revealed in July this year, for example, that the ‘Cort’ process, which allowed wrought iron to be mass produced for the first time, was first developed by mostly enslaved metallurgists in Jamaica, building on the experience of ironworking industries in their home countries of west Africa. In 1781, the British government forced the closure of the ironworks and shipped the machinery to Portsmouth. The innovation was one of the most important in the development of modern capitalism.

And, of course, the exploitation didn’t stop after independence. Perhaps the most well-known example is the fact that France extorted 90 million gold francs compensation from Haiti for its revolution, paid over 120 years to 1947.

Faced with mass movements of workers and poor people in Africa fighting for national and social liberation after the second world war, European powers were forced to negotiate settlements with nationalist movements and, where they could, installed compliant pro-capitalist leaders.

The coups taking place in west and central Africa today have highlighted some of the exploitative post-colonial arrangements. After independence, 14 French-speaking African countries signed 11 agreements with France. These agreements included ‘colonial debts’: newly independent states had to repay the ‘benefits of colonisation’. The African countries had to deposit their financial reserves with the Banque de France. France has the right of first refusal on the exploitation of raw materials, and French companies have priority in public procurement.

Debt, IMF bailout programmes with terms that demand privatisations and cutbacks, terms of trade, aid, as well as the direct exploitation by multinational companies, are all ways in which western imperialist powers have continued to super-exploit independent African countries. According to The Economist, the total stock of African external debt surpassed a trillion dollars in 2021, and the annual servicing costs exceeded $100 billion. Up to 20 African governments spend 20% or more of their annual revenue on servicing external debt.

Trying to express the legacy of enslavement and colonialism in money terms can help to underline the enormity of the issue. What is clear, however, is that the collective effect of enslavement, racism and imperialist exploitation over hundreds of years is impossible to put a price on. Given slavery’s role in the foundations of capitalism itself, how could it be anything other than incalculable?

Minimal progress

It is not enough for socialists to simply say, as some do, that the case is unanswerable, we must support demands for reparations. The key question that is left hanging by all of these facts, and all of the different reparations demands, is a simple, but huge, one. How?

The enormous sums calculated are immediately put into perspective by the annual gross domestic products (GDP) of the countries expected to pay them. US GDP in 2022 was $25.46 trillion. UK GDP in 2022 was $3 trillion. The University of the West Indies’ report that calls for the UK to pay $24 trillion in reparations proposes that this is paid over a ten-year period. That demand is clearly utopian.

Appeals to governments are understandable. The depth of hurt is palpable when, for example, a spokesperson for African Heritage Universe, calling for reparations in Canada, says: “We have been so thoroughly brutalised… We are left with no alternative but to ask, nay, implore, people of goodwill, who believe in justice, fairness and non-discrimination… to lobby your political representative, plus your religious leaders. Tell them to do the right thing”.

But appeals to ‘do the right thing’ have been made for centuries to little effect.

In 2021 an all-party parliamentary group for African reparations was established in Britain, chaired by Labour MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy, with the remit to “explore policy proposals on reparations and make recommendations to parliament on how to redress the legacies of African enslavement, colonialism and neo-colonialism today”.

This parliamentary group argues for the establishment of a parliamentary commission of inquiry for truth and reparatory justice. Its demands include debt cancellation, restitution of cultural property and human remains, public disclosure of the financial institutions involved in the enslaver compensation loan of 1835, and the restitution of the value of taxes paid by African heritage taxpayers in Britain to service that loan.

Campaigners take succour from recent small steps. For example, the descendants of the nineteenth century Liberal Party prime minister William Gladstone apologised in August this year – Gladstone not only owned 2,500 slaves and put down rebellions in a brutal manner, but championed the need for enslavers to be compensated, and himself received £106,000. His family is paying reparations through funding research in Guyana. Similarly, the descendants of the Trevelyan family.

