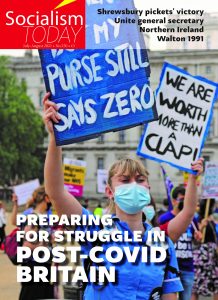

Far from an era of sustained economic upswing, social peace and a Tory ascendency opening up for post-Covid Britain, the prospects ahead are for heightened class conflict and turbulent political times, argues HANNAH SELL.

The last fifteen months have been unprecedented in the history of capitalism. In Britain a total failure to deal effectively with Covid in its early stages left the government struggling to cope with a developing health catastrophe, via belated and inadequate lockdowns, leading to the deepest economic recession in 300 years. As in other major economies, only levels of state aid unprecedented outside of wartime prevented worse disaster.

The population has been through a deeply traumatic experience. Almost 130,000 have died of Covid, with many more suffering long term health problems. Over six million were claiming Universal Credit in May 2021. Eleven and a half million have been furloughed at some point, usually resulting in a 20% pay cut. Despite a formal ban on evictions, 130,000 families have lost their homes so far.

Now, albeit with delays and reverses, Britain appears to be edging towards its post-pandemic future. What will that hold? According to The Times, Tory prime minister Boris Johnson is eyeing up “a decade in power” following his party’s victory in the Hartlepool by-election and continued poll lead. Is that possible? After all, the UK’s economy is currently reported to be growing at the fastest rate since the second world war. Could a post-Covid Britain feature strong economic growth, ‘levelling up’ for significant sections of the working class, and a stable majority for a Johnson-led Tory government?

Such a scenario is completely ruled out. It is only the weakness of the Labour ‘opposition’ that has given an illusion of Tory strength. Defeat in the Chesham and Amersham by-election, where the Tory vote slumped to 36% – having previously never been less than 50% – is a first indication of their troubles ahead. However, it also highlighted Labour’s crisis, with their worst ever by-election result of 622 votes, 1.6% (compared to coming second with 11,374 votes in 2017 and over 7,000 votes in 2019), a vivid illustration of the total lack of electoral appeal of Starmer’s pro-capitalist Labour. This is now a party that suspends from membership a representative on its national executive committee from Unite – its biggest union affiliate – while welcoming with open arms the previous Tory speaker, John Bercow.

Elections have always represented a ‘snapshot’, a moment in time, but today that is truer than ever before. The social base of the major parties has been deeply eroded over recent decades, making commonplace sudden shifts, like the voters of Chesham reviving the half-dead Liberal Democrats to protest against the Tories. In the next period it is possible that both the Tory and Labour Parties could shatter under the impact of events.

A world in turmoil

Britain’s future will not be one of stability but of heightened class conflict, flowing from the crisis of world, and specifically of British, capitalism. Globally, far from feeling confident, most serious capitalist commentators are looking at the future with extreme trepidation. One factor is that they have no idea what the consequences will be of shutting down huge swathes of the world economy for fifteen months, keeping parts on life support via enormous state aid measures, an experiment that has never been made before.

Last year the world economy shrunk by 3.5%. Now it is resurging and the OECD predicts it will grow by 5.8% in 2021. This could, of course, be cut across by new waves of Covid. However, if the OECD’s predictions are correct, it expects the world economy to be $3 trillion smaller by the end of 2022 than the pre-Covid trend, a contraction “about the size of the whole French economy”.

In addition it is already clear that the recovery will be ‘K’ shaped, with winners and losers. Increased conflicts are inevitable between different sections of the capitalists, and also between classes, about who will emerge strengthened into the post-pandemic world.

There are will also be winners and losers between nation states. While China and the US are recovering more strongly, Europe is estimated by the OECD to be lagging a year behind. Worst of all is the situation for the neo-colonial world. Britain, however, is predicted to be among the worst affected of the economically-developed countries. The OECD estimated at the end of May that Britain’s economy will suffer the deepest scarring of the G7 countries, with its long term growth rate likely to be 0.5% a year lower than pre-pandemic predictions.

Another reason for the capitalists’ trepidation is that the pandemic is not yet over. In countries with high vaccination levels it is hoped Covid will soon become a manageable endemic ‘background’ disease, provided the vaccines prove effective against new variants. Globally, however, only 17% of adults have currently been fully vaccinated. For Africa the figure is 1.5%. The pledges of the G7 are a drop in the ocean compared to what is needed to inoculate the world. In the meantime, alongside untold misery whenever there are surges in the neo-colonial countries, global travel restrictions, with ongoing economic consequences, remain inevitable.

