Short of a Lazarus-style miracle Tory resurrection the Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer will be installed in Downing Street on July 5, ushering in a turbulent new period in Britain.

Amidst the driving rain and whirr of overhead TV helicopters accompanying prime minister Rishi Sunak’s hapless live general election announcement speech, the strains of the 1997 ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ New Labour anthem could be heard, broadcast by nearby protesters. A Tory wipeout of similar proportions is entirely possible this time too. But any hopes that a Starmer-led government can replicate the relative stability of the first Tony Blair administration will not be fulfilled. “They may ring their bells now”, said the first de facto prime minister of Britain, Sir Robert Walpole – although the prevailing sentiment today is more one of disillusionment with all ‘politicians’ – but “before long they will be wringing their hands”.

Starmer, it is true, has managed to restore the thoroughly capitalist character of Labour established by Blair’s 1990s transformation of the party into New Labour, another ‘normal’ capitalist party in the mould of the US Democrats. Blair reconstituted what had been since its formation a ‘bourgeois workers’ party’ – a leadership at the top reflecting the demands of capitalism but with a broad socialistic ideological foundation and a structure through which workers could move to pursue their interests. The New Labour ‘project’ to end class-based politics was hailed by none other than the former Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who claimed it as her greatest achievement.

Jeremy Corbyn’s unexpected Labour leadership election victory after the 2015 general election was based on those outside the party rather than within; the £3 ‘registered supporters’ and union ‘individual affiliated members’ who gave him his initial majority in 2015, in an electoral innovation for internal party selections that has since been abandoned under Starmer. Corbyn’s win threatened to overturn the two-decade long ‘political settlement’ that had been established. The ruling class were shaken at the possibility that the element of independent working class political representation that had existed within the Labour Party in the past could now be restored.

But Corbyn and his leadership team equivocated, seeking to reconcile the agents of capitalism within Labour rather than complete its transformation into a democratic workers’ party. Now, nine years later, with the policies and personnel of the Corbyn insurgency ruthlessly expunged, Starmer can confidently say that ‘my party has changed’ – back to Blairism. But that is certainly no guarantee of a stable period of capitalist rule, however big the parliamentary majority.

Blair came to power in May 1997 against the benign backdrop – for capitalism not the working class – of the broad shift in the balance of class forces that characterised the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Stalinist states of Russia and Eastern Europe from the late 1980s. The seeming triumph of capitalism as the only viable system of organising society affected the confidence and organisation – and fighting capacity – of the working class. The UK economy, meanwhile, had recovered from the recession of 1990-1992 to hit GDP growth of 4.9% in 1997. Even comparatively feeble British capitalism was underpinned throughout this period by US-dictated globalisation forcing open new markets and sources of cheap labour, until the crash of 2007-2009.

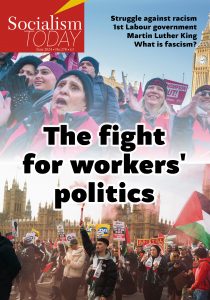

But that economic and political era is over, internationally and in Britain too – not least in Britain in the revival of working-class struggle of the last two years and now the still ongoing movement against the war on Gaza. This is not 1997. And while the attempt to re-establish working class political representation within Labour has been repelled, the prospects for its development outside the confines of the party framework are far greater than they were in the first decade or so of the post-Stalinist era.

Yet the election will also show how far, politically and organisationally, there still is to go.

Possibility of a parliamentary bloc

With Jeremy Corbyn standing against a Labour opponent in his Islington North constituency, heading a list of other Socialist Campaign Group ex-Labour MPs contesting seats on July 4, there is a possibility that a small bloc of MPs could be elected that could constitute the beginnings of a workers’ parliamentary opposition to Starmer’s pro-capitalist government in the struggles to come.

Corbyn will be joined on ballot papers by Claudia Webbe in Leicester East and the former MP Emma Dent Coad in Kensington & Bayswater; and, potentially still, by Diane Abbott in Hackney North & Stoke Newington. The former African National Congress (ANC) member of the South African parliament Andrew Feinstein is standing against Keir Starmer in his Holborn & St Pancras seat, as one of a number of candidates motivated to stand, in particular, in protest at Labour’s acquiescence with the slaughter in Gaza.

But the fact that they are standing as ‘Independents’ in itself is a sign of how unprepared the left in the organised workers’ movement has been in the past period – politically and organisationally – to seize the opportunities before it. It is over three years since Jeremy was suspended from the parliamentary Labour Party, during which period there has been no realistic prospect of his reinstatement. The Labour lefts and the left-wing trade union leaders could by now have established a far clearer working class and socialist banner to contest elections than ‘Independent’.

