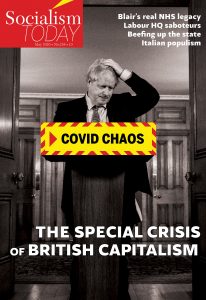

Britain could well end up with the highest Covid death rate in Europe, fuelling the accumulating anger at the government’s handling of the crisis. While the union tops have largely vacated the field and Keir Starmer’s Labour leadership election was a victory for the capitalist establishment, that anger will find an outlet in a society being turned upside down by the crisis. HANNAH SELL writes.

On the surface Britain’s government did not seem the worst prepared for the corona pandemic. Prime minister Boris Johnson had led the Tories to election victory just three months earlier with the biggest parliamentary majority for the Conservative Party since 1987. In 2019 Britain had been found to be the second best prepared for a pandemic of 190 countries, beaten only by the US. As the pandemic has developed, however, while no government has taken the necessary measures to fully defend the working class from its effects, Britain has had one of the most ineffectual responses of the major capitalist powers.

At the time of writing the government’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is predicting a gigantic, unprecedented 35% fall in economic activity in the second quarter of 2020 and has warned of a greater hit to living standards than that caused by the 2008 banking crisis. Two million people have applied for universal credit as a result of becoming unemployed. Meanwhile officially recorded hospital based deaths from the coronavirus have passed 17,000.

It is clear to everyone that the real figure is much higher with thousands of unrecorded deaths in care homes alone. One leading pandemics expert, and member of the government’s scientific advisory group for emergencies (SAGE), Sir Jeremy Farrar, has confirmed that Britain is now on course to suffer the highest number of deaths in Europe. While there is still a long way to go before a full balance sheet can be made, it is clear that British capitalism has performed especially badly.

A history of calculating callousness

Why? A major factor was the government’s initial reaction to the pandemic. On Thursday 12 March Johnson warned that “many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time” in the course of the pandemic. The following day the government’s chief scientific advisor, Sir Patrick Vallance, blurted out the truth, that the government was relying on the development of “herd immunity”, which it estimated would require forty million people catching coronavirus.

An unseemly scramble to retreat from this position then ensued, with the Tories denying that their approach had ever been to stand back and let the virus rip. They were under sufficient pressure that they had to put out an official denial that Johnson’s chief advisor, Dominic Cummings, had ever said that the government’s strategy was “herd immunity, protect the economy, and if that means some pensioners die, too bad”. However, the NHS’s digital planning arm – NHSX – was still using a document on 23 March which included targeted herd immunity as part of the government’s strategy.

In fact, the Tories initial calculating approach has been the norm for British capitalism’s attitude to public health. Many comparisons have been drawn with the 1918 flu pandemic. It killed 228,000 people in Britain. It was never discussed by the British cabinet, and was not even discussed in parliament until the end of October 1918, weeks after the second – and most deadly – wave of the virus had hit the country. It was not made ‘notifiable’ to the authorities until the third wave struck in 1919. Although it was understood that crowds would lead to the spread of the disease, and just like today, official advice urged avoiding crowded public transport and self-isolating if sick, no serious measures were taken. Mass gatherings continued and factories operated freely, the only change being that some relaxed their ‘no smoking’ rules as smoking was believed to keep the flu at bay!

For the capitalist class, whose interests, if not always immediately and directly, the Tories represent, the priority is not the health of the population but that of their system. Where taking no action to counter disease has no negative economic or political consequences for capitalism no action is taken. For example, worldwide between 2010 and 2018 an average of 500,000 people a year died from malaria. It is estimated that it would cost around $90 billion to eradicate malaria globally by 2040, less than 5% of the current stimulus package of the US government alone. Yet while malaria has been eradicated in Europe since around 1950 it remains rampant in the neo-colonial world.