Finally, and most importantly, the pandemic did not develop in a world with a healthy vibrant economic system, but in an era of deeply-crisis ridden ailing capitalism, which had not overcome any of the underlying faults that created the 2008 Great Recession and was already heading towards a new phase of crisis when the pandemic hit. Before the pandemic levels of debt in the world economy had reached gigantic levels. Back in 2019 the IMF estimated that the levels of debt in eight major economies, including Britain, was such that a recession half as deep as 2007-08 would lead to 40% of businesses facing bankruptcy.

In the Covid crisis, far deeper than 2007-08, the capitalist classes of all the major powers had no choice but to try and prevent that scenario, and to put a floor under the crisis, with huge stimulus packages and ultra-low interest rates. The IMF estimates that without the stimulus packages the consequences would have been three times as bad. However the actions taken have also stored up problems, exacerbating all the pre-existing underlying crises of capitalism. By the end of 2020 total global debt had reached a staggering $281 trillion, more than 355% of world GDP, and it has climbed further since. Governments, companies and individuals are all highly indebted.

At the same time the cheap money sloshing around the world economy has further inflated the speculative bubbles on the world’s stock and financial markets. In the US the stock markets price-to-earnings ratio, cyclically adjusted, is now the highest since both 1929 prior to the Wall Street crash and the dot.com bubble at the start of this century. The US Federal Reserve can see that the party has reached fever pitch, and are frightened of the likely scale of the hangover, but also want to avoid triggering the come down by turning off the taps too soon.

Differences with the Great Recession

US capitalism, still the strongest power on the planet, has learned some lessons from the response to the 2008 crisis, where the huge sums pumped into the economy via quantitative easing (QE) and other measures amounted to ‘socialism for the rich’. It is a condemnation of 21st century capitalism that these huge sums did not result in an increase in investment in science and productive technique. On the contrary Capex (capital investment) remained at a historically low level, with the exception of China. The driving force of capitalism is not meeting social need but maximising profits. For decades the capitalists have found it increasingly difficult to find profitable fields in production as in many sectors there is overcapacity compared to money-backed demand. QE therefore fed the further growth of speculative bubbles and the already dominant finance sector.

The Biden presidency hopes to change this, and to kick start US economic growth, by increasing the spending power of the US working class. Hence the Biden presidency has also delivered some cash payments into workers’ pockets. While the stimulus is undoubtedly fuelling growth in the US economy, as far as increasing the longer term spending power of the US working class is concerned, the measures agreed are very limited. However, Biden is attempting, via his infrastructure and other projects, to take actions which could potentially have some longer term effects. If they were all passed and implemented there would be an element of the 1930s New Deal although on a smaller scale. The New Deal was equivalent to about 40% of the US economy, compared to 28% for Biden’s proposals, which currently seem unlikely to make it through Congress in their entirety.

Biden is also desperately trying to reassert the dominance of US imperialism and to form a coalition aimed at blocking the rise of China. However, the G7 summit, which agreed an extremely limited statement on China, is an indication of the difficulties he faces. Biden’s efforts will not prevent the long term decline of US imperialism, and the continued development of an unstable multipolar world.

This has the effect of destabilising every aspect of capitalist relations. For example, there is currently a debate raging between different wings of the capitalists about whether there is a danger of inflation taking hold. Short term there has been a spike in inflation. In Britain, for example, industry’s raw material and fuel costs rose by 10.7% in the 12 months to May, the biggest annual increase for almost ten years. Clearly central factors are the surge in demand as the economy reopens, and the inevitable bottle necks and supply shortages caused by the global lockdown, as well as the increased cost of labour in ‘covid safe’ economic activity.

However, in the abstract a longer term development of moderate inflation could be positive for capitalism because it would decrease the size of historic debts, as happened in the post-war period. However, that was achieved by the complete dominance of the US over the capitalist world, allowing a stable global financial framework; the Bretton Woods agreement. In today’s world of increasing tension and conflict between nation states rising inflation would be far more dangerous. In addition the unprecedented levels of debt – corporate and private as well as government – means that even small increases in interest rates could have devastating consequences.

Brexit Britain

In this chaotic world, British capitalism is a weakening power with limited room to manoeuvre. As in the US, here too the austerity of the post-2010 years – which resulted in government spending falling from £6,410 per person per year in 2010 to £5,370 per head in 2017 – has been jettisoned; at least in words. Here, however, words are not being followed up by measures equivalent to even the limited actions of the US government.