The Labour MP Clive Lewis, vice-chair of the parliamentary committee, is pleased to report that King Charles “has made comments and apologies”. Lambeth and Bristol council have passed resolutions supporting reparations, as has the Green Party.

Campaigners point out that there have been reparations paid for some other groups. For example, they cite the fact that the US government has paid native Americans in land and dollars for being driven from their original lands.

Capitalist resistance

Yet the reality is that the trade in African lives and the subsequent global exploitation was and is a fundamental part of capitalism, and no capitalist power is going to either admit that or hand over vast sums of money in reparations. Reparations for slavery, racism and colonialism are of a different order from even the terrible wrongs inflicted on native Americans, for whom the amounts paid out by the US government are in any case wholly inadequate.

The examples of progress cited are tokens. The Gladstone family may be donating £100,000 but Gladstone’s wealth increased more than ten-fold due to exploitation of plantations, and the family today is worth millions.

Passing resolutions may have symbolic meaning, especially in a city like Bristol, built on the slave trade, but both Bristol and Lambeth councils, and the Green Party when in power, have carried out cuts and privatisations, which have attacked working-class people – including the people of African heritage who live in their cities. If you can’t stand up to the demands of the Tories for council cuts, how will you stand up to the interests of the capitalist class internationally?

In April this year, Bell Ribeiro-Addy asked Rishi Sunak in parliament whether he would make a “full and meaningful apology” and “commit to reparatory justice”. Sunak replied “No”.

Clearly having people of colour in a government operating in the interests of capitalism does not make a difference. How much progress was there on reparations in the US when Barack Obama was president? While Black and Asian people in power face racism, wealthy black capitalists benefit from the system overall and are not going to fundamentally challenge it.

In 2001, the United Nations did host a World Conference Against Racism in South Africa, with reparations on the agenda. But that, and the equation of Zionism with racism, caused the US and Israel to withdraw their delegations.

The capitalist class will only make concessions if they have no choice. The world crisis engulfing capitalism, economically, socially and politically, means sections of the capitalist elites might think it useful to encourage a few small concessions in order to abate pressure or win some short-term support.

But it is absolutely ruled out that the capitalist rulers will voluntarily hand over the vast sums of money requested, never mind relinquish hold of the multinational companies, the access and control of raw materials, the trading agreements, the globally strategic regions – all essential to maintaining not only the wealth of individual capitalists but the power and prestige of competing capitalist nations, especially in the current extremely unstable, multi-polar world.

They won’t even hand over previously agreed levels of aid! Boris Johnson cut aid from 0.7% of GDP to 0.5% during Covid, calling the Department for International Development a “giant cashpoint in the sky”. Further cuts have been made this year, including to east Africa, despite drought and rising food prices. The UN estimates that almost 72 million people in Africa require humanitarian aid this year.

More than a decade of savage austerity while the rich got richer, and decades of privatisation by both Tory and New Labour governments, has led to a situation of catastrophe for public services, a historic housing crisis and a million people using foodbanks. If the capitalists of Britain put their own enrichment and power before the living standards of ‘their own’ people, they are not going to take meaningful steps towards slavery reparations.

Working-class power

In the US, Bernie Sanders, when asked if he supported reparations, answered no, because they would be divisive. In a context of falling living standards and crumbling services, it is true that demands that appear to give more to some sections than others could stoke divisions, whatever the moral merit of those demands might be.

But that doesn’t mean not recognising or supporting calls for reparations, but developing a programme that is capable of uniting a movement that can win both real, meaningful reparation, and dramatically raise the living standards of working-class and poor people everywhere.

Capitalism’s “blood and dirt” was not only African slaves, or the inhuman oppression and exploitation of colonies. It was also the drawing together of big numbers of poor people from the countryside and small-scale production into the factories, mills and mines; long hours of dangerous toil by children, women and men, living in crammed, insanitary housing conditions, for meagre wages.

The development of mass wage labour, creating a majority in society whose only way to try to satisfy their basic needs against the interests of their bosses is collectively, meant the creation of what Marx called capitalism’s “grave diggers”: the working class.