Historically, even when British capitalism has taken decisive steps to improve public health it has only done so belatedly. The 1875 Public Health Act, for example, introduced by Tory prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, followed decades of campaigning for measures to improve the horrendous insanitary conditions in Britain’s industrial centres. The Act, which put a duty on local authorities to build sewerage systems, reflected that the rich could not successfully isolate themselves from cholera and typhoid epidemics, leading the capitalist class to eventually conclude that they had no choice but to take serious measures.

Johnson forced to U-turn

The coronavirus U-turn took not decades of campaigning, but a matter of days. The Johnson government realised they would face mass unrest and could be evicted from office if they maintained their herd immunity strategy while other major economies locked down, with the death toll mounting and the NHS being overwhelmed.

It was clear that the latter was on the cards. ‘Exercise Cygnus’ – a 2016 cross-government pandemic drill – had predicted it. Its conclusions were never made public or acted upon, even though the government’s 2015 ‘national risk register’ had calculated that there was a between one-in-twenty and one-in-two chance of a pandemic hitting Britain in the next five years. Instead it seems that, as part of the austerity drive, stockpiles of personal protective equipment (PPE) designed to cope with a pandemic had been drastically cut back. The value of the stockpile had fallen by 40% between 2013 and 2019.

Although the Tories were forced to change tack the lockdown in Britain is still relatively limited, with manufacturing and construction – for example – still allowed to function. What shutdowns in those sections that have since taken place have mainly been as a result of pressure from the workforce.

Decades of neo-liberalism and ten years of austerity has also left British capitalism with limited options beyond the Tories’ initial herd immunity strategy. Globalisation has left most of the advanced capitalist world short of medicine and protective equipment manufacturing. It is estimated that 80% of PPE is produced in China and every second vaccine dose worldwide is made in India.

The government’s late change of approach left them lagging behind in the global scrap between nation states over PPE, ventilators, tests, and medicines. In addition the particular weakness of UK industry, highlighted by health minister Matt Hancock regarding the lack of diagnostic capacity – although even then there were private company and university facilities that could have been requisitioned – put limits on what could initially be produced domestically.

An even bigger factor is the huge cuts that have taken place in the public sector. At the start of the crisis Britain had just over 4,000 intensive care beds, one of the lowest numbers in Europe. Italy for example had 8,000 and Germany 28,000. Nor is it just intensive care beds. Overall the UK comes 35th in the world league table for the number of hospital beds per thousand people.

Cuts also lie at the root of the dire lack of testing in Britain. Until 2003 the Public Health Laboratory Service provided a network of more than 50 laboratories. New Labour in government dramatically cut that back and centralised as part of its application of neo-liberal policies to public health services (see the article by Jon Dale on page 13 on New Labour’s Real NHS Legacy), resulting in a severe lack of testing facilities. As of April 1 testing in Britain was one of the lowest in Europe, per head, behind Denmark, Germany, Italy and Austria. While on April 4 Germany had carried out over 1.3 million tests, the figure for Britain was only 152,000.

The death rate from the virus will not only be higher in Britain because of the direct effects of austerity on health care but also because of the resulting increased levels of poverty. Deaths from respiratory diseases are three times as high in Britain than the European average, with death rates highest in regions with high levels of poverty – South Wales, Glasgow and Liverpool top the table.

Nonetheless, the lockdown has had some effect in slowing down the spread of the virus. At the time of writing the NHS has not been overwhelmed despite major pressures in some areas. However, the government has no clear idea how to get out of the lockdown prior to the development of a vaccine, and there are clearly cabinet divisions on the question; with no clear chain of command while Johnson continues to convalesce from coronavirus.

Neil Ferguson, the prominent government advisor and epidemiologist, has now broken ranks to say that the road to easing the lockdown is “single-minded emphasis on scaling up testing and contact tracing” and expressing frustration at the government’s failure to move decisively in that direction, comparing the amount of planning done for Brexit to the complete absence of planning for an epidemic.

Accumulating class anger

Despite their abysmal handling of the crisis, at this stage – like many other governments – the Tories have good poll ratings. It would be a big mistake, however, to imagine that this represents deep-rooted or long lasting support.