As the furlough scheme finishes at the end of September, inevitably leading to a hike in unemployment, the government is also planning to slash Universal Credit by £20 a week, with destitution levels predicted to double. Local authorities, having had their funding cut by an average of a third over the last decade, are in dire straits. Twenty-five councils are reported to be close to technical bankruptcy and the overwhelming majority of local authorities – 94% – are planning further cuts to jobs and services in the coming year.

Public sector workers, including in the NHS, face a real terms pay cut. The government’s initial 1% pay offer for health workers is an indication of their intention to try and face down the trade unions. This is the real agenda behind their ‘Great British Rail’ announcement. The changes being proposed, the biggest since the Tories initiated privatisation of British Rail in 1994, are a confession of the bankruptcy of the profit-driven rail system. Nonetheless, they are not a move to renationalise, but rather to leave the private Train Operating Companies in place, guaranteeing their income regardless of ticket sales, and therefore freeing them up to try and take on and defeat the rail unions, and in particular the most militant of them, the RMT. A similar battle is being prepared by the government, with the compliance of Sadiq Khan, on London Underground. These facts alone are an indication of the vicious anti-working class character of this Tory government, and of the scale of the class battles ahead.

At the same time there are more than five million patients on NHS waiting lists, big pressure to spend more than the puny £1.5 billion so far pledged to fund education catch up, an acute social care crisis, and a massive backlog in the court system. There is no prospect of the government spending the sums necessary to resolve even these immediate crises.

The dangers for British capitalism in borrowing for continued large scale state intervention are far greater than for the US. The UK government borrowed £303 billion last year, unprecedented outside of wartime and pushing the national debt over 100% of annual GDP, the highest since the early 1960s. This is still below France (113%) and the US (127%) but that does not mean there are no dangers if debt levels continue to soar.

British capitalism, already in decline, has been further weakened by the consequences of Johnson’s Brexit deal. Johnson is a ‘pound land’ Trump, a right-wing populist who recklessly endangers the interests of British capitalism. The Socialist Party opposes the EU, which is a bosses’ club driven by maximising the profits of the capitalist elites across the continent. We backed a leave vote in the binary choice referendum on the UK’s EU membership in 2016 from the standpoint of working class socialist internationalism. However, we do not give the slightest support to Johnson’s Brexit deal.

For entirely different reasons, the big majority of Britain’s capitalist class also opposed it because they thought it would be destabilising, and would hit them in the profits. They were right! The extent has been partially disguised by Covid, but will become clearer in the next period. Exports to the EU by Britain’s biggest manufacturing sector – the food and drink industry – dropped by 46% in the first quarter of this year compared to a year ago, with industry bodies blaming the effects of Brexit. The City of London, while still a global financial centre, lost £2.3 trillion worth of trading in derivatives alone.

Nor is Brexit a finished process. On the contrary, British capitalism faces a period of endless negotiations over trading arrangements with the EU. Johnson’s reckless determination to pursue a capitalist hard Brexit deal has created intractable problems in Northern Ireland, which are ramping up sectarian tensions. They also – if the Tory government again unilaterally delays the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol, for example – risk tariffs being added to the problems faced by British companies trading in Europe. One of the consequences would be to increase the heat on the growing campaign for a new independence referendum in Scotland. In such a situation a run on sterling, and consequent difficulties in servicing UK government debt, could not be ruled out.

The capitalist class are horrified at the avalanche of problems heading towards the government, and Johnson’s reckless approach to them. The series of leaks by unnamed ministers pressurising Johnson to consult his cabinet before making off the cuff announcements, including anonymous jokes that ‘maybe he can get someone to set up a trust’ to pay for his impromptu spending pledges (referring to his attempted scam to get his luxurious renovation of his Downing Street flat paid for) are an indication of a growing desperation to bring him under control.

As the ephemeral ‘vaccine bounce’ which helped him in May’s local elections fades, and his appearance of being electorally successful with it, it is possible that the Tories could move to ditch him in relatively short order. The vast majority of the small section of workers who have lent the Tories their votes in the hope of ‘getting Brexit done’ will not become loyal Tory voters, but instead be furious at Johnson for delivering a diet of continued low pay and super-exploitation. If there is not a mass workers’ party with a socialist programme able to appeal to them, the space will be created for new right-wing populist parties. It is ruled out, however, that a new stable Tory Party will be the end product.