The force in society that can not only challenge the bosses but also potentially take the wealth and power from the hands of the capitalist class is the working class, with its hands on the means of production, and its essential role in making society function. It has the potential to take power and run society democratically, in the interests of the vast majority, if organised and armed with a programme to do so.

It is therefore essential to develop a programme of anti-racist, anti-capitalist demands that, while recognising the just demands to repair the horrific and centuries-long wrongs of enslavement, colonialism and neo-colonialism, is able to unite all sections of the working class in a fight against the capitalist system that perpetrated and perpetuates those wrongs. That requires demands for jobs, homes, services, pay rises for all; to nationalise the main parts of the economy, and to democratically plan for the needs of all society. In other words, a socialist programme.

Such a programme is also necessary to draw class lines within the campaigns for reparations. If the solution for reparations is, for example, individual payouts to descendants of slaves, what does that mean in reality? Why should a wealthy US senator who happens to be descended from a slave get a payout, while poor black American workers who are descended from more recent immigrants get nothing?

Similarly, if former colonial powers or enslaving nations are to pay money over to Caribbean or African governments, who gets the money? Capitalist governments in hock to imperialism? Millionaire politicians in walled compounds with private armies to protect themselves from their own populations? NGOs and charities?

That raises the need also for democratic demands: who decides? It should be democratically elected and accountable representatives of the working class, of communities and trade unions that decide what and how measures are taken.

Struggle in Africa

Taking control not just of currently existing wealth but of wealth-creation – ie the factories, banks and land – could utterly transform the situation for people of African heritage across the Americas and Europe, and in Africa itself.

The Stop the Maangamizi campaign rightly rejects the idea that the system tells people of African heritage what is appropriate for reparations. It rejects “the neo-colonial puppet leaders”. It says the leaders of Caribbean nations in Caricom “don’t speak for us”. It argues that African people need to take power for themselves.

Leading reparations author and activist Esther Stanford Xosie argues that pan-African movements need to “compel the stopping of neo-colonialism… combining our collective power to ensuring the redistribution of wealth, and ushering in a new international political and economic order”.

Who can do that in Africa? Not the ‘neo-colonial puppet leaders’. But not the African business leaders either, who don’t want redistribution of wealth any more than their counterparts in the west. While there is support among sections of the population for the current wave of coups in west and central Africa on the basis that they appear to stand up to imperialism, undemocratic military leaders who want to carve out their own areas of influence and access to wealth will not satisfy even the most basic demands of the masses of struggling people.

It is a mass movement of the working class and poor in Africa which has the motivation and the potential power to overthrow the capitalist governments in their own countries, and link up across borders. Appeals to ‘Africans’ to take power would have little resonance with African workers who have been subject to grinding poverty and military brutality for generations by different African leaders. But a class programme to take ownership and democratic control of the vast wealth in the interests of the billions not the billionaires would be entirely different.

Mass movements take place all the time. Particularly if organised on a class basis, ie with trade unions and a working-class party armed with a socialist programme, the working class could take power initially in any number of African countries. If military coups are infectious, imagine the contagion of workers throwing out the rich. The working class taking power in the capitalist west would be able to give support to movements in Africa and the Caribbean to similarly overthrow their corrupt regimes.

Socialism would release huge potential. The takeover of the multinational companies and financial institutions could immediately guarantee wages, prices, and workers’ control in those companies. It would open up the possibility of international planning of investment, technology and skills, as well as mass public investment in homes, education, health and living standards, including for people of African heritage and white workers in the west. Over time, a society run in that way would be able to overcome the centuries-old divisions of class society, including racism.

Martin Luther King said, in 1964: “Not all the wealth of this affluent society could meet the bill”. He was right – about capitalism. But overthrowing capitalism and replacing it with democratic socialism would, as Marx suggested, just be the beginning of the real flourishing of humanity. It could meet the bill many times over.