Comparisons between the fight against the coronavirus and a war have become commonplace. Like is often the case in the early stages of a war, there is a certain mood that it is necessary to back the government now, in order to defeat ‘the enemy’, leaving grievances about its failings until after the virus has been dealt with. At the end of the second world war the accumulated class anger was expressed with the defeat of Churchill and a landslide for Labour. In the future the working class will also make Johnson pay for the widespread suffering the government’s handling of the crisis has caused.

At this stage, however, the capitalist class are conducting an enormous propaganda offensive – again similar to a war – to foster a mood of national unity behind the government. Part of this is a cynical campaign to celebrate the heroes of the NHS, even including a government-funded ‘wraparound’ for every major daily paper calling for people to take part in the weekly clap for NHS workers. It is not lost on NHS workers, however, that – while the Tories are eulogising them now – they have presided over a decade of cuts, privatisation and pay restraint. Even now, in the midst of the crisis, with hospitals running out of PPE for staff, the Health Minister has refused to discuss any prospect of a pay increase for NHS workers.

The lock down will have a profound effect on class consciousness, particularly of the minority of workers who are still physically in the workplace. When the SAGE committee proposed the lock down it estimated that there were five million workers “in essential services and critical infrastructure” who would remain in the workplace. Many of these, such as social care workers, are among the lowest paid sections of the working class. It is now clear – to them and to the public as a whole – that they play a crucial role in running society. This in itself will raise their collective confidence.

In addition countless battles have been waged by these essential workers for adequate PPE and health and safety measures. Some – including refuse, postal and construction workers – have led to walkouts. Others have won victories without having to resort to that. London bus drivers – 26 of whom have so far died from coronavirus – have taken action, with Socialist Party member Moe Manir playing a leading role, to block off the front doors of their buses (where the driver sits and payments are made) so that passengers enter through the middle or rear doors. As a result of this element of workers’ control imposed by the drivers, the Blairite Labour mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has had to accept that all bus journeys will now be free.

There are many other similar examples. At the same time many trade unions have reported an increase in membership as workers – whether based at home or in the workplace – look to the workers’ movement to defend their interests.

However, the tops of the trade union movement and the Labour leadership have not taken the same fighting approach as workers on the frontline. As in war, the capitalist class has attempted to incorporate the leaders of the workers’ movement into their campaign of ‘national unity’ which, in reality, is a campaign not to protect the health of the population but the capitalist system.

While no trade union leaders have formally joined the government, the TUC’s coronavirus statement sums up their approach, calling on the government to “bring together a taskforce of unions and employers to help coordinate the national effort”. Unfortunately, even some left union leaders have succumbed. Mark Serwotka, general secretary of the PCS civil servants’ union, has, for example, proposed “parking” his members’ demands until the corona crisis is over.

Starmer’s win a victory for capitalism

At the same time Keir Starmer, the newly-elected leader of the Labour Party, has made clear his willingness to sustain the Tories in office. That he is prepared to do so is just one indication that his assumption of the leadership represents an important victory in the capitalist class’s campaign to once again make Labour a party that can be relied on to govern in its interests.

Back in 2015, when Jeremy Corbyn was thrust into the leadership of the Labour Party as a result of tens of thousands of people signing up as registered and affiliated supporters to vote for him, the capitalist class feared the possibility of a mass workers’ party with a socialist programme being formed out of the Corbyn surge. Such a development was a real possibility, but it required mobilising those enthused by Corbyn in a determined campaign to democratise and transform the Labour Party – removing the pro-capitalist MPs and councillors that dominated the party then, and unfortunately still today.

As the Socialist Party has consistently warned, the policy which the left leaders of the Labour Party pursued – which was primarily to compromise with the right in the hope of pacifying them – was bound to lead to defeat. Every weakness shown by the Labour left has been met with the aggression of the Labour right, and behind them the capitalist class, who were determined to annihilate Corbynism.