The looming struggles

Nor is there any prospect for sustained healthy economic growth. The stronger the current recovery the better, as it will give workers more confidence to fight to recover what they have lost during the pandemic. Capitalist commentators have compared the current growth to two periods, both short-lived: first to the rapid post-first world war recovery in 1919, and second to the 1972 ‘Barber boom’. Both were in periods of capitalist crisis, and both were preludes to gigantic class battles. The first culminated in the magnificent 1926 general strike and the second saw a near general strike developing from below in response to the 1972 jailing of the dockworkers. Class battles on a similar scale are ahead again.

For the working class it will not be a question of whether struggle takes place, but of whether it is spasmodic and spontaneous, or if it can be harnessed into an organised and effective movement. The workers’ movement went into the pandemic in a state of disarray. In the wake of the betrayal of the 2011 public sector pensions struggle many of even the left trade union leaders had no confidence that struggle was possible. This was reflected in their pitiful failure to fight against the Tories latest repressive anti-union laws. Especially given the low ebb of trade union struggle, the election of Corbyn as Labour leader seemed to offer a way forward. His final defeat, coinciding with the start of the pandemic, fuelled the completely mistaken initial response to Covid from the big majority of national trade union leaders, who came behind the government in a show of ‘national unity’.

However, despite the vacuum at the top, there has been a marked increase in trade union action even during the pandemic, particularly among sections of workers who have been on the frontline. Trade union membership has increased for the fourth year in a row to 6.6 million, as a result of a 224,000 increase in membership in the public sector. Unsurprisingly, almost half of the new members were employed in education where workers have been fighting heroic battles over health and safety throughout the pandemic, including forcing Johnson into a screeching U-turn at the start of this year. The election of five Socialist Party members to the executive of the largest teachers’ union, the NEU, is a reflection of the increased combativity of teachers, as is the winning of a majority for the left on the national executive of Unison, the biggest public sector union.

While public sector trade union density is now 50%, it is only 13% in the private sector. Nonetheless, there too there has been an increase in determined trade union resistance to employers’ attacks. The pandemic has thrown all aspects of life and work into the air, and employers are fighting hard to make sure that, as the cards fall in a new post-Covid era, they are further stacked against their workers. Over the last year 25 different employers have attempted to use the brutal method of ‘fire and rehire’ to lower their workforces pay and conditions. Douwe Egburts issuing dismissal notices against their workers, on strike against pay cuts of up to £12,000 a year, is one example of vicious attempts to undermine pay and conditions under the cover of Covid. Such attacks have not gone unanswered and some of the strikes – like the Manchester Go Ahead bus workers’ action – have been able to force the employers back.

These serious workplace battles are only a taster of what is likely to come in the post-pandemic period. Many employers have delayed attacks on their workforce until further down the road, relying in the meantime on the furlough scheme, business rates relief, the ban on evictions, and other state aid measures. Most of these are currently due to finish at the end of September, which will inevitably lead to a new swathe of redundancies and attacks on pay and conditions. One survey of 2,000 employers by Leeds University reported that almost half of employers had used the furlough scheme to delay “inevitable redundancies” and “cuts in pay or hours”.

The need for the TUC – or if they refuse a ‘coalition of the willing’ – to act to start coordinating the struggle against post-Covid austerity is clear. A massive national demonstration could be a first step in building confidence for strike action. An essential element of the struggle will be to stand in solidarity with those sections of the trade union movement that are first in line for attack, not least the RMT and transport workers. The need to refuse to allow the government’s anti-trade union legislation to stymie action will also be posed.

Nor is it only in the workplaces that struggles are looming. The pandemic has acted to heighten all the underlying tensions in society. Covid has massively increased the levels of anger and alienation among the working-class majority, particularly among the young. The Guardian newspaper interviewed young people from across Europe, Generation Z, about the pandemic. Common threads run through most of their comments, about being a ‘sacrificed generation’, with no job prospects, and a highly uncertain future. In some, personal experience, often combined with the threat of climate change, leads to calls for revolution. Others express fury at the billionaires getting richer while workers lost their jobs. Anger and an openness to socialist ideas is palpable in every single interview.