There have been, after all, independent MPs elected in (localised) ‘popular revolts’ even in recent history, who have not provided an alternative to the capitalist establishment politicians. In 1997 the former BBC reporter Martin Bell – ‘the man in the white suit’ – was elected as an independent in a protest against Tory sleaze; and in 2001 the hospital consultant Richard Taylor became the MP for Wyre Forest, re-elected in 2005. Independents actually form the fourth largest group in UK local government, with over 1,600 councillors in England alone, acting no differently from other capitalist politicians where they control authorities. And when eight Blairite MPs left the Labour Party to try and sabotage Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership early in 2019, joining with a group of ‘moderate’ Tories, they called themselves the ‘Independent Group’, hiding with that label whose capitalist interests they were really serving.

It is possible, of course, that some of those standing as ‘progressive independents’ this time would not have been prepared to adopt a working class or socialist ‘identifier’ on the ballot paper, no matter how authoritative it was. But would that have weakened the workers’ movement and its understanding of and confidence in its own power? Not at all. On the contrary, not adopting the movement’s banner would have been a political choice made by individual independent candidates, making it clearer to all the answer to the question – vital for the future battles to come – who are they independent from? The capitalist rulers of society – or the working class?

The same consideration applies to those using the Green Party label, whatever their personal merits. The Greens as a party do not have a socialist ideology, which leaves them with no anchor to resist the pressure to adapt to policies that reflect the interests of the capitalist system. They are not a party rooted in or emanating from the organised working class, which would also act as a counter-pressure on them to resist the demands of capitalism. At a simple level, if a trade union, for example, was to support the Green Party, it would have no means of exercising its weight as a collective organisation of workers within the party structures or subject the action of party representatives to the union’s democratic procedures of accountability.

Some individual Greens – or, indeed, individual left-wing MPs who manage to get back into parliament on the Labour ticket on July 4 – may play a role in creating a new vehicle for working class political representation. But neither the Green Party as an institution nor Starmer’s Labour are a route to a new, mass democratic workers’ party.

Many of the independent candidates stress their own personal integrity, contrasting it to the widescale perception of the capitalist establishment politicians as being in it for themselves. But that is not the same as being a workers’ representative. Andrew Feinstein, for example, resigned as an ANC MP in 2001 in protest at its refusal to investigate a potentially corrupt arms deal. But even that commendable personal stance is not the same as, for example, the accountability imposed upon the MPs of our predecessor organisation Militant – Terry Fields, Pat Wall and Dave Nellist – as workers’ MPs on a worker’s wage, only taking the wage of a skilled worker in their time in parliament. Their parliamentary accounts, including their wages, were presented to their constituency Labour Party general management committees (GMCs), composed of delegates from trade union branches, Women’s Sections, Young Socialists, and local ward parties, and open to those delegates’ inspection. Which working-class organisations will the independent candidates be accountable to?

Nevertheless, however heterogenous it may be, the possibility of achieving a parliamentary pole of opposition to Starmer’s capitalist government must be seized by the workers’ movement as a step towards a new mass workers’ party. The election of two MPs under the umbrella of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900 was also a modest step (with one of the MPs elected, Richard Bell, subsequently defecting back to the Liberals), but it was an important one towards the formation of the Labour Party in 1906.

The Workers Party

The same broad issue of accountability to organisations of the working class also applies to the Workers Party of Britain led by George Galloway, who will hope to be re-elected in the Rochdale seat he won in the February 29 by-election.

Despite serious differences with George Galloway Socialism Today would welcome his re-election now as we welcomed his victory then, arguing at the time that the Workers Party could become an important “lever to speed up the development of a new party” – although only, we warned, “on the basis of collaboration with others in the trade union and socialist movement” marching on the same path. (Editorial, Socialism Today No.275, March 2024)

Unfortunately, although the Workers Party continues to sit as observers on the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) steering committee and has withdrawn prospective candidates in some seats, in most others it has not done so – in pursuit of its own narrower aim to qualify for ‘Short Money’ state funding by winning 150,000 votes across the country. This approach has included putting up candidates, who have no traceable record in the local workers’ movement, against the Socialist Campaign Group members John McDonnell, Aspana Begum, and Zarah Sultana.