This was summed up by the veteran Blairite Tom Harris, writing in the Telegraph, who defended the contents of the recently-leaked internal party dossier by saying: “The conclusion to be drawn is not that the Labour Party is, as it has always claimed, a broad church of diverse opinions and priorities, but that it is an uneasy alliance of two separate parties, each with separate, diverging and even opposing aims and principles. And each side sees the defeat of the other as a necessary prerequisite to its own success”.

That this was the approach of the pro-capitalist wing of the Labour Party including within the party officialdom is confirmed in every detail by the dossier (see the article by Dave Nellist on page nine, Saboteurs At The Heart Of Labour’s Apparatus). Alongside the foul personal abuse right-wing officials used against individuals on the left, the report describes a systematic campaign from inside the Labour Party HQ aiming to ensure Labour lost the 2017 general election.

On that occasion, although Labour did not win, the huge surge in its vote – the biggest since 1945 as workers were enthused by Corbyn’s anti-austerity programme – strengthened Corbyn’s position despite the right’s sabotage. This was not taken advantage of, however, and the further concessions made to the right wing in the following years, particularly but not only on Brexit, led to defeat in 2019, which the right has now successfully used to regain the leadership position.

It would not have been possible to win with an openly Blairite candidate, and Starmer instead posed as wanting unity, and adopted aspects of Corbyn’s programme. Nonetheless, the reality is revealed by those who backed him, including the two main Blairite groupings in the Labour Party and George Osborne – the man who as Tory chancellor was responsible for the most vicious austerity since the 1930s.

While Starmer could well be prepared to join a national government, it is not the most likely scenario that he will be asked to do so. The Financial Times on 6 April, welcoming Starmer’s election as “offering the prospect of the return of a competent opposition party”, warned him to “resist being drawn into too tightly” to the current government because “while Boris Johnson still maintains support in a national emergency, much of it will be shallow and short-lived”. The capitalist class, unless they can see no alternative, would rather Starmer is not discredited by association with the Tory government, as they can see the possibility of needing him to replace it in the not too distant future.

They are right to worry. The coronavirus crisis is turning the world upside down. The political, social and economic consequences will be profound. In the short term the Tories approach to the lockdown is causing tremendous hardship. Prior to the crisis around a million people a year were using food banks. Since the lockdown started food banks across the country have reported a tripling – or more – of their users, and a lack of sufficient food supplies to meet their needs. Summer riots could be on the agenda with looting for food and essentials being more central than those in 2011.

Desperate economic measures

Panic stricken about the scale of the economic crisis, the British government and the Bank of England – like the governments and central banks of the other major capitalist powers – have ripped up the neo-liberal rule book. They have intervened into the economy on a huge scale. The government pledged over £400 billion to prop up business during the lockdown. The Bank of England pledged to buy £200 billion of UK government bonds to fund this spending spree. This dwarfs the bailouts of 2008 and, unlike them, involve the whole economy rather than just the finance sector.

As always, the capitalist class is prepared to mortgage the future in order to save their system today. The sums they have pledged have prevented, at least for now, a collapse of corporate credit and the resulting bankruptcy of swathes of companies. They hope against hope that they have prevented longer term damage to the economy, enabling a ‘v’ shaped recession, with a recovery as steep as the plunge, taking the economy quickly back to where it began.

Were they to succeed it would be the best outcome for the working class, among whom there will be a widespread search for an alternative to capitalism whatever the immediate post-covid economic situation. The crisis has demonstrated how the capitalists, in order to save their system, will resort to levels of state intervention which they were decrying as ‘unthinkable’ and ‘Marxist’ just weeks before. This, combined with the role of the working class in bearing the major burden of the crisis, will create the possibility of building mass support for socialist ideas. If the economy were to recover relatively quickly it would also increase confidence among workers to take militant action to demand ‘their due’ in wage increases and improved public services.

However, while there is bound to be some ‘bounce back’ when the economy reopens, there are major obstacles to a ‘v’ shaped recession. Some are linked to how long the lockdown will continue for and, even after it has been lifted, whether the population will return to previous levels of eating and socialising in crowded spaces.