The Black Lives Matters movement, the Sarah Everard protests and, more recently, the massive demonstrations in solidarity with the Palestinian people, have all been fuelled by what young working-class people suffered over the last year. The surge in evictions that has already begun, continuing to pay through the nose for inadequate higher education which is facing major cuts, and hikes in unemployment, can all trigger mass movements. As regards the latter, the fall in immigration due to the pandemic and post-Brexit has led to some labour shortages, much bemoaned by bosses whose profits have been driven by the super-exploitation of workers from EU countries. However, it is clear that this will not be sufficient to cut across mass youth unemployment and underemployment. According to the House of Commons figures, the youth unemployment rate is currently 13.2% overall but far higher among some sections, with almost 40% of young black people unemployed. This is bound to increase as the furlough ends. Over half a million of those furloughed are under 25. In addition a massive 41.3% of 18-24 year olds are currently economically inactive, mostly in education and without part-time work, the highest since records began in 1992. The role of Youth Fight for Jobs in campaigning for the trade union movement to fight on this issue will be vital in the coming months.

Need for a mass workers’ party

Objectively speaking there is an overwhelming need for a mass workers’ party, capable of bringing together all of the disparate struggles that will develop around a common socialist programme. Labour under Starmer is the antithesis of such a party. However, at this stage, in the wake of the defeat of Corbynism, the Socialist Party and the other forces in the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition are almost alone in the essential fight to provide an electoral voice for the working class.

Unfortunately, the Labour left remains largely bound and gagged as prisoners of the Starmerite Labour machine: even when – like Jeremy Corbyn – they have been kicked out of it! In the wake of May’s elections disaster Labour left figures did not even call for Starmer to go, limiting themselves to vain appeals for him to change direction. When left MP Diane Abbott did dare to raise an alternative leader it was to say she would back the Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, because he is seen as “a neutral figure”! Burnham, unlike Starmer, has at least feinted in the direction of standing up to the government over the lack of financial support for Manchester during last autumn’s Covid restrictions. Although he folded when push came to shove even talking a good fight led to an increase in Labour’s votes. Nonetheless, he is, as Abbott admits, very far from being a representative of the party’s left. When Corbyn resigned Burnham called for a new leader from the party’s “mainstream tradition” by which he clearly meant, at best, less left wing. He has never called for Corbyn’s reinstatement to the parliamentary party.

While left Labour MPs appear to be continuing to hope against hope that ‘something might turn up’ from within Labour, the forces from which a new party will be formed are beginning to coalesce. The Bakers’ Union (BFAWU) have, for example, conducted a survey of their members on their union’s affiliation to Labour. The results are revealing. A small majority – 53% – disagree with continued affiliation to Labour. This is not non-political trade unionism however as 56% wanted to keep a political link. The union’s report notes that their members commented on “the decision by the Labour leadership to blindly follow the Conservatives in its disastrous handling of Covid” and how many “have started to look to smaller independent parties as an alternative to the mainstream ones”. A rule change requires a two thirds majority, and the leadership of the Bakers’ Union are not proposing action based on the report. Nonetheless, it is a clear indication of how workers entering struggle will start to look for their own political voice.

This issue is also posed in Labour’s biggest affiliate, Unite, in the general secretary election currently away. Left candidate Sharon Graham has not made a call for a break with Labour. Nonetheless, her manifesto states that she would “oppose any local authority, including Labour, if they attempt to force through cuts to jobs and services” and also that she favours supporting “candidates who oppose cuts to Unite members’ jobs and services and councils and councillors who fight against them”. Her supporters include many of the most militant stewards in the union, and if she wins the question of standing or supporting candidates outside of Labour in order to achieve her aims will be sharply posed.

Nor will the debate only take place in the affiliated trade unions. The RMT, which has led the way in being the only trade union so far affiliated to TUSC, is facing major industrial battles. The London Transport region is, for example, struggling against a serious attempt to make transport workers and passengers pay for the Covid crisis. Labour London Mayor Sadiq Khan has signed up to the government’s demands that Transport for London should become self-financing by 2023, the only transport system in Europe to be so.

Even before the pandemic achieving that would only have been possible on the basis of cuts to workers’ pay, conditions and pensions, plus fare hikes and regressive road charges. With travellers numbers down post-pandemic it will require huge and savage cuts. Correctly, the RMT is fighting against any cuts or price hikes, while also making clear that the level of service needs to be maintained to allow for social distancing, and that the aim of decarbonising London’s environment can only be achieved via affordable high-quality public transport. Industrial muscle will be vital to winning the coming struggle, but – in this and the national battles of transport workers – the need for a political voice fighting for the same programme is very clear. With the Labour Mayor doing the Tories bidding, and the Greens forming an alliance with the Tories in the London Assembly, there is no road to achieving this via the established parties. The battle for working class political representation is therefore going to be forced by events.