Standing or not standing against left Labour MPs is not a principle. The Socialist Campaign Group itself has seen the formation of a ‘New Left’ group within it, including Clive Lewis and Nadia Whittome, who want “distance from the ‘toxic legacy’ of Corbyn”, as reported by the New Statesman. (26 February 2024) But this new group does not include John McDonnell, Apsana Begum and Zarah Sultana; who it is not excluded, under the pressure of the movement, could become part of a workers’ opposition bloc in the next parliament if they are re-elected.

At least there should have been a discussion with the left-wing unions backing these MPs – John McDonnell has been a long-standing member of the RMT transport workers’ union parliamentary group, for example – and workers’ organisations locally to discuss whether or not a candidate should have been stood against them. When the RMT had official representation on the TUSC steering committee it was able to use its position to block a (small) number of prospective candidates who had applied to stand against RMT-sponsored candidates. That is inherent in TUSC’s inclusive federal structure which not only allows trade unions to have a decisive say but enables socialists from different organisations to co-operate as equals under one ‘umbrella’. But the Workers Party is not organised like that.

Some left-wing figures in the trade union movement have criticised the approach of the Workers Party to treat all Labour MPs without distinction as ‘fair game’. But ultimately it is not the Workers Party, nor the individuals who have come forward with the best intentions to stand as candidates for them or as independents, who are responsible for the current situation. In the absence of an authoritative working class-based alternative all types of forces will fill the vacuum – albeit partially, and temporarily – sometimes contributing to the process of the formation of a new mass workers’ party, sometimes not. But that only places a greater onus on authoritative workers’ leaders and organisations to act. The working-class movement did not have to be in the position that it is now of having no cohered electoral alternative – a new workers’ party or at least an organised workers’ list – in place for July 4.

No more procrastination

Following the suspension of Jeremy Corbyn in November 2020, Socialism Today warned that “the biggest danger in this situation is that, disillusioned with the onward march of Starmer’s counter-revolution, the forces of Corbynism will dissipate” if the response remained as a fight “prescribed by the weighted rules and procedures of the Labour Party and the capitalist courts”, which was the strategy being advanced by the Labour and trade union left. (How Far Can The Starmer Counter-Revolution Go?, in Socialism Today No.244, December-January 2020/2021)

Instead, we argued, “the Labour lefts could play a pioneering role. With the left-led trade unions at the core of a fightback, they could turn the battle over Corbyn’s suspension into a movement to help create a new mass vehicle for the political representation of the working class. That is the broad historic task that it is necessary to begin now”. The workers’ movement was in a different situation compared to that in the 1990s “after the experience of 13 years of Blairism in power and eleven years of austerity following the financial crash of 2007-08”, we concluded. “If even ten or twenty left Labour MPs and the left-led unions seized the moment – with the support probably of at least a group of councillors in most areas – they could transform the political situation”. The Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU) disaffiliated from Labour soon after, ending 119 years of membership, but no other steps were taken by other unions.

Further opportunities arose for the workers’ movement to put itself at the head of the deep disillusionment with the capitalist politicians as the mass strike wave against the cost-of-living crisis developed in 2022. As the RMT general secretary Mick Lynch correctly said at the union’s 2023 annual general meeting (conference), it “revived the trade union movement, putting our values and our policies back into the mainstream in this country”. The working class and its unions were back as a leading force in society, a ‘subjective factor’ able to shape events. But not on the electoral terrain, he argued! The conference agreed to support Jeremy Corbyn if he stood as an independent, on a motion initiated by Socialist Party members of the union, but Mick Lynch opposed the idea of organising a wider working-class challenge.

Most recently opposition to the war on Gaza led to an 18% drop in Labour’s vote in May’s local elections in areas where more than a fifth of the population identified as Muslim, according to a survey of 930 wards conducted by Southampton University researchers. As Isai Marijela’s article on page six argues, Britain’s Black and Asian population is overwhelmingly working class – bearing the brunt of austerity as well as ingrained racism – and a major shift from Labour amongst an important section of workers from a Muslim background is extremely significant. But only if the organised workers’ movement points a way forward, creating a new mass workers’ party and fighting for the socialist programme needed to transform society.

The election has been called and already a leak has come of warnings from Starmer’s advisors of the ‘shit list’ of council and university funding crises and NHS and school pay battles that his government will potentially face in its first few weeks. The opportunities in this election must be seized – but above all there should be no more procrastination on the need for a new mass party of the working class to politically represent its interests in the events that lie ahead.