The longer the lockdown continues the more lasting damage will be done particularly because of the considerable gap between the government support announced and the reality of what is available. The scheme which allows employers to claim up to 80% of furloughed workers’ wages for example was announced on 20 March but money will only be disbursed by the end of April at the earliest. In the meantime, employers have announced their intention to furlough a quarter of the workforce, around eight million people. As the rapidly growing unemployment figures demonstrate many – particularly smaller – companies may go out of business before furloughing money comes on stream.

This will be increased by the failure to roll out the business loans that have been promised, with at this stage just one in five companies that have applied actually being granted them. All of these problems are a reflection of the weakness of Britain’s state infrastructure, with decades of cuts and privatisation leaving it incapable of dealing with an emergency effectively. Of course, this will be felt most sharply by those workers who lose their jobs, and have to wait many weeks to receive any state assistance.

World context

Aside from the immediate issues there is also the severe underlying weakness of both the British and world economy. A new world recession was on the agenda before the coronavirus hit. In Britain the economy did not grow at all in the last quarter of 2019, and grew less than 1% through the whole year. Manufacturing suffered its sharpest contraction in the last quarter of 2019 in seven years. And it was the worst on record for British retail, with sales falling for the first time since the current series of records began 24 years ago.

Last year the IMF warned that the enormous levels of global debt meant that a recession even half as deep as 2007-08 would lead to 40% of the corporate debt in eight major economies, including Britain, becoming so expensive during a recession that it would be impossible to service, leading to the insolvency of tens of thousands of businesses employing millions of people. Britain is mid-league in those eight major economies, with corporate debt prior to the coronavirus crisis having reached £443 billion, three quarters higher than the post-2007 low point in 2010-11. While the government has pump-primed the economy to get through the immediate crisis, it is unlikely to be enough to rescue companies that were already teetering on the brink, and have now suffered catastrophic falls in sales.

To try and lessen the depth of the coming crisis the government is likely to have to find ways to continue the state intervention it has carried out in the current emergency, and can even be forced to go further. The British capitalists are terrified that, no matter what measures they take, it may be impossible to prevent the development of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. If the government is forced to continue or expand the Keynesian turn they have made in the heat of the crisis it may prevent the capitalists’ worst fears but it will not stop the suffering of millions or overcome the crisis of British capitalism – with its historically low levels of investment and productivity gains. It would certainly not lay the basis for sustained, healthy growth.

Not least because, with a developing world economic downturn, the coronavirus crisis has increased the already spiralling national tensions between the major capitalist powers. Britain, halfway out of an increasingly divided European Union, is particularly vulnerable. This has been a factor in the government’s failure to procure the means to carry out tests and provide PPE during the crisis. The state intervention already carried out in recent weeks is predicted to increase the national deficit for the financial year 2020-21 to 14% of GDP, the biggest ever peacetime deficit. In the future it can exacerbate the special crisis of British capitalism if the world markets judge Britain’s state debts are more unsustainable than others.

In an uncertain world one thing is certain. The capitalist class will seek to make the working class pay for the crisis, just as it did after 2008. This does not mean, necessarily, that they will be able to return to the open austerity of the past, at least in the short term. Take the NHS: having forced local hospitals into deficit over a decade, they wrote off £14 billion of debt at the stroke of a pen. To reverse this in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, or to move to further privatise the NHS, would lead to an uprising. On the contrary, they will be under enormous pressure to increase NHS funding and health workers’ wages.

In her book on the 1918 flu pandemic, Pale Rider, Laura Spinney describes how the flu “fanned the flames that had been smouldering since before the Russian revolutions of 1917” by “highlighting inequality” and “illuminating the injustice of colonialism and sometimes of capitalism too”. The 2020 pandemic took place against the background, not yet of successful revolution, but of worldwide uprisings against inequality and growing capitalist crisis.

While the lockdown has currently limited class struggle the flames of both will be massively fuelled by the coronavirus crisis. In Britain and elsewhere it will create opportunities to build mass workers’ parties, armed with socialist programmes, which will be vital to the successful socialist transformation of society.